He’s generally described as the greatest—or one of the greatest—of all British photographers. That’s a lot of weight for a person to carry around.

There’s always an inherent risk in writing about ‘the greatest’ in any field, including photography. Critics, admirers, other photographers—all sorts of people often have an emotional investment in ‘the greatest.’ It becomes so easy to offend somebody’s sensibilities and spark an argument. But the real problem in writing about the truly great photographers is that they aren’t easily contained in a single short essay.

It’s not just Brandt; I’ve felt the same way when it came to writing about any photographer described as ‘the greatest.’ I was reluctant to write about Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank and a few others who are described as being among the great.

One reason Brandt, for example, is considered to be among the great is because he’s famous for his landscapes. And for his portraiture. And for his photographs of British society. And for his images of ordinary folks during the Second World War. And for his nudes. Each of those facets of his work deserves to be examined and discussed—and yet it’s impossible to do that adequately in an essay of this length. It’s doubly impossible to do that AND to give the background necessary to understand Brandt as a person as well as understanding him as a photographer.

So—what to do? What I’ve chosen to do is focus this salon on the material I like best: Brandt’s early photographs of British society and his later portraits. His landscapes, his nudes, his photojournalism during the war—they’re all worthy of study, and I advise everybody to seek out those bodies of work. At some point in the future I may even return to them in another Sunday Salon. But for now I’m going to focus on Bill Brandt’s people, the portraits (both formal and informal) of the men and women who lived in the land Brandt loved.

Those photographs are exemplified, I think, in the very first Bill Brandt photograph I can recall seeing—a photo of a girl doing the Lambeth Walk.

There’s such a wonderful combination of innocence and awareness in that photo, such a contradiction between the joyful strut and the bleak setting. It’s an image that, once seen, takes up residence in the memory and lives there. The photograph is imbued with such a deep sense of time and place—England between the wars—that it might as well have a Union Jack stamped on it.

And yet one of the peculiarities of Bill Brandt (and there were many) is that even though he’s usually described as one of the best British photographers, he wasn’t born in Britain. He was born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg, Germany in 1904. His mother was German, his father was a British citizen who’d lived in Germany since the age of five. Young Willy (as he was called then) grew up more German than British.

His family was relatively wealthy and he had a privileged childhood. But despite the family’s social standing, Brandt’s father (as a citizen of a nation with which Germany was at war) was interned for six months during World War I. For the most part, though, it appears the war had less impact on the Brandt family than on most Germans. Willy attended a school for the elite families of Hamburg, but did poorly as a student.

When he was fifteen, his father, believing the boy was simply lazy, packed him off to a boarding school in Elmshorn in Prussia. The war had recently ended and many Germans were angry and resentful. Not surprisingly, Brandt’s British citizenship became an issue. Even though he’d never set foot in England, Brandt was sneered at by some of the teachers and bullied by the other students. According to Paul Delany, “There is ample evidence that Brandt suffered a psychic wound in his school days, something so hurtful that it affected every area of his life afterwards.” Whatever that wound was, Brandt never spoke about it. In fact, after he eventually established himself in England, Brandt would go to great lengths to deny his German heritage.

His studies at Elmshorn were periodically interrupted by illness. Brandt, like many Europeans after the war, suffered from tuberculosis (the rate of TB doubled during the last years of the war). He spent a great deal of time in a Swiss sanatorium, where he became interested in photography (the facility had a darkroom). That interest continued after Brandt was sent to Vienna to undergo an experimental form of psychoanalytic treatment for tuberculosis (a person could do an entire essay on this facet of Brandt’s life). In Vienna he met the poet Ezra Pound, who later introduced him Man Ray in Paris. In 1928 Brandt bought one of the newly-introduced Rolleiflex cameras. One year later, he was working as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio. Two years later, Brandt emigrated to England.

Although he did occasional work for the News Chronicle, and for Verve and Weekly Illustrated magazines, Brandt primarily relied on his family contacts to gain access to subjects he wanted to photograph. Class-conscious England between the wars could be a playground for a photographer with money and access.

