We’ve just finished Fashion Week in New York City—the event at which designers and fashion houses introduce their latest collections. It seems appropriate, then, to look at the life and work of one of the most influential modern fashion photographers—Juergen Teller. His story is, in many ways, unremarkable. It may be that what distinguished Teller from any of tens of thousands of other talented photographers is that he was at the right place at the right time with the right aesthetic. Then again, perhaps that’s exactly what makes his unremarkable story remarkable.

Juergen Teller came to photography sideways. He was born in Erlangen, Germany in 1964. For three generations his father’s family had been musical artisans; they crafted components for stringed instruments—mainly bridges for violins. It was taken for granted that Teller would also follow the family tradition; he was entered into a three-year apprenticeship to become a maker of bows for violins, cellos, bass fiddles. Teller was not excited by the prospect. He didn’t know what he wanted to be, but he was fairly sure it wasn’t a bow-maker.

It was his good luck, then, to develop an allergy to one of the components used in the construction of a bow, a condition he now believes was psychosomatic. He became severely asthmatic and had to withdraw from the apprenticeship. While recuperating Teller went camping with his cousin, an amateur photographer.

“Every night I’d be stomping around trying to put up the tent, and Helmut would be sitting quietly, waiting for the sunset. It was so bloody boring until one night, just for something to do, I looked though the camera. That was it. I decided there and then, on a hilltop in Tuscany, to be a photographer.”

Because his medical condition prevented him from finishing his apprenticeship, the German health system paid for Teller to attend college. He chose to enroll in a two-year photography program at the Bayerische Staatslehranstalt für Photographie in Munich. His coursework required lessons in various photographic formats, so the German government bought him three cameras: a 35mm rangefinder, a Hasselblad, and a large format camera. Teller graduated from the program in 1986. At that point he was expected to enter into National Service. “I would have had to work in an elderly home for a year and a half or something,” Teller said. “I thought I’d have to give up photography at 22. so I just said to my mom, ‘I’m leaving’…and then I just drove off to London.“

He had little money, spoke no English, and knew relatively few people in England. Yet he assumed he’d be able to support himself through photography. Teller sold two of the cameras the government had provided him (he kept the 35mm) and lived off the proceeds while he looked for work. He approached fashion photographer Nick Knight, looking for a job as an assistant. Knight encouraged him, but turned him away. Teller then approached a few of the ‘lifestyle’ magazines, like I-D and The Face, seeking freelance work. He convinced them to let him shoot the occasional portrait or obscure musical group.

“I couldn’t even use normal film because it was too expensive to process. I started shooting 35mm Polaroid film which came in twelve and thirty-six exposures. I could only afford the twelve exposures, so for each job I had twelve pictures.”

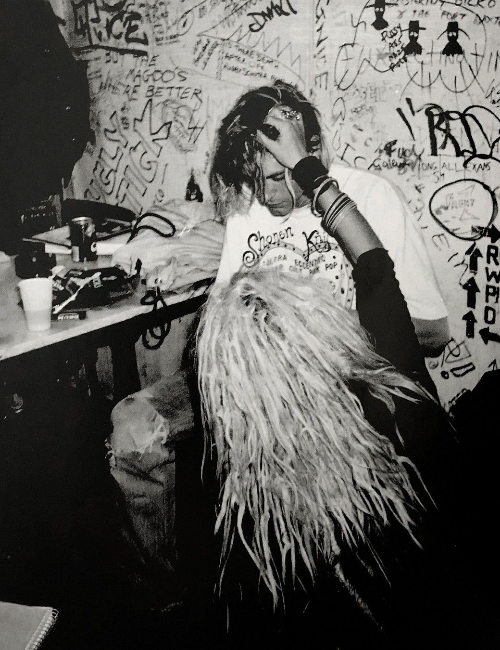

His work had a deliberate lack of glamour that appealed to the alternative musical scene of the late 1980s. He developed a reputation as a “grunge” photographer, a reputation that was sealed in 1991 when he was asked to accompany an American band called Nirvana on tour in Europe. He’d never heard of them, but accepted the gig because it meant a free trip back to Germany, where he could visit his mother.

Not long afterwards, the editors of The Face asked him if he’d like to try his hand at a fashion shoot. Fashion photography was already undergoing a radical shift in approach. Originally fashion photography had been about glamorous photographs of glamorous women wearing glamorous couture clothes. By the time Teller arrived in London, photographers like Patrick Demarchelier, Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin were already in the process of reshaping the industry, making fashion photography more about the glamour of the photography than about the glamour of the clothes. Teller took fashion photography a step farther; he removed the glamour itself.

Teller’s approach to fashion was essentially the same as his approach to portraiture or event photography: relatively little planning, a heavy reliance on improvisation, a casual disregard for tradition, and a willing acceptance of the imperfection of the human body. He used a simple 35mm rangerfinder camera with a flash attached, had only one assistant, and no make-up or styling crew (he apparently continues to work the same way today). He preferred to photograph friends rather than models, but when models were called for Teller generally avoided classic beauties. He tied his early career in fashion to a young model who was considered “impossibly short and quirky” to be fashionable: Kate Moss. “We were kind of free-spirited and hippie-ish and kind of dreamy,” Teller said. “It was a bit scary for the Vogue people.”

