If the 1960s could be said to have a birthplace, it would have to be London. Probably Carnaby Street. Or maybe the opening of the boutiques on King’s Road. But definitely London. Everything changed. Music, fashion, theater, literature, politics. Entire world views shifted radically. And right in the middle of it all was Lewis Morley, photographer.

You could call it perfect timing. Morley called it luck. That he was there at all is a case of the wildest serendipity. Morley was born in Hong Kong in 1925; his father was English, his mother Chinese. in 1941, when Morley was sixteen years old, the Imperial Japanese Army attacked Hong Kong (only eight hours after the Imperial Navy bombed Pearl Harbor). Young Morley and his parents were interned along with some 2800 others in the Stanley Internment Camp for the next four years. While in the camp Morley somehow came into possession of a Brownie box camera. Needless to say, obtaining or processing film was virtually impossible, so the camera was essentially just an interesting toy. But what child doesn’t love an interesting toy?

At the end of the war, Morley’s family was repatriated to England. As an English citizen in post-war England, he was required to complete two years of compulsory service. Morley joined the Royal Air Force because “I look better in grey.” During his military service, he bought an Exacta 35mm camera and began to take snapshots. When his enlistment was up, Morley enrolled in commercial design courses at Twickenham Art School. His interest: painting.

Painting is a grand mode for self-expression, but it’s a difficult way to make a living. Photography might be marginally easier, so Morley picked up his camera again. He began shooting freelance photographs for a variety of magazines, including Tatler, Go! and Private Eye. This led to a fairly steady gig shooting publicity photographs for various London theaters.

It was through his work for Private Eye that Morley became friends with the comedian Peter Cook. Cook owned a popular cutting edge nightclub called The Establishment, located on Greek Street, Soho. In 1961 Morley leased a studio space above the nightclub. Over the next couple of years the ‘Sixties’ grew around that club and that studio, rather like a pearl forms around an irritating bit of grit in an oyster.

It was the perfect arrangement for a photographer. The nightclub was frequented by the famous and, more importantly, by the soon-to-be famous, many of whom wanted to have their photograph taken. He photographed then-fringe actors like Anthony Hopkins, Michael Caine, John Hurt, Judi Dench and Maggie Smith. He photographed aspiring models like Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy. He was one of the first photographers to document the rising fame of the Beatles. He photographed most of the British pop stars of the era.

Morley always seemed to accidentally be at the right spot at the right time. In 1963 John Profumo, the British Minister of War, was discovered to have had an affair with a showgirl named Christine Keeler. That was scandalous enough, but Keeler had coincidentally also had an affair with one Yevgeny Ivanov, a Soviet naval attache and suspected spy. Sex and politics is always a heady mix for the public. Even as the scandal was unfolding, a London film company saw the potential for a movie. Because of his work with actors and film studios, Morley was asked to shoot some publicity stills for the planned film. His model? Christine Keeler herself.

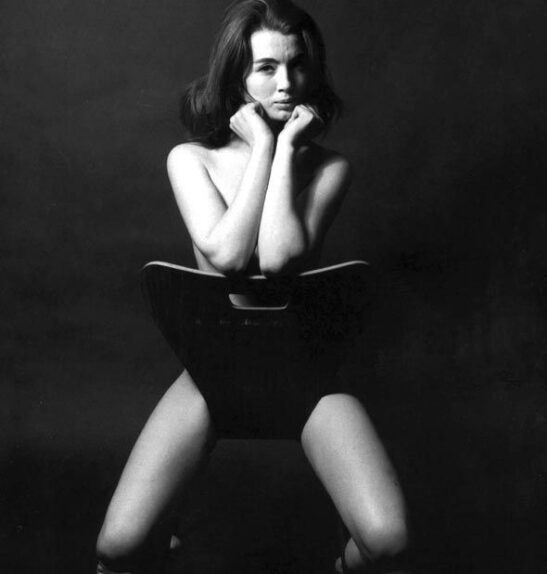

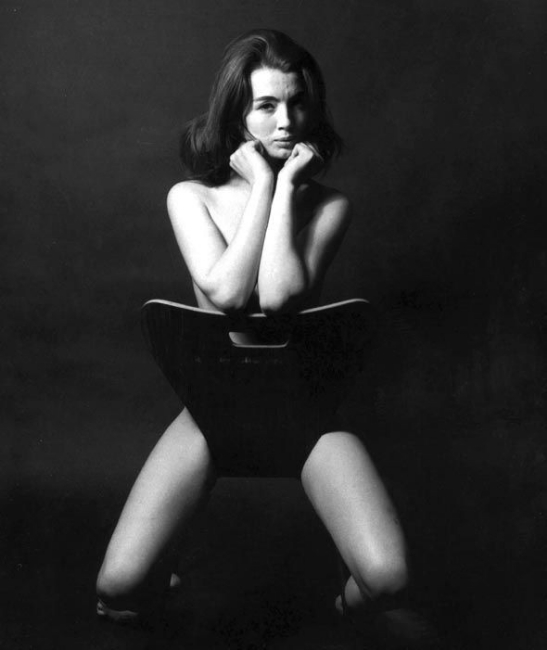

The movie was never made, but one of the photographs of Keeler became one of the iconic images of the 1960s. In his studio over the nightclub, Morley photographed Keeler with a single prop–a faux Arne Jacobson ‘Ant’ chair. He shot two rolls of twelve exposure 120 film of her sitting on or near the chair. At the end of the second roll, the film producers insisted Keeler pose in the nude.