“I started by photographing London–the West End, the suburbs, the slums. I photographed everything that went on inside the large houses of wealthy families, the servants in the kitchen, formidable parlourmaids laying elaborate dinner tables, and preparing baths for the family; cocktail-parties in the garden and guests talking and playing bridge in the drawing rooms: a working-class family’s home, with several children asleep in one bed, and the mother knitting in a comer of the room. I photographed pubs, common lodging-houses at night, theatres, Turkish baths, prisons and people in their bedrooms.”

Many of those photographs were published as a book: The English at Home (1936). Two years later, his second book was released: A Night in London, which was inspired by Brassaï’s Paris de Nuit. Unlike Brassaï, though, Brandt provided his own lighting, setting up complicated arrangements of portable tungsten floodlamps. He claimed he owned enough electrical cable to run the length of Salisbury Cathedral.

Everything changed in 1939—for Brandt, for all Londoners, for all the British and all the Europeans and, eventually, for the entire world. That was the year the Second World War began—the year Londoners learned the term ‘blackout.’ His study of London during the blackout and the Blitz made Brandt famous—and rightly so. It’s a terrific example of photojournalism. The images he made during this period are fascinating and important as historical documents. As noted earlier, though, this salon is focused on Brandt’s non-journalistic photography.

After the war, Brandt’s photographic style shifted. “I think I gradually lost my enthusiasm for reportage,” he wrote. “My main theme of the past few years had disappeared; England was no longer a country of marked social contrast. Whatever the reason, the poetic trend of photography, which had already excited me in my early Paris days, began to fascinate me again.”

