Sex, death, and exquisite shoes. That’s the legacy of fashion photographer Guy Bourdin. And the shoes–they’re a distant third, almost an afterthought.

He was born in Paris in 1928. His mother was Belgian, his father Spanish; both were very young. While he was still an infant, Bourdin’s parents abandoned him. He was sent to live with his paternal grandparents, who owned a restaurant in Paris. Some years later his father remarried and re-entered his son’s life. His mother, however, remained absent. Although she called him periodically at the restaurant (young Bourdin, who was reluctant to speak with her, would be locked into the restaurant’s telephone booth in order to force him to speak with her), he only met her once. The only memory Bourdin had of his mother was of an elegant Parisienne, heavily made up, with light red hair and very pale skin.

In 1948, not long after the end of World War II, Bourdin was conscripted and entered the French Air Force. There he was trained as an aerial photographer. What he really wanted to be, though, was a painter. Unfortunately, Bourdin’s talent was mediocre at best, and to his credit, he was astute enough to realize that.

At some point during his military service Bourdin saw one of Edward Weston’s famous photographs of a bell pepper, and began to understand photography had aesthetic potential beyond the mere act of documentation. In 1950, at the end of his two years of military duty, Bourdin returned to Paris, determined to be a photographer. He discovered that Man Ray lived nearby and went to see the famous surrealist photographer. He was turned away by the artist’s wife. Bourdin returned five more times, and each time she turned him away. On the sixth time, Man Ray himself answered the door and invited him in. He became Bourdin’s mentor.

After four years of trying to exist as an art photographer, Bourdin was hired by French Vogue to photograph hats. Fashion photography in 1954 was not particularly innovative; there was near-uniformity in the styles and poses used by the industry’s photographers. The images found in high fashion magazines were fairly formulaic. Even within those confines, however, Bourdin’s feel for art asserted itself. His models might have to use traditional poses, but he could put them in front of nontraditional backgrounds. No Eiffel Towers for Bourdin, no Arc de Triomphe. For his first fashion shoot for Vogue (in 1955), he put his model in front of a butchers shop displaying calf heads hung on hooks.

Bourdin began to develop something of a reputation and became a favorite of Francine Crescent, the editor of French Vogue. In the early 1960s, she introduced him to Roland Jourdan, the head of Charles Jourdan shoes. This began a relationship that changed the nature of fashion photography forever.

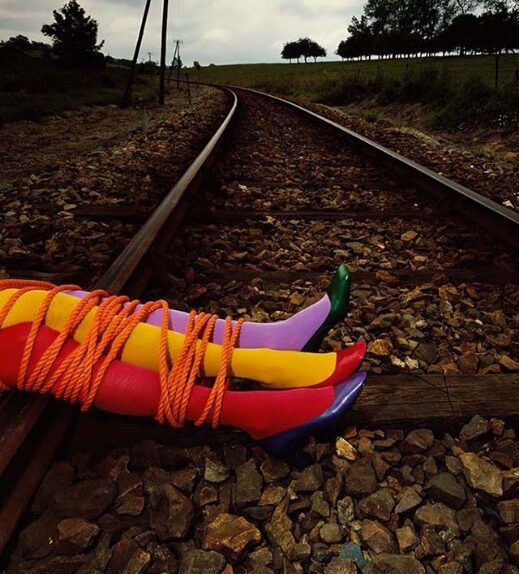

Bourdin is said to be the first fashion photographer to shift the emphasis from the product to the image. The product–in this case, Charles Jourdan shoes–became an incidental aspect of the image. The shoes might be in the photograph, but the photograph was not of the shoes. Bourdin began to construct and photograph strange narratives that existed independently of the product.

This style turned out to be good for the magazine, which drew more attention and therefore generated more advertising sales. It was good for the product, even if was incidental to the image, because it brought attention to the brand. And it was good for Bourdin, who was soon given unparalleled freedom to photograph whatever he wanted. By the 1970s, he was given complete artistic control over ten pages in each monthly issue of French Vogue.

As Bourdin’s artistic license increased his images became still more abstract, even less concerned with the product, much more idiosyncratic, and overtly sexualized. He introduced concepts of violence, suggestions of perversity, and expressions of death into his work. Most remarkably, he did it using incongruously bright colors. Bourdin’s approach has become ubiquitous, especially in European fashion magazines. Modern fashion photographers like Steven Meisel, David LaChappelle, and Nick Knight continue to work those same themes in that same style with those same bright colors.

