Kohei Yoshiyuki was an ordinary commercial photographer who spend nearly a decade documenting a strange subterranean aspect of Tokyo culture. After publishing his work, he became notorious for a short period of time. Then Yoshiyuki quietly disappeared from the art scene.

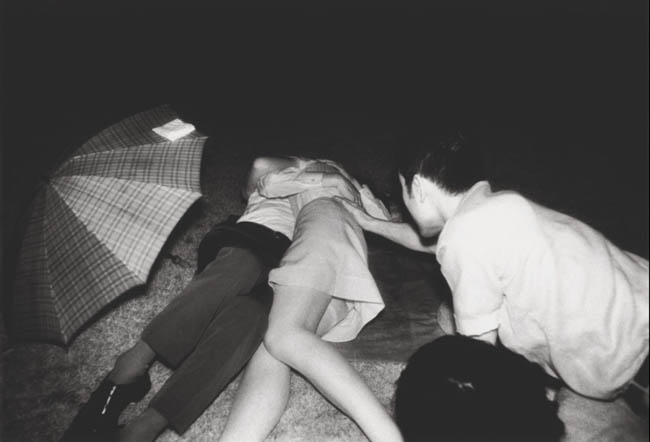

It all came about by accident. Yoshiyuki and a companion were walking through Chuo Park in the Shinjuku section of Tokyo one night when they encountered a man and woman having sex on the ground. Just as surprising, they saw two other men very near the couple, intently watching. Yoshiyuki was fascinated by what he’d witnessed–not just the couple engaged in intercourse, but also by the voyeurism–and decided to document it. He learned of two other parks in Tokyo where lovers and voyeurs gathered.

“My intention was to capture what happened in the parks, so I was not a real ‘voyeur’ like them. But I think, in a way, the act of taking photographs itself is voyeuristic somehow. So I may be a voyeur, because I am a photographer.”

Yoshiyuki doesn’t seem to have been terribly burdened by the ethical issues involved in the project; he was more troubled by the technical difficulties of shooting photographs in the darkness of the park. After some research he discovered Kodak made infrared flash bulbs. Those bulbs combined with 35mm infrared film enabled him to prowl the parks in the dark and record activities he could barely see with the naked eye.

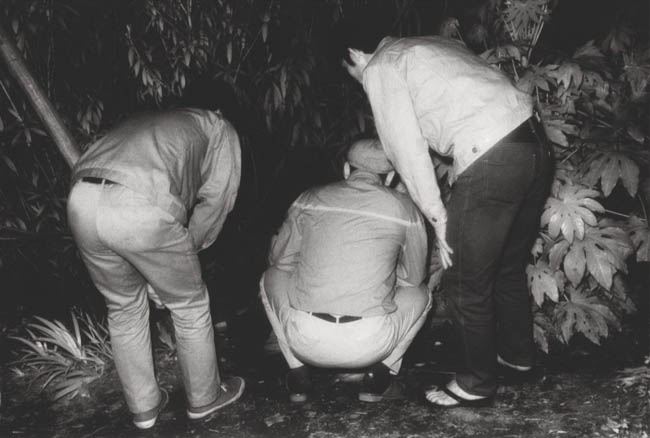

That was also a problem. Working in the dark, it was nearly impossible to see what was in the frame. Yoshiyuki often had to guess at the image composition. The exposed film revealed more than was actually visible in the viewfinder, more than was visible to the eye. He discovered the voyeurs he captured on film not only crept close enough to see the couples having sex, they sometimes even engaged in a sort of furtive groping of the couples’ arms and legs. The voyeurs were, in fact, occasional participants.

He photographed it all–couples by themselves, couples surrounded by onlookers, heterosexual and homosexual pairings, the voyeurs. From 1971 to 1979 Yoshiyuki haunted the parks of Tokyo taking what critic Vince Aletti called “among the strangest photographs ever made.” The photos have the gritty and grainy quality of surveillance imagery. It makes them seem more real while also injecting a sense of emotional distance between the photographer/viewer and the subjects. Despite the sexualized content of the photographs, they are distinctly non-erotic.

