Don Hong-Oai was born in 1929 in the city of Guangzhou in the Guangdong Province of China. He is often described as a Chinese artist, but not because of where he was born. He left China at the age of seven, after the sudden death of his parents. As the youngest of 24 siblings and half-siblings, Don was sent off to live in a Chinese community in Saigon, Vietnam. Later in his life he would occasionally return to visit China, but he never lived there again.

On his arrival in Saigon, Don was apprenticed to a photography studio run by ethnically Chinese immigrants. There he learned the fundamentals of photography. He also developed an affection for landscape photography, which he practiced on his time off using one of the studio’s cameras. Don remained an apprentice for a decade, after which he worked a series of odd jobs. Although he was desperately poor, he managed to save US$48 to buy his first camera. In 1950, at the age of 21, he began studying at the Vietnam National Art University.

After graduating, Don worked a variety of jobs, but continued to practice photography. He remained in Vietnam through both the First IndoChina War (1946-1954) and the Second IndoChina War (1955-1975, including what we in the US call the Vietnam War). In 1974, near the end of the war, Don accepted a position with one of his former teachers who’d moved to France. Unfortunately, the gentleman died soon thereafter. From France, Don traveled to Malaysia where he worked briefly as a photographer for the Red Cross.

With the war over, Don returned to Vietnam. However, in 1979 a bloody border war broke out between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the People’s Republic of China. The Vietnamese government instituted a series of repressive policies that targeted ethnic Chinese living in the country. As a result of those policies, Don became one of the millions of “boat people” who fled Vietnam in the late 1970s and early 80s.

At the age of 50, speaking no English and not knowing anybody living in the U.S., Don arrived in San Francisco. With the help of the local Chinese-American community he managed to find a place to live and employment. He was even able to set up a small darkroom. By selling prints of his photographs at local street fairs, Don was able to make enough money to return to China periodically to shoot photographs. Most importantly, he was given the opportunity to study for a period of time under the tutelage of Long Chin-San in Taiwan.

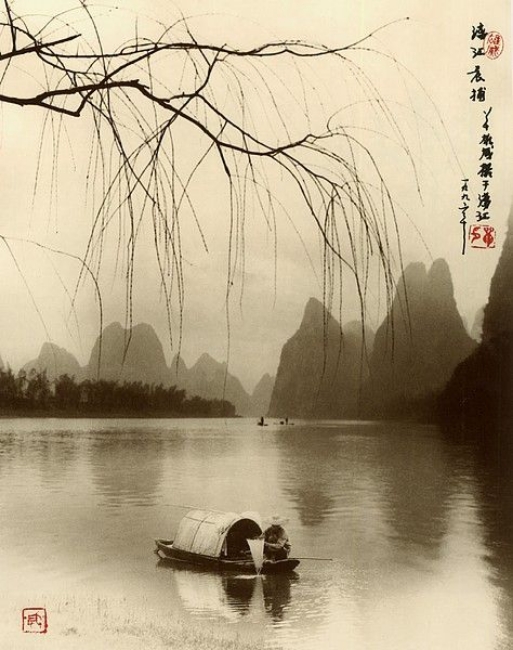

Long Chin-San, who died in 1995 at the age of 104, had developed a style of photography based on the long tradition of landscape imagery in Chinese art. For centuries Chinese artists had been creating dramatic monochromatic landscapes using simple brushes and ink. These paintings weren’t intended to accurately depict nature, but to interpret nature’s emotional impact. During the later years of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 C.E.) and the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368 C.E.) artists began to combine three different art forms–poetry, calligraphy and painting–on the same canvas. It was thought that this synthesis of forms allowed the artist to more fully express himself.

Although there are many variations on that traditional style, such paintings commonly included a human figure engaged in some commonplace activity against a background of natural beauty. To provide a sense of scale and scope, the paintings usually had three distinct layers–a foreground, a middle range, and a distant background. The human figure was, of course, always in the foreground or middle range. The distant background was often blurry or misty.

Long Chin-San, who was born in 1891, had been trained in this classical tradition of painting. At some point in his long career, Long began to experiment in ways to translate that impressionistic style of art into photography. In keeping with the layered approach to scale, he developed a method of layering negatives to correspond with the three tiers of distance. Long taught his method to Don. Don, seeking to more closely emulate the traditional Chinese style, added calligraphy and his seal to the image.

Central to Don’s new work–and central to the technique taught to him by Long Chin-San, which was based the classical tradition–were the six principles of landscape painting first laid out in the 6th century by Xie He (also known as Hsieh Ho). The first and most important principle is that of spiritual resonance, the ability of the artist to feel the true nature of what is being painted–the humanness of humans, the treeness of trees, the waterness of water. This is the only aspect of the six principles that can’t be taught; the other five deal with technique and approach: the correct method of using the brush (or other medium) to achieve the desired effect, fidelity in the depiction of the nature of the subject matter, care in the application of tone and layer, care in placing the compositional elements, and proper respect to the experiences of past masters through reprising themes.

Don’s new work modeled on the ancient style began to draw critical attention in the 1990s. He no longer had to sell his photography from small stalls in street fairs; he was now represented by an agent and his work was being sold in galleries in the US, in Europe, and in Asia. He no longer had to rely on individual customers to buy his photographs; his work was not only being sought after by private art collectors but also by corporate buyers and museums. He was in his 60s and for the first time in his life he was achieving some level of financial success.

Not all of Don’s later work involved the layered negative technique he learned from Long Chin-San, but he remained focused on the spirit of Chinese art. In the last years of his life Don Hong-Oai spent more time making prints in his darkroom in San Francisco’s Chinatown than he did shooting photographs.

He died in 2004 at the respectable age of 75. His remains were cremated; there was no memorial service.

There is a sort of poetic rhythm and justice to the course of Don Hong-Oai’s life and career. He was forced to leave China by tragedy–the death of his parents. He grew up more Vietnamese than Chinese, but was forced to leave Vietnam because of his ethnicity. In the U.S. he was able to survive because of his ethnicity–because he was taken in and nurtured by the Chinese-American community. When Don began to refocus his work on his Chinese roots, he was taken under the wing of a master who had attained a marvelous age. This master taught him an old photographic technique based on ancient Chinese principles. And by applying those techniques, Don attained a level of success he hadn’t imagined possible.

The life of Don Hong-Oai sounds more like legend than reality. That’s appropriate, I suppose, for a photographer whose work seems grounded as much in myth and tradition as in the material world.