“Christine was reluctant to do so, but the producers insisted, saying that it was written in her contract. The situation became rather tense and reached an impasse. I suggested that everyone, including my assistant leave the studio.”

Once they were alone, Morley quickly shot the last roll. To make her more comfortable, he had her sit on the chair backwards. This fulfilled the conditions of the contract, but allowed her remain largely hidden. After only five minutes and ten exposures, Morley was ready to stop. “I felt that I had had shot enough and took a couple of paces back. Looking up I saw what appeared to be a perfect positioning. I released the shutter one more time…it was the last exposure on the roll of film.”

Since the movie was never made, that photograph might never have been seen. The negatives for that photo session would likely have remained in Morley’s files. But somebody from the production company (it was never determined who) copied the negative and either sold or gave it to the Sunday Mirror. The tabloid published the photograph without Morley’s permission, bringing the scandal to new heights and a strange sort of fame to Morley. The image has since become one of the most copied poses in photographic history.

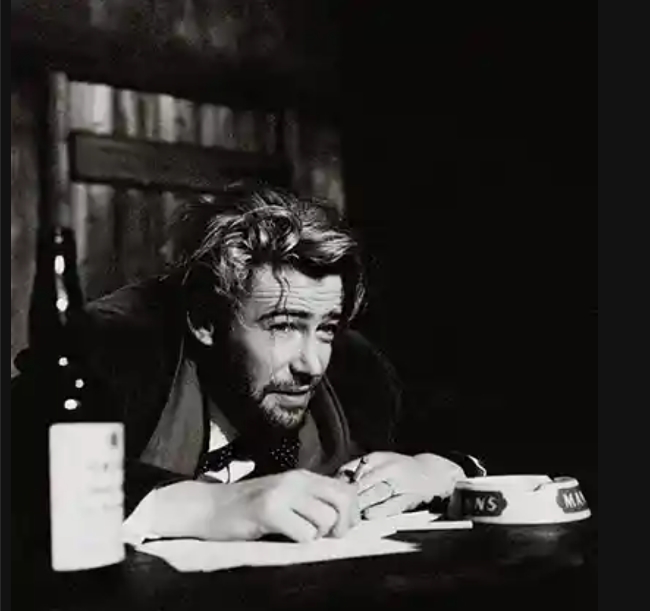

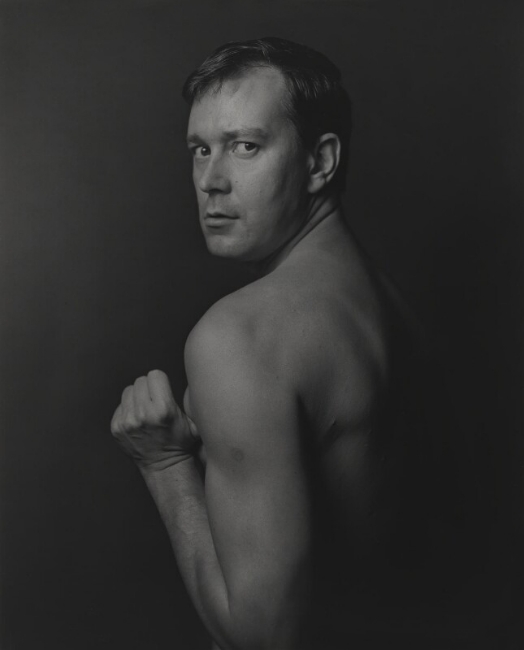

“Plum assignments just kept falling into my lap,” Morley told one interviewer. One such assignment was a portrait session for a rising star in the London theater world, Joe Orton. Orton wrote outrageous plays in which the characters committed the most heinous sorts of behavior, all the while engaging in meaningless, polite, bourgeois conversation. Because many of his characters were openly gay–still rather shocking in the early 1960s–Orton is seen as a pioneer of the contemporary queer literary movement.

A straight man photographing an openly gay playwright in the nude–it was considered shocking. Not long after the portrait session with Morley was finished, and just as Orton’s career began expand from London to Broadway and the movies (he’d just finished writing a screenplay for the Beatles), he was bludgeoned to death by his lover, Ken Halliwell, who then committed suicide. In 1987 Orton’s life and death were turned into a movie, Prick Up Your Ears, starring Gary Oldman.

In the same way he arrived in London shortly before the birth of the 60s, Morley left shortly before the era’s death. For reasons I’ve been unable to discover, in 1971 Morley (and his wife and child) emigrated to Australia. He has lived there ever since. He had no trouble finding photographic gigs; he continued to shoot casual celebrity portraits, but also began to quietly amass a large body of work in food photography for magazines.

He ‘retired’ in 1987, though he has cooperated with several retrospectives of his work in various galleries and museums in England and Australia.

“People talk about you being a great photographer and I sort of feel guilty. I really do. Because things happen to me. It has been like this all my life. I’m not trying to be modest, I’m an awful photographer. Seriously, I’m hopeless technically. But I improvise and that’s why I became used a lot by young art directors in the ’60s…I’m like an early jazz player who can’t read music. I have no sort of actual technical knowledge but I improvise. And that’s my photography: improvisation all the time.”

The 1960s unzipped Western culture–opened it right up, emptied out a lot of stale and musty bits, added a lot of exciting and colorful (and occasionally dangerous) new bits, and still not satisfied, turned the entire thing on its head. It began in a small, localized nexus of maybe twenty blocks in London. And there in the middle of it all was a half-Chinese internment camp survivor with a camera, improvising as the world changed around him. There’s only one way to describe that.

Groovy.