In 1979 Yoshiyuki’s park photographs were exhibited in a Tokyo gallery. The exhibit was as odd as the photos themselves. He had the images enlarged to nearly life size, accentuating both the realism and the graininess. The gallery itself was deliberately kept very dark; visitors were issued flashlights to find their way through the gallery and look at the photographs. The size of the photos and the darkness meant viewers were unable to see the entire image at once; they were forced to examine the image in sections. That approach radically changed the viewing experience. Yoshiyuki’s response to the exhibit was appropriately voyeuristic.

“I really enjoyed watching people looking at the photographs. Since the points of light were also their lines of sight, I saw things that were totally unexpected.”

The subject matter combined with the unique viewing approach made the exhibit a sensation. When the exhibit closed, Yoshiyuki destroyed the large prints. The following year, 1980, many of his park photographs were published as a book entitled Kōen (Park). Some of the photos were subsequently purchased by major international museums, such as MoMA in New York City and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. In critical reviews of the work, Yoshiyuki’s name was mentioned in conjunction with other famous Japanese photographers.

Despite his growing celebrity, Kohei Yoshiyuki essentially vanished from the art photography world. He sloughed off his pseudonym along with his fame and reportedly returned to his quiet life as a commercial photographer shooting family portraits for a major Tokyo department store. Although there was a short-lived retrospective of his work in 2006, there has been no new work from him.

Three decades after they were taken, the photographs–and the manner in which they were taken–remain controversial. Although they’re not actually sexually explicit, the images retain a sort of lurid sweatiness that many viewers find rather queasy-making. They still make people uncomfortable.

It’s not that uncommon for photographers–especially street photographers–to turn the viewer into a sort of secondhand voyeur. The peeking-over-the-shoulder perspective of Yoshiyuki’s work, however, powerfully reinforces that voyeuristic feeling, a feeling that’s further enhanced by the sad fact that there’s nothing casual about the ‘casual sex’ we see in the photographs. The sexual activity seems hurried, nervous, and anxious both on the part of the couple and the watchers.

The night itself also plays a part in creating the emotional texture of the images. In some of the photographs, the lights of the city are visible in the background, and we are at least subconsciously aware that the people in these photographs have deliberately chosen an outdoor public arena cloaked in darkness for their liaisons. The nocturnal environment underlines the almost predatory approach of the voyeurs, who generally run in packs and silently stalk the couples they watch.

Yoshiyuke, of course, wasn’t the first artist to document this sort of transgressive voyeurism. He wasn’t even the first Japanese artist to do so. There are, for example, extensive collections of ukiyo-e woodblock prints from the 18th and 19th centuries depicting voyeurism. What Yoshiyuki did was remove any filter of romanticism–or eroticism, for that matter–from the behavior.

Work of this sort inevitably raises questions. At what point does voyeurism become art? Does voyeurism necessarily have to be dissociated from an artistic pursuit? Does art justify the behavior of the photographer? By engaging in these behaviors in public–even under cover of night–do the lovers give up their expectations of privacy? Do the voyeurs give up their expectations of privacy? Do–or should–photographers have the right to infringe on that privacy in the name of art? By looking at these photographs are we, the viewers, complicit in any breach of ethics made by Yoshiyuki?

I think those are probably worthwhile questions to ask. But I confess, I was reluctant to include Kohei Yoshiyuki in the Sunday Salons. Not because of the sexual nature of the images, but simply because I don’t find the work interesting. But the questions are interesting.

If not for the coincidental encounter Yoshiyuki and his friend had in the park, we’d almost certainly never have heard of him. Aside from the questions raised by his photos, his absence from the photographic community wouldn’t be a loss. But he shot the photos, and we’ve looked at them, and we’ve asked the questions.

Now we’re stuck with him.