There was a generation of Hungarian photographers – all born around the beginning of the 20th century – who left Hungary at a young age and scattered their talent all over western Europe. Among them were André Kertész, Gyula Halász (better known as Brassaï), László Moholy-Nagy, André Friedmann (better known as Robert Capa), Martin Munkácsi, and a young woman named Eva Besnyö.

She was born in Budapest in 1910, a clever child who learned quickly. Some of her lessons were unpleasant. She learned about prejudice and she learned to be adaptable. Her father, Bela Blumengrund, was a lawyer who, in order to succeed in his practice, exchanged his Jewish birth name for one more Hungarian-sounding: Bernat Besnyö.

Her father expected Eva and her two sisters would all attend the university. Eva had other ideas. At the age of 18 she owned a small Kodak Brownie camera and knew she wanted to be a photographer. Encouraged and supported by her uncle, Besnyö convinced her father to allow her to forgo the university and instead become an apprentice to a photographer. Her father insisted she work with the best – József Pécsi, who owned a well-regarded studio specializing in portraits, advertising, and architectural photography.

For two years Besnyö worked as an apprentice in Pécsi’s studio, learning and mastering the fundamentals of practical photography and darkroom technique. She acquired a good camera (a Rolleiflex) and, more importantly, a copy of a photography book that would change the way she saw the world and, in fact, would change her entire life.

Published in 1928, Die Welt ist Schon (The World is Beautiful), by photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch, is a collection of a hundred photographs of repeating natural forms, industrial still lifes, and mass-produced objects. The photographs are precise, sharp, made with scientific clarity. The fashion in photography at that time was self-consciously poetic and romantic. With the release of Die Welt ist Schon, the New Objectivity movement in photography began. Eva Besnyö was determined to be a part of it.

In 1930, Besnyö was 20 years old; she’d completed her apprenticeship and wanted to leave Budapest. Her father felt that if she must leave home to practice photography, she should go to Paris, but Besnyö felt Paris was too locked into romanticism. Berlin offered new ways of thinking, new ways of expression. She saw how Renger-Patzsch was using the New Objectivity approach to photograph things, and how August Sander was using it to photograph people. Besnyö wanted to use the approach to explore the untidy interstitial territory between people and things.

In Berlin she found work with Peter Weller, who operated a photo-reportage agency. It was the perfect job for Besnyö; she was allowed – even encouraged – to wander around Berlin photographing everyday life. Her most well-known photograph (Boy with Cello) was made during this period.

As was the common practice of the time, most of her photographs in Besnyö’s Berlin period were published either under Weller’s name or under the name of his agency. But her work was being seen, she was getting paid, and other photographers knew the work was hers. Besnyö was happy.

She was also becoming politically active. Along with other photographers (including Capa and Moholy-Nagy) and local intellectuals, Besnyö attended workshops and lectures given by the Marxist Workers Evening School. She began to accept commissions through the NeoFot Picture Agency, which needed images of ordinary workers on the job – tradesmen making repairs, dock laborers, construction workers.

As a Jew and a budding Marxist, Besnyö was very much aware of the growing Nazi movement in Germany. In 1932, after two very productive years in Berlin, she decided to move to the Netherlands. In Amsterdam she joined with other artists, photographers, filmmakers, writers, and intellectuals who were fleeing Nazi repression.

