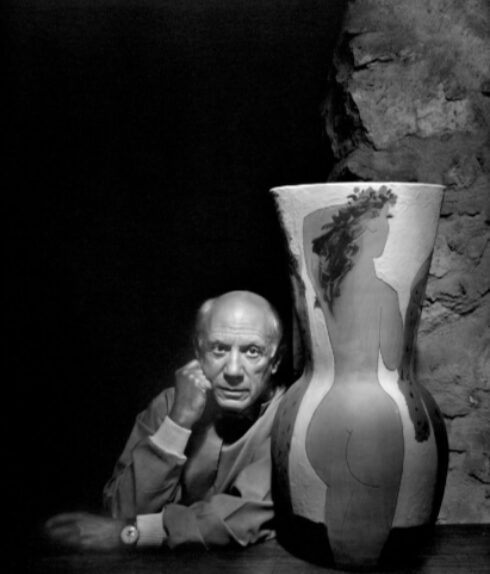

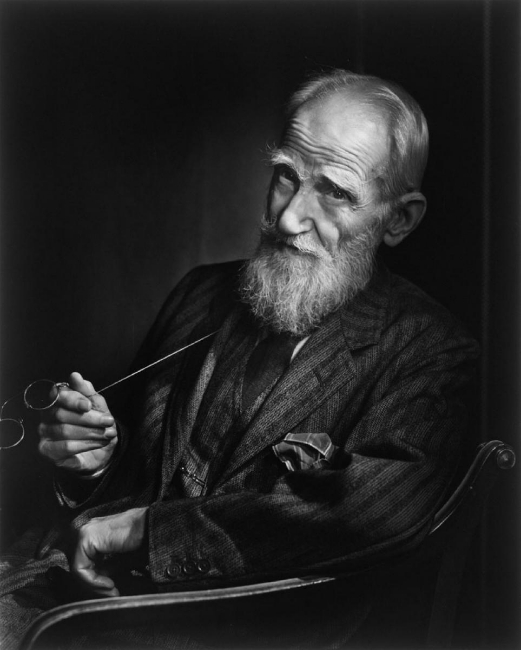

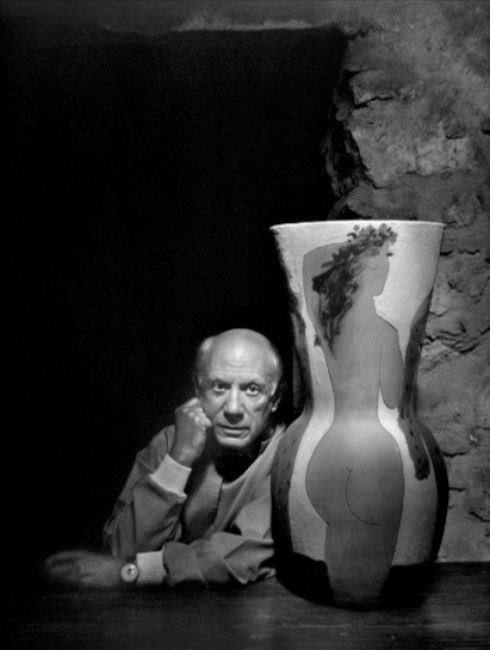

Yousuf Karsh is generally described as one of the greatest portrait photographers of the 20th century. The description is accurate. He created classically styled portraits of the rich and powerful and famous. His portraits were deliberately dramatic, rich in light and shadow, respectful of the subject, carefully crafted to emphasize the subject’s position in society. These were portraits of men and women who society felt deserved to be memorialized.

We don’t see much of that any more. It’s an outdated mode of photography and an archaic style of portraiture. There are social and cultural reasons for that, of course. But it’s impossible to look at a Karsh portrait and not appreciate the craftsmanship.

Karsh was born in 1908 in Armenia, which at the time was part of the Ottoman Empire. He came of age during the Armenian genocide, a period during which the Ottomans engineered the deaths of up to a million and a half Armenian men, women, and children. When he was 14 years old, his parents sent him to live with an uncle, George Nakash, in Canada. Nakash had a small portrait photography studio in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

Karsh apprenticed with his uncle, who nurtured the boy’s talent. When he was 20 years old, Karsh moved to Boston to work for another Armenian immigrant, John H. Garo, who’d made a name for himself shooting portraits of Boston celebrities. He stayed in Boston until 1932, when he returned to Canada and opened his own portrait studio in Ottawa.

During that period, while attending the Ottawa Little Theatre, Karsh encountered the technology that was to make him a great portrait photographer: incandescent theatrical lighting. Most photographic portraiture at that time relied heavily on natural available light. The new lighting technology allowed Karsh to create spectacular and stirring portraits. Those portraits drew in some powerful clients, including Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King. Using P.M. King as a reference, Karsh soon began to photograph many visiting dignitaries.

In 1941 Winston Churchill came to Ottawa. Karsh was given the opportunity to photograph the great man–but it was a small opportunity; he was granted only two minutes, a brief pause between the time Churchill was in the House of Commons chamber and when he was scheduled for a nearby meeting. Nobody had warned Churchill about the new lighting technology.

“The Prime Minister, arm-in-arm with Churchill and followed by his entourage, started to lead him into the room. I switched on my floodlights; a surprised Churchill growled, ‘What’s this, what’s this?’”

Churchill’s entourage laughed nervously at his response, which made Churchill more grumpy. To make matters worse, Churchill refused to put his cigar in the ashtray that was offered to him. With time running out, Karsh stepped forward and removed the cigar from Churchill’s hand. “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.” The resulting photograph became perhaps the most famous portrait of Winston Churchill.

Karsh’s career was made. He went on to photograph all the most famous and most important people of his era. Politicians, artists, composers, scientists, philosophers, writers…they all sat for Karsh. An article on Karsh in London’s Sunday Times stated “when the famous start thinking of immortality, they call for Karsh of Ottawa.”

Karsh once said “My chief joy is to photograph the great in heart, in mind, and in spirit, whether they be famous or humble.” Although he did accept a commission from the Ford Motor Company to photograph assembly line workers in an Ottowa factory, the humble rarely found their way in front of Karsh’s camera. For the most part, he photographed the famous and powerful.

He preferred large format cameras, but apparently was not locked into any single format. He used 8×10, 6×7,6×6, and 4×5 cameras. The camera was, it appeared, merely the recording device. It was the lighting that made Karsh Karsh. He frequently traveled with around 350 pounds of lighting equipment. One of his favorite techniques was to light the subject’s hands separately from the face.

It was once said of Karsh that he “transforms the human face into legend.” His use of heroic lighting and formal posing, to the modern eye, appears more about depicting the public persona of the subject rather than revealing anything about the subject as a person. The portraits are flattering in that they portray power. Karsh said, “If there is a single quality that is shared by all great men, it is vanity. But I mean by ‘vanity’ only that they appreciate their own worth. Without this kind of vanity they would not be great.“

Despite his tendency to exalt and glorify his subjects through dramatic lighting, Karsh continued to demonstrate an ability to use softer lighting and available light when it was appropriate to the subject.

One must consider Karsh’s background when judging his portraiture. He arrived in North America destitute, fleeing cultural persecution; the entire world would soon be entering a second global war. It was a period in which the fate of the world seemed to rest in the hands of great people…great leaders, great scientists, great politicians. It’s not so surprising that somebody who had lived Karsh’s life would be given to hero worship.

In one of several books he published, Karsh wrote: “the heart and the mind are the true lens of the camera.” I think it can truly be said that his portraits reflect the heart and mind of Yousuf Karsh.