Bourdin’s eccentricities extended to his models. There is a Stepford Wife quality to many of his models; they tend to look alike–pale skin, long light red hair. All very reminiscent of his memory of his mother. “He remembered her in a very romantic way,” according to Francine Crescent. Clearly, given the photographic treatment given these models, Bourdin’s feelings about his mother were powerfully conflicted.

That casually sadistic treatment of women wasn’t limited to the photograph. His behavior toward his models, his wife, his girlfriends was neglectful and dismissive at best, cruel and abusive at worst. He was often at his worst. Bourdin wasn’t simply unaware of their suffering, sometimes he appeared to enjoy it. On one occasion Bourdin wanted to cover the pale bodies of two models in tiny black pearls. He had his assistants cover the models with glue and attach the pearls. The layer of glue interfered with the skin’s ability to regulate temperature and exchange oxygen; both models passed out. As his assistants hurried to remove the pearls and the glue, Bourdin is reported to have said “Oh, it would be beautiful to photograph them dead in bed.”

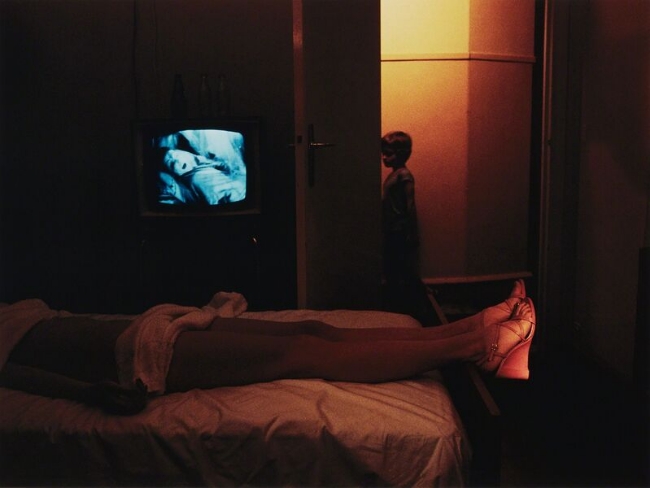

His personal life was equally disturbing. Bourdin dominated his wife and his various girlfriends, often removing their telephones, refusing to let them have visitors or leave their apartments, locking them in when he left. One of his girlfriends hung herself (her body was discovered by Bourdin’s 13 year old son). Another attempted suicide by slashing her wrists. A third died in a fall. His wife died, apparently of a drug overdose while in bed watching television.

Despite all this, Bourdin continued to be hired to shoot his strange conceptual fashion photographs. In fact, one image shot for Charles Jourdan shoes Bourdin shows a woman collapsed on a bed, the nearby television playing, the silhouette of a young boy standing in the doorway. He had conflated the events surrounding the death of his wife and his girlfriend into a single image.

Bourdin was as dismissive of his work as he was of the women in his life. He never bothered to file his negatives, transparencies or prints; they were left scattered around his studio–a windowless, black-painted space with neither an office nor a telephone. He refused to exhibit his photographs, refused all offers of publishing them in book form. In 1985 Bourdin was awarded the Grand Prix National de la Photographie by the French Ministry of Culture. He refused to accept it. This is all the more telling since many of his contemporary fashion photographers, like Helmut Newton, were constantly promoting their own work. It wasn’t until a decade after his death that Bourdin’s work was published in book form and it took two decades before an exhibition of his photographs was arranged.

Despite his apparent contempt for his work, Bourdin still considered himself an artist. Once, when one of his models complained she considered the scene he’d laid out to be pornographic, Bourdin responded by saying “Don’t make me laugh; this is art.” He is said to have thought himself un poète damné, a poet damned to suffer. He continued to paint throughout his career, but his painting seems only to have reinforced his sense of personal inadequacy.

Guy Bourdin died of cancer in 1991. He is considered by many to be one of the best fashion photographers in history. There is no doubt that his approach changed the nature of fashion photography. His use of spectacularly bright color, his decision to make the product incidental to the image, his insistence on controlling the elements of the photograph–those are all to be commended. His misogyny and fascination with death and suffering–those are troubling and disturbing.

The echoes of Bourdin’s work are still resounding in the fashion industry. His work shattered the accepted boundaries of fashion photography and continue to shape the images produced today. The freedom and control experienced by modern fashion photographers is a direct result of Guy Bourdin.

Sex, death, and exquisite shoes. Maybe the next Guy Bourdin will find a way to celebrate the shoes without the misogyny and death.