Larry Burrows arrived in Vietnam in 1962 at the age of thirty-six. He’d been a professional photographer for Life magazine for almost a decade. He’d covered some violent places at violent times (tribal conflict in the Congo, sporadic hostility in the Middle East) and in 1962 Vietnam looked like it would be just another local, low-intensity conflict.

It wasn’t. Burrows would spend much of the next nine years photographing the war in Vietnam. In fact, he would spend the rest of his life covering that war.

Henry Frank Leslie Burrows, born in London in 1926, joined the London bureau of Life magazine in 1942, at the age of sixteen. This was during World War II and Life was arguably one of the most prestigious and important magazines of the era. He worked as an errand boy for the photography department, fetching tea for the photographers and darkroom technicians, drying film, doing whatever odd job was asked of him. Eventually he was allowed to print some of the photographs taken by Life’s war correspondents, including some of the images take by the famous correspondent Robert Capa.

That experience instilled in him a desire to cover conflicts. When the war in Vietnam began to percolate, Burrows was eager to go. In 1963 his first major photo essay on the war in Vietnam was published in Life. It was a 14 page story, the most extensive photographic coverage of that war to date. Unlike the standard reportage coming from Vietnam at that time, Burrows’ images were in color; they were stark and jarring. The photo spread included the above image of an ARVN soldier threatening a suspected Viet Cong with a bayonet.

Burrows’ assignment with Life gave him the luxury of time. Other photographers had to be quick–get into the field, get the photos, get back to the base, process the film, and get the prints to their bureaus as soon as possible so the images could be in the newspapers the following morning. In contrast, Burrows was not subject to a deadline. His landmark 1963 photo essay took six months to complete. As a consequence, Burrows could spend more time in the field with the troops, getting to know them, living with them. That freedom also allowed him to stay with the troops during longer campaigns, covering the full scope of the fighting.

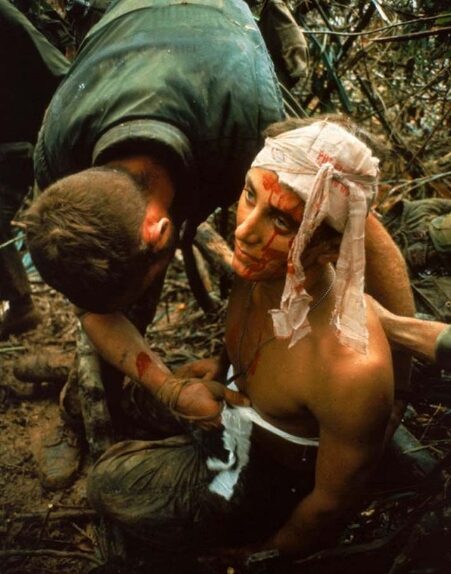

Burrows appeared to be especially drawn to the Marines serving in Vietnam. The Marines had a much-deserved reputation for hard luck–being issued the oldest equipment, getting the worst supplies, getting resupplied less often, finding the worst of the fighting. Burrows stuck with them through the toughest and ugliest of battles. In 1966, he covered Operation Prairie, which included the battle for Hill 484. Marine units, facing an entrenched unit of NVA troops, made numerous assaults on the hill over the course of several days. When it was finally taken, 240 Marines had been killed and more than 1200 wounded. The hill was abandoned soon afterwards (and retaken again three years later at a cost of 17 dead Marines and 125 wounded).

Other photographers sometimes attributed Burrows’ willingness to get in close to the action to his poor eyesight. The risks he took and the long periods of time he spent in the field with combat troops worried his employers at Life magazine. They repeatedly gave him assignments away from Vietnam–photographing the 1964 Olympics in Japan, photographing rare birds in Indonesia in 1965, photographing the bicentennial of the East India Company in 1968, photographing Mother Theresa in Calcutta in 1971. After each assignment, however, Burrows would return to Vietnam.

Unlike some of the photographers who returned often to Vietnam, Burrows wasn’t an adrenaline junkie. He was, instead, determined to cover the war to the end; that was his assignment and he wouldn’t quit until the assignment was finished.

For Burrows, the war ended on February 10, 1971. A helicopter in which he was traveling was hit by anti-aircraft fire near the border of Laos. The chopper was seen to crash in flames, killing the crew, Burrows, and three other photographers (Henri Huet, Kent Potter and Keisaburo Shimamoto). The photograph below was taken by Sergio Ortiz moments before the helicopter lifted off. Burrows was three months short of his forty-fifth birthday. Because of the location of the crash, no attempt was made to recover the bodies.

In March of 1998, a US MIA recovery team in Laos excavated the site of a helicopter crash. The battered body of a Leica M3 and a few bits of broken lenses were all that could be found of Larry Burrows.

Seventy-one journalists and photographers were killed as a direct result of combat during the Vietnam war. Among those killed were Robert Capa, the photographer whose WWII photos had been printed by Burrows in his early days with Life magazine.

In the current conflict in Iraq, 85 journalists and photographers have been killed to date.