At some point around 1910 portrait photographer August Sander began to undertake an incredibly bold project—a project of almost unimaginable scale. He’d decided to create a portrait series that would document the entire scope of contemporary German society. The portraits weren’t to be portraits of individuals, but rather portraits of societal archetypes. He wasn’t interested in shooting portraits of a specific banker or a specific bricklayer or a specific pastry cook; Sander wanted his subjects to represent all bankers, all bricklayers, all pastry cooks.

You have to wonder at the audacity of Sander, who was about 33 years old at the time. To embark on a project of such staggering proportions—to document an entire culture—seems amazingly arrogant. To Sander, however, it was more an exercise in persistence. All it would take was film and time, and he was prepared to give it.

The project would be interrupted by two world wars, by personal tragedies, and by political repression. Yet Sander was dedicated and persistent. If, in the end, the staggering number of photographs he amassed failed to achieve the goal he was after, it remains one of the most important and influential collections of images ever created.

Sander was born in 1876 in the town of Herdorf. His father was a carpenter working for a mining operation. As a young man Sander attached himself to a photographer hired by the mining company and developed a fascination with photography. With the help of his uncle, Sander bought a camera and darkroom equipment. That experience allowed him to spend his compulsory military service (1897-99) as a photographer’s assistant.

After being mustered out of the military Sander took a position with a portrait studio in Linz, Austria. Within a year he’d become a partner in the studio, and by 1904 he was the sole proprietor. In 1909 he moved his studio to Cologne, Germany. Buoyed by success and perhaps bored with shooting what he later called “sweet-looking, posed studio portraits” Sander began exploring the countryside on bicycle and photographing the farmers he met. Shortly thereafter he began his lifelong campaign to document the German people.

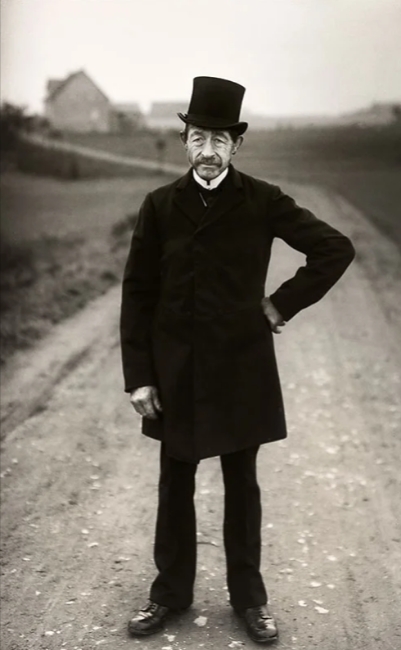

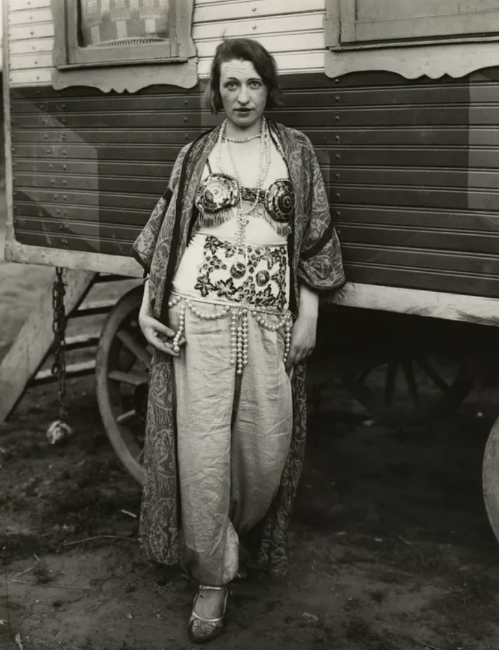

Sander, like many of that era, believed in the faux-science of physiognomy—the belief that a person’s physical appearance reflects character or personality. “More than anything else,” Sander wrote, “physiognomy means an understanding of human nature.” By photographing people he encountered and classifying them according to seven broad archetypal categories (The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City, and The Last People—this latter last category included homeless persons, beggars, the disabled, etc.), Sander believed he would create a scientific, visual account of the nation’s social order.