Other fashion photographers began to emulate Teller’s deliberately unglamorous approach. The style, pushed to its extreme, eventually became known as ‘heroin chic.’ The description isn’t entirely fair to Teller, but it must be admitted that fashion photography’s plunge into the darker depths of humanity can be traced directly to him.

Certain designers and photographers seem to develop an affinity for each other. Versace and Richard Avedon, Yves Saint Laurent and Helmut Newton, Ralph Lauren and Bruce Weber. The photographers seem to understand how the designers want their brand to be portrayed. For Juergen Teller, the designer he is most closely associated with is Marc Jacobs.

The Teller-Jacobs collaboration began before Marc Jacobs became famous. There was no Jacobs ‘brand’ to maintain or support, no advertising style to follow (or, in Teller’s case, to subvert), no tradition or history. In addition, because Jacobs was relatively unknown at the time, there was almost no money. Jacobs was young enough and confident (or foolish) enough to give Teller free rein over the photography. “It’s really…simple,” Jacobs told an interviewer. “I leave him alone, and he goes off and does his thing. Then we look at the pictures and we talk.” Over the years this collaborative process has resulted in a series of ads that have consistently turned beauty, celebrity, and fashion on its head.

Perhaps the best example of the Teller-Jacobs collaboration took place in 2004. It demonstrates both Teller’s approach to fashion photography (and photography in general) and Jacobs’ approach to fashion advertising. He had just finished a disastrous shoot featuring a famous French actress—a woman accustomed to being made to look young and alluring. When she saw Teller’s photos, she became angry. Teller described the incident to an interviewer: “She said, ‘You make me ten years older than I am,’ and I said, ‘You think you’re ten years younger than you are.’ And then she sort of kicked me out of her apartment.“

Not long afterwards, Teller and his wife had a meal with the actress Charlotte Rampling, with whom he’d developed a friendship. They discussed how women deal with aging, and notions of beauty, and how it felt for an ‘older woman’ to be photographed (Rampling was nearly 60). In the end Teller came to a conclusion. “I realized I needed to photograph someone who doesn’t care at all how they look. So that, of course, can only be one person—me. In the end, the only person I can be as brutally honest as possible with is me.” Actually, in the end, the people Teller could trust included Charlotte Rampling.

The three of them—Teller, his wife, and Rampling—took the lavish Louis XV suite in Paris’s Hôtel de Crillon. Teller brought the clothing samples Jacobs had provided for the earlier shoot with the actress. As always, Teller had only the vaguest idea of what he wanted to do with the shoot: he and Rampling would wear the clothes, get into the suite’s opulent bed, and see what happened. Unfortunately, Teller was too fat to fit into any of the clothes except for a pair of silver running shorts.

After Rampling stopped laughing, she asked Teller what he wanted to do. “And I said, ‘Well, I don’t know. But really, honestly’—and I could hardly bring it out of my mouth—I said, ‘I just want to kiss you and fondle your breasts.’ And she didn’t say a word. She just leaned back in her armchair and went into her handbag and got a cigarillo out…and I was mortified. And then she sort of dragged on her cigarette and said, ‘Okay. Let’s start. I’ll tell you when to stop.’”

The resulting ad campaign (for much of which Teller was nude) was unlike anything that had ever been seen in fashion photography. “For me it was important than [a 60 year old] woman is in a high-class fashion ad, or whatever you call it, and a 40-year-old overweight guy, instead of these anorexic kids,” Teller has said of the ad series. Others have agreed. One fashion critic said, “It’s almost as if, by placing himself in the photographs looking naked, pudgy, and often sad, [Teller] has removed the sadism inherent in so much fashion photography.”

Teller has done other unconventional work with conventional stars and celebrities. He seems almost unwilling to capitalize on their celebrity status. A photo shoot with Sofia Coppola in New York City’s Central Park resulted in an advert showing only her hands holding out a Marc Jacobs handbag toward a curious squirrel. He recently photographed himself with art photographer Cindy Sherman, looking like strange, androgynous twins in Marc Jacobs sweaters. With Victoria Beckham—one of the most photographed women in the world—Teller shows only her legs emerging from a giant Marc Jacobs shopping bag.

In this rather unconventional way—by removing the celebrity from the frame—Teller is returning the product to fashion photography. The Sofia Coppola handbag advert may not be entirely about the Marc Jacobs bag, but it surely isn’t about Sofia Coppola. The Victoria Beckham advert essentially asserts that celebrities are, themselves, a product—a commodity.

Although his work has helped reshape fashion photography, Teller hasn’t in any way altered the mechanism of fashion. Charlotte Rampling at 60 in a suite in a Parisian hotel, Cindy Sherman in a striped sweater, the singer Bjork eating a plate of spaghetti nero all share one commonality with the thinnest and most beautiful 19 year old posing in the most expensive gown in the glossiest of fashion advertisements: they represent something unattainable by ordinary people. The difference is, with Juergen Teller’s photography the unattainable doesn’t look unattainable.