Over the last year I’d come across the name Wolfgang Tillmans a number of times. In almost every instance, he was described differently. “One of the most important and distinctive artists to emerge in the 1990s.” “Fashion and magazine photographer.” “Installation artist.” “A documenter of youth.” “Among the most celebrated of contemporary photographers.” “Turner Prize Winner.” “Gay photographer.” “Snapshot portraitist.” “Architectural photographer.” “Punk still-life photographer.”

How was it possible that Tillmans seemed to be something different to everybody who wrote about him? I wasn’t sure if he was a chameleon or a jack-of-all-trades. Having done some research on Tillmans and his work, I’m still not sure.

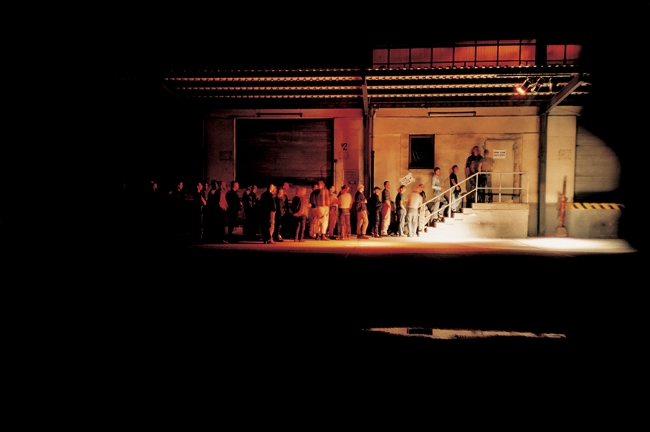

German-born Tillmans first started to garner critical attention in the late 1980s, when he began to photograph his friends at various London dance clubs and raves. His work began to appear regularly in small magazines that celebrated London’s night life and gay culture. It caught the attention of the editors of some London fashion magazines, who found his work to have a relaxed ambience but with a formal compositional style. It didn’t hurt that his photos were directed at a market the fashion industry was eager to reach.

Tillmans’ fashion work led to portrait sessions with musicians and eventually to celebrities. He began to receive offers to show his photographs in small galleries, then in more serious galleries, then galleries in his native Germany and in the United States. Eventually museums began to seek out his work.

How much of this was a result of momentum and how much due to his art or craft is, in my mind, debatable.

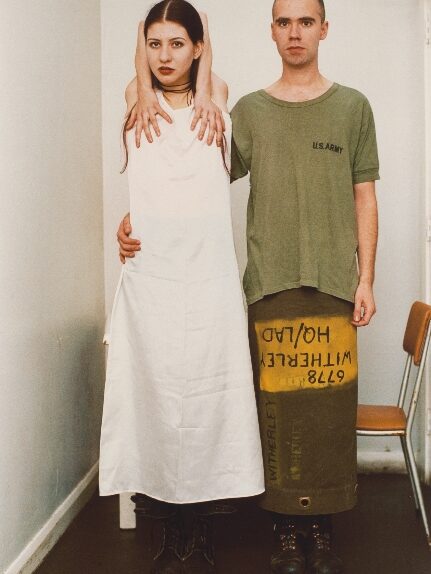

Tillmans’ work has often been compared to that of Nan Goldin, one of the originators of the ‘snapshot aesthetic.’ Like Goldin, his work often depicts the mundane moments and the ordinary scenes of bohemian lives. Unlike Goldin, however, Tillmans also shoots portraits that are studies in imposed casualness. He works with his subjects, who are often his friends (he refers to his portrait subjects as his ‘accomplices’), to compose images that are clearly posed yet retain an air of informality. It’s unclear exactly what role Tillmans takes in their costuming, but the idiosyncratic clothing worn by his ‘accomplices’ is as important as the subjects themselves.

Tillmans says he’s more concerned with the content and context of the work than with the technique. He considers himself an artist first and foremost, rather than a photographer–an artist who happens to frequently use a camera. The result is a tendency on his part to insist that everything he does must be seen through a filter of ‘art.’

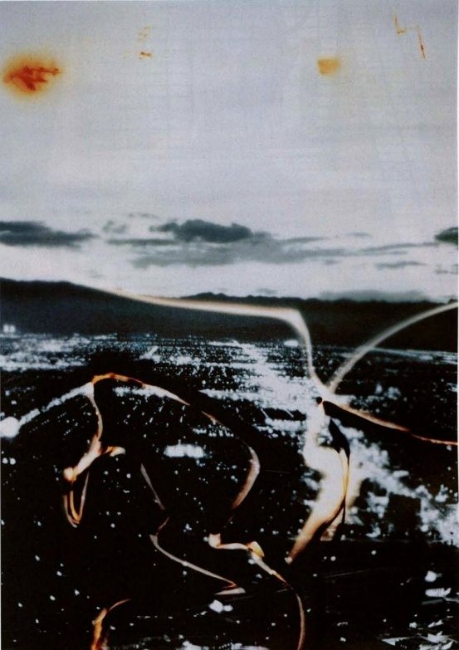

When asked what distinguished his photograph of Las Vegas taken through a scratched airliner window from that of any tourist, Tillmans explained that his photograph was the result of an artistic process.

“In the plane, I have to sit on the non-sunny side. I have to darken the area from where I am photographing, otherwise there will be a reflection on the glass. Then I use a very wide aperture with no depth of field so that the window is not in focus. I must not sit where I’ll be taking pictures into the jet stream, otherwise I get heat striae. When checking in, I name the precise seat number: third row from the back, seat A, for example.”

It’s impossible to say whether that response is merely a pretentious justification for charging a lot of money for a snapshot, or a post hoc explanation for an unexpected result, or a genuine interpretation of his creative process. Regardless, it seems clear that to Tillmans whatever an artist creates is art by definition, and that its irrelevant whether or not the public appreciates it. It’s a very ballsy approach, which I have to respect–grudgingly, at times, but the respect is still there.

Tillmans’ insistence that what matters in his work is the content and context becomes even more clear when it comes to his gallery work. He brings the same sort of defiant, punk-driven aesthetic to the display of his work. He disregards traditional notions of gallery exhibition; he assembles his work in clusters on the wall, clusters that are meaningful to him. Tillmans generally pins or tapes his photographs directly to the gallery wall, unconcerned about the size of the image, the quality of the print, or the material on which its printed. He will pin a professionally printed C print beside an inkjet print beside an image of his taken from a magazine beside one printed on a postcard beside a cheap photocopy of a photograph. He clumps together new images and old images, color images with black-and-white images with swaggering disregard.

This may be Tillmans at his most artistically honest. In his gallery work he is creating–or attempting to create–a sort of narrative. Not a story, but an emotional aggregation intended to work subtly on the viewer’s unconscious. His gallery groupings are intentionally designed to spur the viewer to feel a specific way at a specific time.

Wolfgang Tillmans career may be a product of luck as much as talent. His photographs might, as some have claimed, be over-rated. He may be a pretentious git with a wildly inflated sense of himself. But I suspect that at some point Tillmans work gained a critical mass, at which point the individual elements of his work became less important than the whole. Just as individual stem cells cluster together to form specialized cell types, so Tillmans’ work, when clustered together, must form a specialized sort of artistic communication.

I’m not sure if Tillmans was an artist at the beginning of his career; I believe he is one now. I’m not sure if his photographs, taken in isolation, are art; I believe that his photographs, when viewed as a body, probably is art. It’s entirely possible that Wolfgang Tillmans willed himself to be an artist.