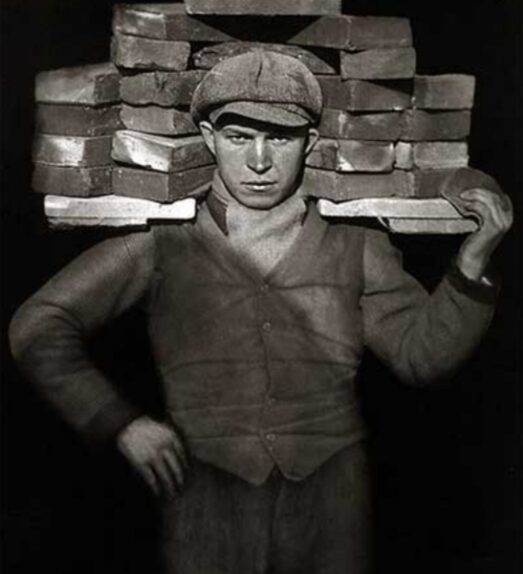

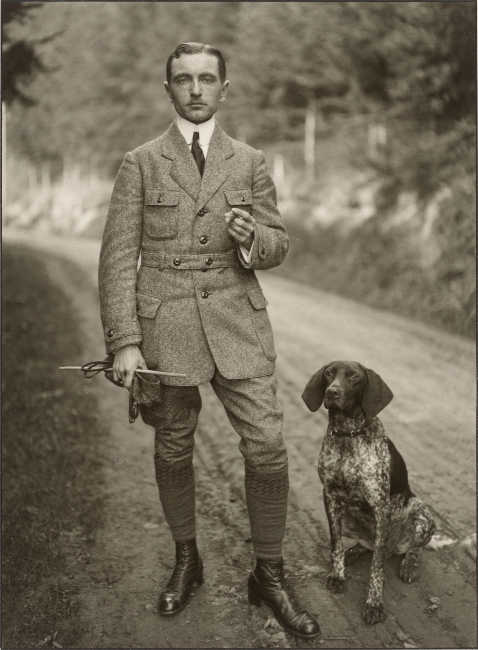

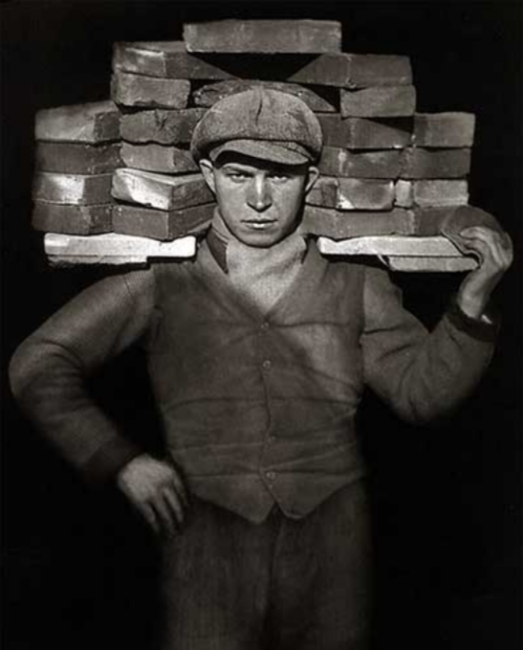

Sander’s approach to the work was intended to be purely documentary. “The essence of all photography,” he said in a 1931 radio interview, “is the documentary manner.” He therefore photographed his subjects simply and without emotion. His subjects are generally in the center of the frame, usually directly facing the camera, most often presented in full body (or nearly so). There is little or no close-up work at all; the lighting is natural and clear; there is nothing unrelated in the frame to distract the viewer from the subject. Even the titles of the photographs are devoid of individuality; the subjects are identified only by their place in the social order. In essence, Sander approached these photographs less as portraits than as object studies.

In truth, the contemporaneous viewer would have been able to decipher much about the subject by his dress and demeanor—education, social status, the level of social influence, income. Take, for example, the photograph of the farmer from the Westerwald. Simply by looking at this photograph we cannot determine that the subject is a farmer, but by identifying him as such Sander encourages the viewer (and, again, especially the contemporaneous viewer) to deduce a great deal about him. He’s a farmer who is able to afford such a fine coat—a coat which, however, doesn’t match his trousers—a farmer whose hands are clean and whose posture is unbent. The astute observer could determine where this farmer fell in the broad spectrum of farmers.

