I recall the first time I saw a photograph by Anders Petersen. It was an image of a bare-chested young man who appears to be blissfully drunk or stoned in the embrace of an older woman who is laughing uproariously. I had no idea the photo had been taken by “one of the most important European photographers living today.” I didn’t see the photo in an art book or a photography magazine; I saw it on the cover of Tom Waits’ classic album, Rain Dogs.

Petersen took the photograph in the late 1960s. Twenty years later, Waits released the album. It was another twenty years before I discovered the photograph on the album jacket had been shot by Petersen.

If any photographer personified the music of Tom Waits, it’s Anders Petersen. And if any musician could embody the photographic style of Peterson, it’s Waits. They’re each, in their own way, troubadours of the dispossessed. They’re each drawn to the edges of society where marginalized people gather together. They each have a penchant for a sort of poetry of the hopeless.

Anders Petersen was born in 1944 in the small town of Solna, Sweden. His parents separated when he was young and he lived with his grandmother, a very respectable woman. But respectability ranks rather low on the hierarchy of the needs and interests of young men.

“After I graduated, I fled to Hamburg to try to get rid of this rucksack of bourgeois thinking and behaving, the lies and so on.”

Petersen arrived in Hamburg in 1962 and quickly found his way to the Reeperbahn, the city’s red light district. Even then the Reeperbahn had a history of drawing people looking for a good time. It’s located near the port, and at the time was home to more than two dozen brothels. Sailors, of course, came for the prostitutes, but others came for the bars and the music. The Reeperbahn is the Hamburg neighborhood where the Beatles honed their craft, playing in rowdy bars and nightclubs. They were on their third visit to Hamburg when Petersen’s first visit began.

John Lennon said “I might have been born in Liverpool, but I grew up in Hamburg.” The same could be said of Anders Petersen. Eighteen years old and relatively innocent, he arrived in Hamburg, met a Finnish prostitute named Vanya, and promptly fell in love with her. He apparently followed her, puppylike, around the Reeperbahn. She introduced him the bar that would eventually make him famous – the Café Lehmitz. It will probably come as no surprise that Vanya eventually tired of her callow admirer and broke off their relationship. She told Petersen to leave Hamburg.

So he did. Petersen returned to Sweden and went back to school. He wanted to do something in the arts.

“I tried painting, but it was too lonely and I am a social person. I tried writing, but it was even more lonely. I saw how these fashion photographers lived, with the beautiful girls and the big parties, and I decided to follow that road.”

He enrolled in a photography program with the intent of becoming a fashion photographer. Early in his studies, Petersen came across a photograph taken by .well-known Swedish photographer Christer Strömholm. The photo showed a Parisian graveyard in winter, footsteps tracking in the snow–and it changed everything for the young man.

He abandoned his plan to become a fashion photographer and arranged to study under Strömholm. A few years earlier Strömholm had shot a series of photos of transvestites at Place Blanche in Paris. Petersen, who had encountered transvestites and transgendered people in the Reeperbahn was quite taken with the style and attitude of the photos. When he finished his studies, he packed up and moved back to Hamburg–back to the Reeperbahn, back to the Café Lehmitz.

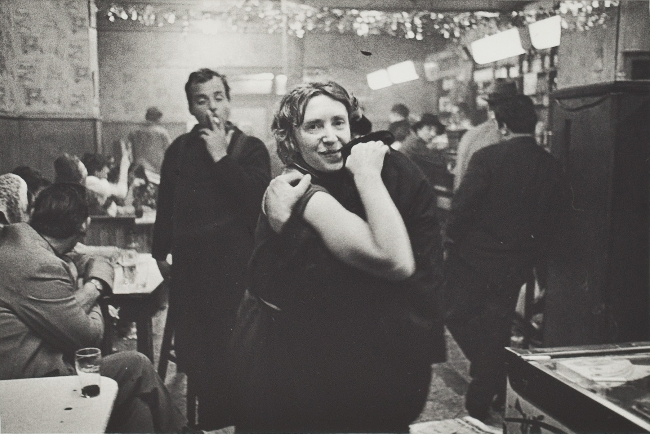

The Lehmitz became Petersen’s second home and its people became his extended family. The bar’s clientele was diverse, to say the least. Prostitutes, of course. And where there are prostitutes, there are sailors. But the bar was also frequented by cab-drivers and dockworkers, by dancers and petty criminals, by aging transvestites, by men and women who were too old and dissipated to be welcomed in other establishments. For the next three years Petersen lived with and photographed these people.

Appropriately, the Café Lehmitz was the venue for his first show. Petersen printed 350 of the portraits he’d show in the bar and pinned them, unframed, to the nicotine-stained walls.

“If people recognized themselves, they could take the image home. It only lasted four or five days, until there were no pictures left…just a small one of me. It was still there ten years later.”

Eventually those images were published in a book of the same name, Café Lehmitz. It was a seminal work in European photography, as influential in Western Europe as Robert Frank’s The Americans was in the U.S. It perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the Reeperbahn at the end of the 1960s.

Petersen has continued to work in the same immersive way. He is still drawn to a community of marginalized people–convicts, the inhabitants of a home for old people, a psychiatric hospital. He gets to know the people, he involves himself in their lives and lets them into his. “To me, it’s the encounters that matter,” Petersen says. “Pictures are much less important.”

Pictures may be less important than relationships, but photography is seductive. “That 15th of a second; once you’ve been there, you keep on wanting to get back.” Petersen has said that every photographer is a voyeur, “but you have to fight against it.” After four decades of shooting very personal, very intimate images, he finds it harder to maintain a balance between interacting with the world as a photographer and being a person.

“When you have been taking many pictures through the years you have to be very careful, you have to be not too much of a photographer, you have to be a human being before everything.”

And yet he is never without a camera. He keeps a small Contax T3 with him at all times and he shoots a lot of film. His office is jammed with thousands of black and white contact sheets. “So many photographs. Mostly, I never know what to do with them, so I just put them away. It’s a life, you see, not really a profession.”

The Café Lehmitz is gone now. In it’s place is a non-denominational church. The habitués of the bar are either dead or scattered away. “They lived a brutal and tender life that I had never experienced before,” Petersen has said, “but that changed my way of looking at the world.”

There is, perhaps, something sad in that. Something tragic. But the fundamental mechanism of tragedy is inevitability. Nobody ever expected the Café Lehmitz to last forever. None of its patrons ever expected to become successful; they were always seen by society (and often by themselves) as disposable. The only unanticipated variable in all this was Anders Petersen and his camera.

Because of him, the Café Lehmitz and its people will be remembered. It’s probably a better fate than any of them contemplated for themselves.