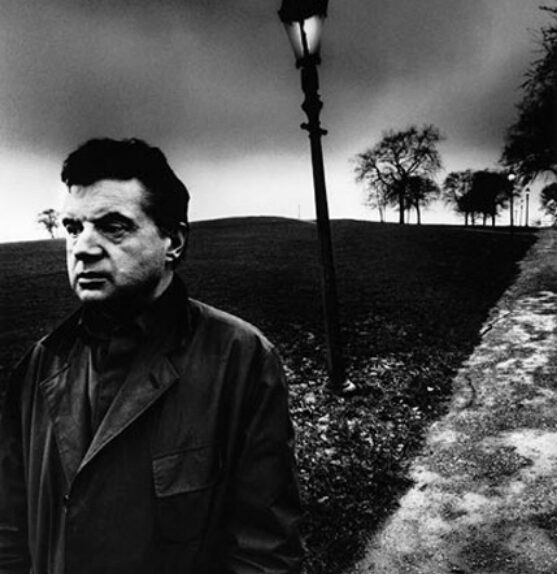

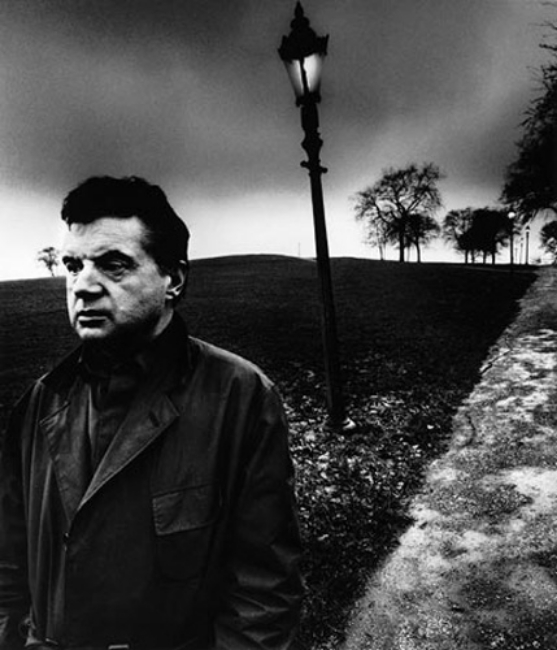

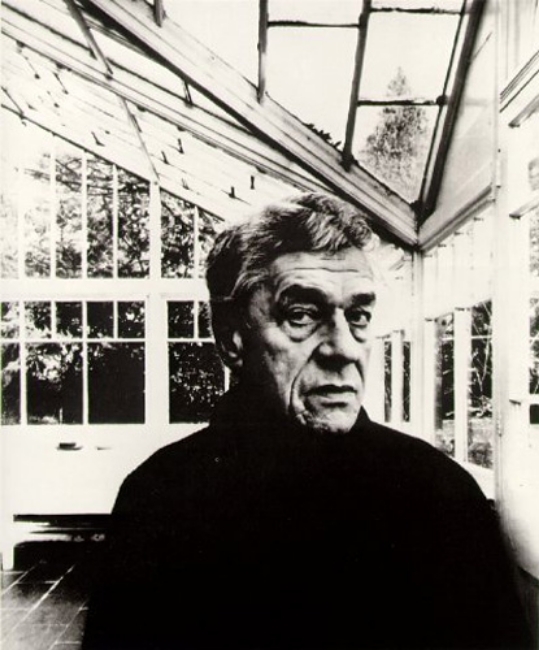

He turned to landscapes and to nudes, he began to explore the limits of formal portraiture. His approach to portraiture was a fairly radical departure from what was then in style. He accepted commissions to photograph famous men and women, but he had no interest in celebrating them. His portraits weren’t meant to flatter, or to reveal the subject’s ‘true nature,’ or even to document the person’s physical appearance. His portraits seem to suggest that famous people are as essentially unknowable as ordinary people.

He didn’t like for his subjects to smile. “When you take [a photograph of] someone smiling, they look stupid,” he said. He preferred his subjects to be looking off into the distance, largely devoid of expression, disinterested in the world around them. He encouraged that lack of connection with the world at large by refusing to connect with the subject; he avoided speaking to them, or even looking at them (other than through the viewfinder of his Hasselblad).

In his notion of portraiture the background is often as important as the subject (which makes sense, given his immense interest in landscape photography). He planned his locations with more care than he gave to his subjects. For example, Brandt had settled on a site for a portrait of Alfred Hitchcock (“It was to have been at Charing Cross Underground Station; there is an amazingly long empty corridor that looks as if it goes right under the river.”) even though he was never commissioned to shoot Hitchcock’s portrait. He commonly used a wide angle lens for his formal portraiture, and shot from waist level. The result was an image of oddly angled horizons, and a distorted perspective that one critic describes as “an atmosphere of mental precariousness.”

He printed those images in a stark, high contrast aesthetic that was anything but flattering. One of his subjects said everybody Brandt photographed looked as if they’d been sentenced to death. And yet everybody considered it something of an honor to have a portrait by Bill Brandt.

A number of art critics have advanced theories about Brandt’s work. They suggest his almost pathological reluctance to admit to his German heritage, his experiences as a bullied child, his years spent being treated for tuberculosis, his ongoing struggle with asthma, his antipathy for his father who sent him to boarding school—all these emotional traumas, they say, present themselves in Brandt’s work.

I don’t know—maybe it’s true. It’s certainly interesting to think about, and it certainly can shape our understanding of the man and his work. But how much does it matter?

His biographer, Paul Delaney, described Brandt as “a man who loved secrets, and needed them.” Certainly, almost everybody he photographed seems to have a secret—though whether that secret is inherent in the subject or planted there by Brandt, it’s impossible to tell. And, again, how much does it matter?

What matters is that Bill Brandt—whatever his secrets, whatever his traumas, whatever his motivations—took extraordinary photographs. What matters is that he didn’t limit himself to any genre of photography, but tried his hand at everything he found interesting.

“Everything is allowed and everything should be tried.”

I’m willing to let Brandt keep his secrets; I’m just glad he tried everything and let us see the results.