Sometimes the accident of birth shapes the course of one’s life. It’s true for Shomei Tomatsu. He was born and raised in the industrial city of Nagoya, Japan in 1930. The fact that Nagoya was an industrial center became important 15 years later when U.S. B-29 bombers began to firebomb the cities of Japan. Forty percent of Nagoya was destroyed by incendiary bombs.

Too young to be drafted into military service but old enough to understand what was happening, Tomatsu’s worldview was shaped by the war–by the bombing, by the destruction, by Japan’s eventual surrender and the resulting occupation. He not only saw his nation destroyed, defeated, and occupied by a foreign army, he saw his cultural heritage become diminished and devalued. The artists and free-thinkers of his post-war generation scorned the rigid, militaristic, fiercely proud social values of pre-war Japan–but they also scorned the values of their American occupiers. Tomatsu has said his contemporaries “believed in nothing.” They distrusted the past and had no confidence in the future because they’d seen the present incinerated at 5000 degrees centigrade.

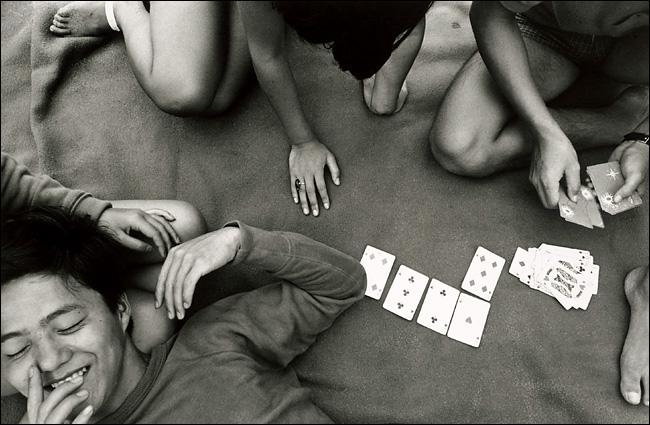

Tomatsu’s generation adopted what they wanted from their own past and from the culture of the occupying army without any regard for tradition. They played cards and go with equal passion and disdain, they drank American whiskey and sake, they ate Spam and sashimi. They lived in a world of caprice and contradiction, a surreal anchorless world.

When Tomatsu began to take photographs in the early 1950s, Japan wasn’t so much being rebuilt as it was being reconfigured. The old Japan wasn’t being reconstructed; a new Japan was being fabricated. In that environment, Tomatsu did what all new self-taught photographers tend to do: he photographed everything, the world all around him. He entered a few photos in a contest and caught the eye of the professional photographers who were the judges. With their encouragement, by the mid-1950s Tomatsu was freelancing for a couple magazines that were the Japanese equivalents of Look and Life.

In 1960 Tomatsu was commissioned by the Japan Council Against Hydrogen and Atomic Bombs to document the aftermath of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The photographs he took in this period remain his best known work. Tomatsu didn’t take a documentary approach; he took an artistic approach. The photos of objects–a cracked wristwatch stopped at 11:02 (the time the bomb detonated), for example, or a beer bottle melted by the heat so that it resembles some weird David Lynch mutant, or a soldier’s helmet with the top of the soldier’s skull fused to the metal–are shot as still life images rather than as forensic evidence of the horror of war. The photographs of survivors are shot as portraits rather than as medical documentation.

Beginning in 1958 Tomatsu spent about fifteen years visiting many of the approximately 90 U.S. military bases in Japan, from Misawa airfield in the north to the bases on the island of Okinawa to the south. Although he did occasionally photograph the GIs stationed there, he concentrated on the shanty towns that surrounded the bases…the bars and brothels, the pawnshops and prostitutes.

Tomatsu was intrigued by the bizarre fusion of Japanese and American cultures that existed in these interstitial communities. Japanese beatnik poets zoomed on motor-scooters through streets filled with mixed-race children, where prostitutes clad in traditional kimono shared the sidewalks with Japanese women wearing American-style beehive hairdos. In a way, the same force that fused the soldier’s skull to his helmet also fused the new Japanese rootless anomie with American arrogance and optimism.

Although revered in his homeland, Shomei Tomatsu’s work remained relatively unknown outside of Japan until recently. Part of that was likely a result of Tomatsu’s refusal to travel outside of Japan. It was also certainly a result of his refusal to focus his work in any traditional category. He is not a portraitist, he’s not a documentary photographer, he’s not an fine arts photographer, he’s not a street photographer, he’s not a surrealist, he’s not a landscape photographer. And yet he has created work in all those areas.

Tomatsu is a déraciné photographer–a photographer not so much without roots as one who has been uprooted. Like so many survivors of the brutality of war, Tomatsu became a scavenger. He searched out what was usable and beautiful among the detritus and confusion, and he photographed it.

Even though it was long over, the war always echoed through Tomatsu’s photography. His black and white photographs of flood damage show the rubbish of everyday life trapped in an almost silvery mud–boots, bottles, gloves–and they look like the aftermath of a battle. A color photograph taken at the Japan World Exposition in 1970 looks like blood spattered on a window. A simple photograph of a cloud over the ocean, the horizon line crazily askant, is reminiscent of the mushroom clouds that rose over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But even though the Second World War resonates throughout his work, Tomatsu’s photographs retain a surreal beauty. An otherworldly beauty. That is his great gift, I think. One of Tomatsu’s contemporaries described him as one of “those who know more than they care to about things they cannot afford to believe in.” Against all the many reasons not to believe, it seems Shomei Tomatsu still believes in beauty.