He eventually became known as the Poet of Prague, a rather grand title for the son of a house painter. Josef Sudek was born in 1896 in the town of Kolin in what was then called Bohemia, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father died when he was two, leaving his mother with two small children and no means of support. The family moved in some of her relatives, an old childless couple who owned a bakery. When he was fifteen, Sudek left for Prague to become a bookbinder’s apprentice. It was during his apprenticeship that he took up photography as a hobby.

Europe in the early 20th century was a cauldron of civil unrest, revolution, and nationalism. It all erupted in June of 1914–what is now called the First World War. In early 1915 Sudek was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army. He continued to shoot photographs during training. A year later he was posted to the Italian front. Sudek described what eventually happened.

“I lost my arm during the eleventh offensive. We were ordered forward and as we charged our own artillery started shelling us…I felt as if a rock hit me in the right shoulder. I started looking around but all the guys who had been standing were now dead.”

His right arm was mutilated; he lost his hand. Because of battlefield conditions, gangrene set in. Eventually Sudek’s entire arm had to be amputated at the shoulder.

Sudek spent the next three years in a variety of hospitals and veteran’s homes recovering from the injury. Despite the loss of his arm, he continued shooting photographs—of the countryside, of the city of Prague, of his fellow patients. He joined the Prague Amateur Photography Club to meet with other photographers. As a wounded veteran, Sudek was given a small pension by the new government (the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved; Bohemia was folded into Czechoslovakia). In 1921 he enrolled in the State School of Graphic Arts in Prague and, for the first time, studied photography seriously as a craft and an art.

After graduating, Sudek was able to supplement his disability pension by shooting some freelance commercial assignments. Despite the grievous nature of his injuries, he made a decent life for himself. He enjoyed his work, he was passionate about music and had enough money to indulge in buying recordings, he traveled a bit (Switzerland, France, Belgium) and followed the newest trends and currents in the art world, he had a diverse circle friends—musicians, fellow war veterans, photographers. He and Jaromir Funke started the Prague Photographic Society, an avant-garde group devoted to moving the craft beyond its traditional limits. Sudek’s life wasn’t perfect, but he appears to have been happy.

In 1926 friends belonging to the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra invited Sudek to accompany them during the orchestra’s Italian tour. He agreed, thinking it would give him a chance to appreciate the beauty of the region—something he hadn’t been able to enjoy when he was in Italy during the war. The first part of the tour went well. But as the orchestra traveled farther south—nearer to the site where Sudek suffered his injury—he began to experience emotional problems. During a concert, he apparently suffered some sort of psychological fugue state and left from the theater.

Sudek’s friends in the orchestra alerted the police, who searched for him without success. He remained missing for about two months before making his way back to Prague. It’s not entirely clear what happened during that period. Sudek’s own account is understandably confused. What he did recall was going in search of his missing arm. “In the dark I got lost,” he said, “but I had to search. Far outside the city toward dawn…I found the place. But my arm wasn’t there—only the poor peasant farmhouse was still standing its place.”

That incident changed Sudek in many ways. He never traveled again. Although he’d make short trips outside the city to photograph the countryside, he refused to leave the environs of Prague. “From that time on, I never went anywhere,” he said, “and I never will. What would I be looking for when I didn’t find what I wanted to find?”

There was also a distinct shift in Sudek’s photography following the 1926 incident. Fewer and fewer people appear in his photographs. There are exceptions, of course, but in general when people appear in his later work, they’re most often seen in the distance, making them indistinguishable as individuals. He would even sometimes pose masks or statues in situations which would normally have called for a living subject.

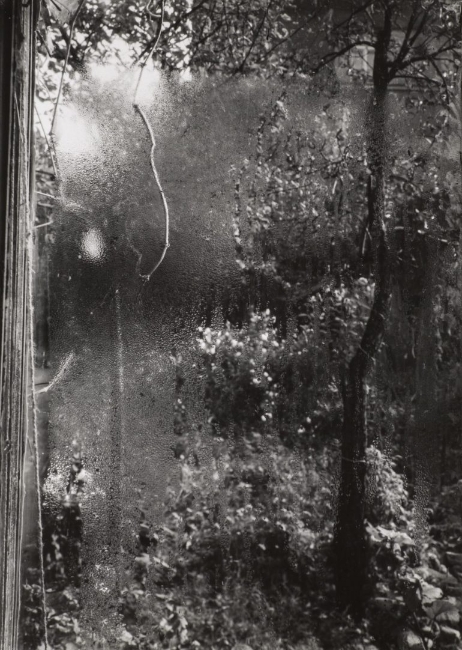

Despite the obvious emotional trauma of those missing months, Sudek began to slowly reconstruct some sort of life. In 1927 he rented a small studio—a wooden shack, really—located in the back yard of a tenement building. There was an old, twisted apple tree and a scattering of horse chestnut trees, which Sudek came to think of as his garden. He would live and work there for the next thirty years.

That same year Sudek joined Družstevní Práce, a cooperative that helped artists, writers, and artisans sell their work. This was critically important because in the following year, 1928, Sudek completed a project he’d begun before his emotional crisis—a series of photographs of the construction of the St. Vitus Cathedral.

