Some lives are so out of the ordinary that they seem to verge on fiction. Adolfo Farsari lived such a life. He was born in the town of Vicenza in 1841, which was then part of the Austrian Empire. In 1859, when he was 22 years old, Vicenza was annexed into the kingdom that would eventually become the modern nation of Italy. Farsari, apparently pleased by the annexation, joined the Italian army. Two years later Italy became an independent kingdom.

It’s unclear why he left the Italian army, but in 1863 Farsari left Italy and emigrated to the United States. An ardent abolitionist, he joined the New York State Volunteer Cavalry and took up arms in the American Civil War. After the war he married a U.S. citizen, became a U.S. citizen himself, had a pair of children, and remained in the U.S. for the next decade.

To that point, Farsari’s life was a fairly common American immigrant story. What happened in 1873, however, was anything but common. His marriage failed, he abandoned his wife and children, and took ship for Japan.

It must be remembered that for centuries Japan had restricted its international trade to only two nations: the Dutch and the Chinese. Two decades before Farsari set sail, Japan had been forced to open its borders to foreign trade (literally forced; the primary negotiation tactic relied on half a dozen gunships anchored in the harbor). To the Western mind, Japan was perhaps the most mysterious and exotic land on the planet.

Farsari arrived in Yokohama, the primary base for foreigners in Japan. He set up a shop with a partner, trading in goods primarily of interest to other Westerners: tobacco products, newspapers and magazines, maps, stationery, guidebooks. More importantly (for us, anyway), they also sold books of photographs of Japan.

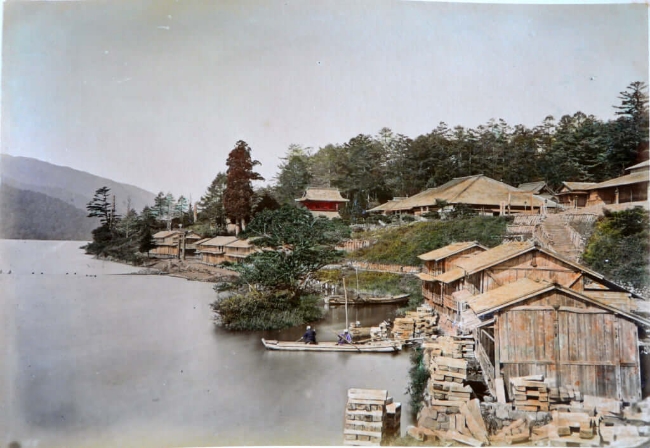

Although the partnership ended, Farsari persevered. He expanded his business into publishing and commercial photography. By 1883 his income was almost entirely photography-related. He taught himself photography and began to shoot photographs specifically intended for local Japanese guidebooks and travel albums, hand-coloring many of the sepia prints to give them a more “life-like” feel. He eventually employed a small stable of Japanese colorists, each of whom could produce up to two hand-colored prints per day. He also hired and trained a number of Japanese photographers.

In 1886, Farsari suffered a serious setback–one that could have caused him to give up the business, leave Japan, and start over again somewhere else. A fire at his studio destroyed all his stock, including his negatives. Instead of abandoning Japan, he set off on a five-month tour of the country, photographing the people and places he encountered. A year after the fire, Farsari had amassed more than a thousand negatives.

Farsari didn’t consider himself an artist. Perhaps if he had been an artist, if he’d been schooled from an early age in a vigorous European artistic tradition, his aesthetic would have been firmly established before he arrived in Japan and his photographs would have reflected that. But he wasn’t an artist and he wasn’t trying to make art; he was simply an entrepreneur creating a product for a market. Because that product was primarily intended for Western eyes, his photographs concentrated on subjects of particular interest to Westerners: landscapes and images depicting the lives of Japanese people. But because he learned photography in Japan and his subject matter was Japanese, his compositions were influenced by Japanese artistic sensibilities. As a result, his work became prized in both the Western world and in Japan.

In addition to the photographs he took for his publications, Farsari also began to engage in portraiture. Although many of his portrait clients were Europeans living in or visiting Japan, he also photographed many well-to-do Japanese. His growing fame was such that he could charge half a ryō for a portrait, which at the time was the equivalent of a month’s income for a local skilled artisan. Being an entrepreneur at heart, he sometimes ‘double dipped’ by including some Japanese portraits in his travel albums.

The Japanese had–and still have–a tradition of meisho, images of locales famously associated with works of poetry or literature. These locales were commonly depicted in ukiyo-e, reproducible woodblock prints. Perhaps the most famous of these meisho is Utagawa Hiroshige’s Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, prints showing the lovely rest areas on the road linking Edo and Kyoto. Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e series had been completed only forty years before Farsari arrived in Japan.

Farsari didn’t recreate Hiroshige’s work, but he created something similar–photographic travel albums showing both the famous and the obscure locations of Japan, as well as photos depicting the manners and customs of the people who lived and traveled there. These albums became staggeringly popular among both visitors to Japan and Westerners who had an interest in the nation. Rudyard Kipling gave the work an enthusiastic review, referring to Farsari as “a nice and eccentric chap” whose photographs were “known from Saigon to America.” A copy of one of his photo albums was even presented to the king of Italy. Farsari’s studio was so successful that he was granted the honor–and it was an astonishing honor for a European–of being granted the exclusive rights to photograph the Imperial Gardens in Tokyo.

Because of his popularity and access to restricted or private locations, Farsari was able to photograph areas barred to citizens of Japan. Even though he made his photographs to appeal to Westerners, his photo albums became increasingly popular among wealthier Japanese.

In the mid-19th century, most Japanese were peasants tied to the lands they worked. Very few people traveled any distance from their farms and local villages. One of the strange artefacts that grew out of the popularity of ukiyo-e and travel albums like those produced by Farsari is that those images not only shaped the perceptions of outsiders, they also influenced how the Japanese perceived themselves and their nation.

Perhaps the best example of this is the modern popularity of the Daibutsu, the gigantic statue of the Amida Buddha in Kamakura. The 45 foot tall bronze statute held relatively little interest to the Japanese public until after it began to appear in Farsari’s travel albums. It quickly became a favorite destination for Japanese pilgrims as well as foreign visitors.

As he grew older and wealthier, Farsari began to plan to return to his hometown in Italy. He attempted to regain his Italian citizenship (which he’d first gained when Vicenza became part of the kingdom of Italy and lost two years later when he became a U.S. citizen), seemingly without success. Nevertheless, in 1890 he returned to Vicenza. Although retained ownership of his photographic business in Yokohama, he never returned to Japan. Farsari apparently bought his old family home and lived there until he died in 1898 at the age of 57.

At the time of his death, Adolfo Farsari had lived in Japan longer than he’d lived in his native land. He cannot be said to be truly Italian, since his hometown was part of the Austrian Empire when he was born. Yet he was clearly not Austrian, since his hometown became part of the kingdom of Italy. Nor was he American, despite the fact that he’d become an American citizen and fought in the American Civil War. Nor was he Japanese, despite all the years he’d lived there. He was, in effect, a man without a nation. In the end, the only label that truly applies to Adolfo Farsari is this: photographer.

As labels go, it’s not a bad one to have.