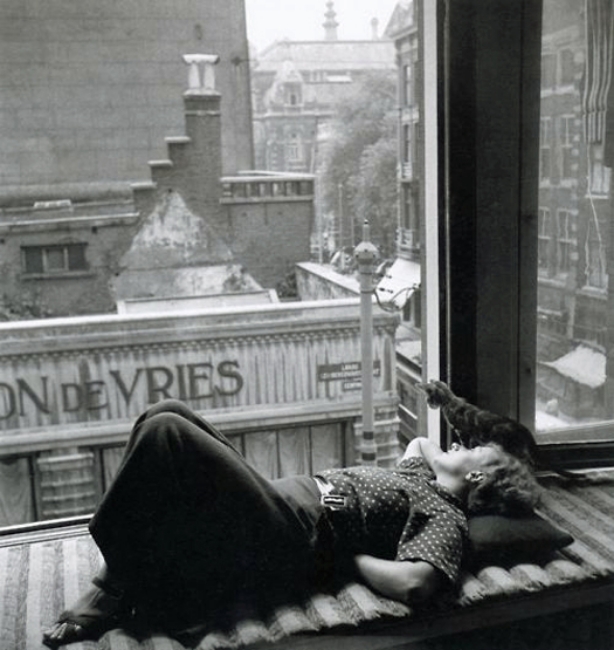

In 1933, Besnyö was given an individual exhibition by the internationally respected Van Lier art gallery. Even as her reputation as an artist grew, she remained an extremely competent working photographer, shooting portraits, architecture, fashion, and photojournalism as needed. Because her work was so diverse, it’s difficult to perceive the development of a personal, individual style. But she generally stayed within the basic parameters of New Objectivity, shooting from sometimes from unusual angles, seeking out diagonal lines when possible, always with an eye toward fusing dispassionate clarity with compassionate humanity.

Besnyö became increasingly political. In 1934, she joined an association of artists seeking to protect artistic and cultural rights against the growing Nazi influence. She also participated in an exhibition called Olympics Under Dictatorship, protesting the 1936 Olympic games which were held in Berlin.

Besnyö’s new homeland, the Netherlands, declared itself to be neutral at the beginning of World War II. Germany, however, refused to acknowledge that neutrality. On May 10, 1940 they invaded the Netherlands. Although there was some initial resistance by the Dutch Army, the Dutch government capitulated after the Nazis threatened to bomb the port city of Rotterdam. The German Air Force bombed the old town of Rotterdam anyway. More than 800 civilians were killed; around 24,000 houses were burnt and some eighty thousand people were left homeless.

Two months later, Besnyö photographed the ruins.

With the Nazis occupying the Netherlands, living and working conditions for Jews were severely limited. Besnyö was soon forbidden from any journalistic work. She was limited to accepting only private photographic commissions. Soon even that work disappeared. By 1941 the first group of Jews were deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. A year later Jews were required to publicly identify themselves by wearing a Star of David and the Nazis began building concentration camps in the Netherlands.

Eva Besnyö went underground. She obtained false identity papers and managed to eke out a small, limited life until the end of the war. Although most of her family survived the war, her father was less lucky; he died in Auschwitz. Of the 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands before the Nazi invasion, only 30,000 survived.

Besnyö remained in the Netherlands the rest of her life. She married, had a son shortly after the end of the war and a daughter three years later. She continued to be a working photographer and politically active. In 1970, when she was 60 years old, Besnyö began documenting the Dolle-Mina feminist movement, and continued to be a part of that movement for the next six years. In 1980, when she was 70, Besnyö was offered a Ritterorden (a knighthood) by Queen Beatrix; Besnyö rejected it. In 1999 she was given the Erich Salomon Prize – a lifetime achievement award given annually by the German Society of Photography. She accepted it.

Eva Besnyö died in 2002.

She summed up her approach to photography in a 1991 interview:

“In the beginning, the form was more important than the content. Slowly but surely that tendency switched, up until the arrival of feminism. Suddenly, the subject took over. Form is essential to me. Composition is important, and I would have disavowed myself had I not taken that into consideration, which was the case for a time. I hope to have found a balance between form and content.”

I rather think she did. Even though Besnyö never developed a distinctive personal style, she consistently remained true to a personal vision. Earlier I mentioned she’d gone to Berlin seeking a balance between the industrial approach of Renger-Patzsch and the human approach of August Sander. I believe she found that balance and whenever her work allowed, she maintained it. If you review much of her work you’ll note she rarely shows the faces of her human subjects. She doesn’t treat them as archetypes like Sander, nor as objects like Renger-Patzsch. Instead Besnyö treats them as universal stand-ins for everybody. People occupy the world, but as individuals they’re ephemeral. The people in her photographs aren’t important as specific people; they’re important in that they they represent humanity. Each man is Every-man, each woman is Every-woman, each child is Every-child.

In her refusal to cast herself as an artist, in her determination to be a working photographer, Eva Besnyö could be said to be Every-photographer.