Sudek’s work on the cathedral is emblematic of all of his work. It required great patience and persistence—the project took four years to complete, from 1924 to 1928. It took an astonishing amount of foresight—Sudek knew what time of year and what time of day the light would enter a specific window at the precise angle he wanted. In addition, the project reveals the photographer’s passion for light as something more than just a means of illumination. He wanted to portray light as having substance. He was known to set up his bulky view camera in the cathedral, wait for the light to reach the angle he wanted, then he’d rush about waving a cloth to raise dust to give weight to the light.

The cathedral was completed in time for the new nation of Czechoslovakia’s tenth anniversary. With the aid of Družstevní Práce, the artist’s cooperative, Sudek published a monograph of his photographs of St. Vitus. It was an immediate success and Sudek became something of a celebrity.

Sudek’s work from the late 1920s to the late 1930s has generated comparisons to Eugène Atget. Sudek, some critics say, was to Prague what Atget was to Paris. There’s some validity in that assessment in that they were both chroniclers of a great European city. But it’s a facile comparison. Atget worked in obscurity and his images were primarily sociological and documentary. Sudek’s work was distinctly loving and romantic, and he was something of a star in Prague’s artistic circles. He was, after all, the Poet of Prague. It should also be noted that although both Atget and Sudek favored unpopulated cityscapes, they did so for radically different reasons. For Atget, people were a distraction from what he wanted to document. For Sudek, people were apparently a painful reminder of how damaged he was. Even so, I suspect Sudek’s life was more fulfilling than he’d expected it would be.

Then the Nazis came.

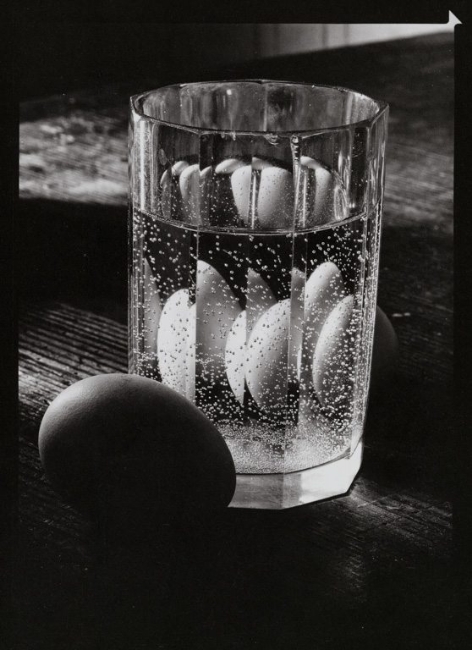

In 1939, as German troops marched into Prague, Sudek retreated into his studio. While Europe—and, indeed, the whole world—once again fell into war, Sudek insulated himself—and his work reflected it. The loving, careful attention to detail he’d given to the city, he now gave to his studio and his ‘garden.’ He shot far fewer landscapes and increasingly became involved in still life images. He experimented more, becoming interested in objects as objects. He also used objects as representations of people. Many of his still life photographs could be described as an homage to the people who gave him the objects in the photograph.

As his work became smaller and more simple, it also began to take on a deeper emotional edge. A piece of fruit on a plate, a glass of water on the windowsill—under Sudek’s lens such simple objects seem to acquire a sort of sobriety and gravitas that’s almost at odds with the buoyancy of the light. “Everything around us, dead or alive, in the eyes of a crazy photographer mysteriously takes on many variations,” Sudek said, “so that a seemingly dead object comes to life through light or by its surroundings.”

When the war ended, Sudek emerged from his studio and returned to his life. In many ways, it was almost as if the war years hadn’t happened. Sudek resumed his place as the Poet of Prague. But it was at least partially an illusion. His photography had become increasingly personal. It was less accessible to the outsider, more about his own perceptions, less about his city, more about himself.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Sudek accrued an avalanche of honors from the city, from the nation, and from the overarching Socialist Republic, as well as from artist’s groups, all which celebrated his body of work. For the first time, however, Sudek’s contemporary work didn’t always receive critical or public success. Following a 1963 exhibit, for example, critics said wrote his work was “too skeptical,” that it was “very fetishistic” or full of “sadness, gloom, dejection, depression.” One wrote he couldn’t “make head or tail of his still lifes, or what they’re supposed to mean.”

Although he was hurt by the critics, Sudek continued to make the sorts of photographs he wanted to make. His early work began to gain the attention of the world’s art communities, and he became still more famous and garnered still more awards and accolades.

By the time of his death in 1976 Sudek was widely recognized as one of Europe’s most influential art photographers. Yet it appears he never considered himself an artist, nor did he think of photography as an art. Photography, he said, “is just a beautiful trade requiring certain taste. It cannot be an art because it is dependent on things that exist without it and apart from it—the world around us.”

The world had been cruel to Josef Sudek. He responded to that cruelty with patience and fortitude and an irrepressible desire to create beauty. It’s something of a miracle that he succeeded.