In pre-war Europe at the beginning of the 20th century class distinctions and divisions were still very rigid. While communists and anarchists openly deplored such social arrangements, much of the German population found the predictability of social class to be comforting. People understood where they fit into society. That sort of inflexible social situation had begun to crumble even before World War One. Afterwards, the collapse escalated.

The First World War began when Sander was four years into his project. Although he’d already completed his compulsory military service, Sander was conscripted and remained in the Army until the end of the war in 1918. At that point, he resumed both his portrait studio and his personal project.

What is most remarkable about Sander’s post-war portraits is that his approach remained exactly the same as it was before the war. It must be remembered that while Sander photographed his pastry cooks and bricklayers, Germany was in the process of falling apart. In the thirteen years following the war, there were seventeen different governments. Inflation was staggering, and made only worse by rampant counterfeiting. Unemployment reached 40% at one point. There were food riots. Suicide rates tripled. The defeat of Germany in the war and the punitive sanctions imposed on it resulted in chaos—socially, economically, politically. Some families who’d been wealthy or middle class became poor, and some working class folks—especially artisans and skilled tradesmen, became well-to-do. Many people were made homeless, either by the destruction associated with war or through the economic collapse. Beggars, many of whom were war veterans, prowled the streets and laborers had to travel to find work. Women, especially war widows, were forced to find work, often in non-traditional roles.

But you see none of that overt chaos in Sander’s work. He continued to photograph itinerant laborers as if they’d always been laborers, bricklayers as if they’d always been and would forever continue to be bricklayers. As though the German people he’d set out to document in 1910 hadn’t changed, as though the German society hadn’t changed. And in a way, that innocent, oblivious, universalist approach makes the portraits all the more compelling.

In 1929 Sander published Antlitz der Zeit (generally translated as The Face of our Time, a book of 60 portraits from his project. Despite the fact that the book was published at the beginning of the global Great Depression, it was modestly successful. Sander made plans to complete his project and publish a seven-volume series of books based on it.

The political climate Sander was ignoring in his portraiture, however, soon made his plan impossible. Although not yet in complete control of the government, the rise of the Nazi party was making itself felt throughout German society. The anarchist Erich Mühsam (the man sitting in the center of the three revolutionaries in Sander’s photograph above) was arrested by Nazi officers, who shattered his teeth with repeated strikes of a rifle butt and branded a swastika on his scalp; eventually he was beaten to death and his body hung up in a latrine. It is highly improbable that Sander was ignorant of such events.

The Nazis were elected to a majority in 1933. The following year Sanders son, a communist, was arrested for belonging to the Socialist Workers’ Party and sentenced to ten years in prison (he would die there, just a few months short of his release date, from a ruptured appendix which the prison staff refused to treat). In 1936 the Nazis confiscated all the publisher’s copies of Antlitz der Zeit; the printing plates were destroyed and the book was officially banned because the subjects did not adhere to the ideal Aryan type.

After his book was banned, Sander began to turn his camera more toward landscape and architectural photography. He accepted advertising commissions and completed botanical studies. He also continued to quietly photograph the German people, including soldiers and officers in the German Army.

When the Second World War began Sander and his wife moved away from Cologne, which was a high value target for Allied bombers. Over 250 bombing raids leveled the city center, causing more than 20,000 civilian casualties. Sander’s studio in Cologne was destroyed, though their apartment—where between 25-30,000 of his negatives were stored—was spared. Ironically, the year after the war ended Sander’s apartment caught fire and those negatives were lost.

After the war Sander continued to work on his project, though his belief in the ‘science’ of physiognomy must have been shaken, if not completely destroyed. His best work would remain the photographs he took between the wars. His attempt to create a scientific document of a nation was, it must be admitted, a failure. But because of the way he approached them, the portraits he created carry an unintended power.

Modern portraiture revolves around the notion that a portrait should reveal something about the subject; this approach existed even during Sander’s lifetime. But he wasn’t photographing individuals; he was photographing archetypes. He made no attempt to penetrate the masks of those he photographed; he allowed them to present themselves as they wished to be seen. As a result, his subjects offered themselves up with sincerity, without any hint of irony, without fear of being made to seem ridiculous, without any melodrama.

August Sander may have been inspired by the pseudo-science of physiognomy. He may have attempted to photograph archetypes. But in the end, the thing that stands out most clearly in Sander’s work is the undeniable humanity of his subjects.