In 1979 Joseph Tseng was an under-employed 29 year old freelance magazine photographer living with his sister, Muna, in New York City. On a visit to the city, his parents invited Tseng and his sister to dinner at an upscale tourist-oriented restaurant. The restaurant had a ‘suit and tie’ policy for men; Tseng, unfortunately, only owned one suit coat–a Mao jacket he’d bought at a thrift store. He put on the jacket, strode into the restaurant, and was promptly mistaken by the staff as a visiting dignitary from the People’s Republic of China.

Thus was born The Ambiguous Ambassador. Tseng soon abandoned his Anglicized name and resumed the name (and the traditional form of the name) given to him at birth: Tseng Kwong Chi. He also began a series of self-portraits that would redefine his artistic career.

Tseng was born in Hong Kong in 1950, but grew up in Vancouver. He studied painting and photography in Paris before moving to New York City. There he fell in with an artsy club scene crowd. He shot informal portraits of Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol, among others. But he’s best known for his self portraits.

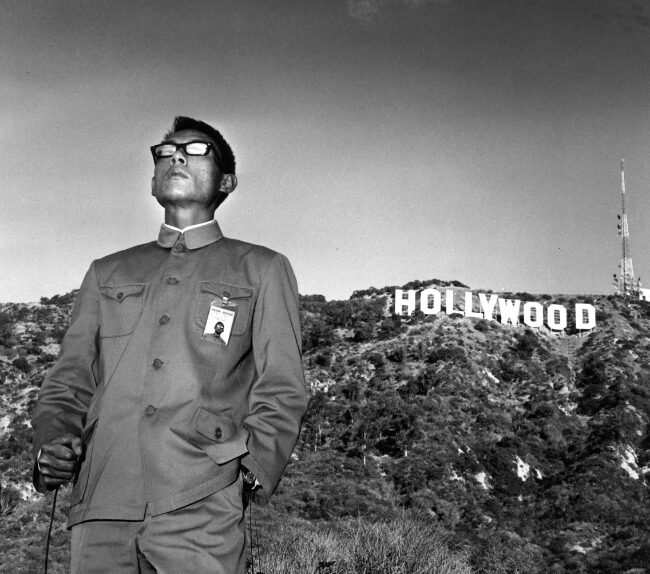

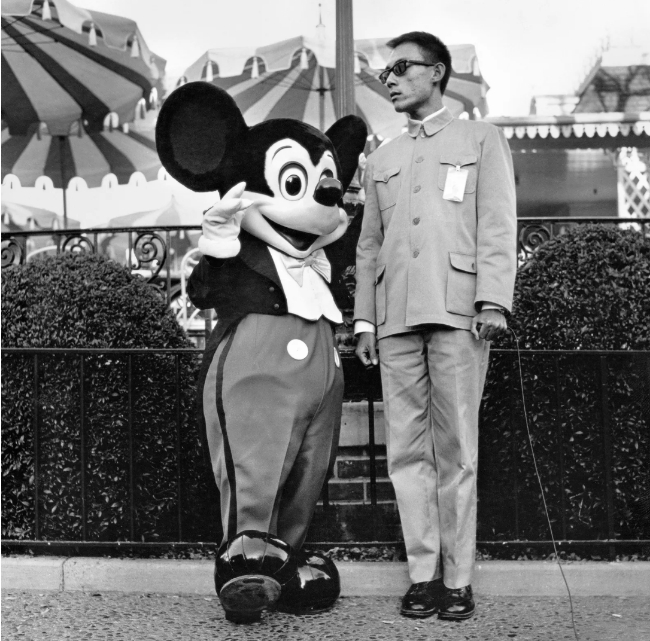

Tseng’s self-portraiture skirts along the border between the serious and the humorous, with occasional forays into the absurd. He generally presents himself dressed in his cheap Mao jacket (or, more precisely, a Zhongshan jacket) and mirrored sunglasses, standing in front of iconic Western tourist attractions or landscapes. His face is expressionless (it’s tempting to call it ‘inscrutable’), his eyes hidden, his posture ridiculously straight and erect. He is the very model of the humorless Maoist bureaucrat.

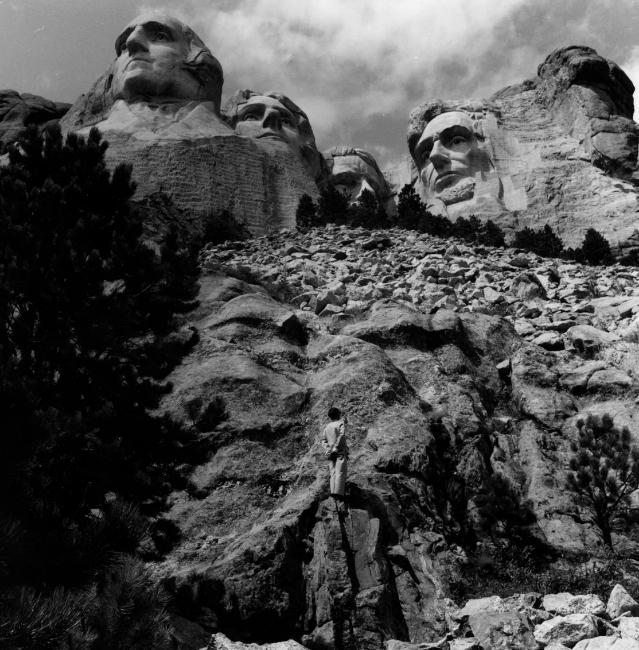

Many of his self-portraits are deliberately composed in the heroic Maoist Cultural Revolution style. There is something of the propaganda poster about them: the giant-sized representative of the proletariat gazing sternly into an egalitarian future. And yet, at the same time, Tseng is mocking that very same idealized vision. His hand is stuck cavalierly in his pocket, he deliberately includes the camera’s cable release in the frame (firmly grasped in a suitably heroic anti-imperialist fist), his visitor’s ID badge identifies him as “SlutforArt.”

The combination of Tseng’s stiff-backed, stony-faced persona and the clichéd portrait setting results in a delightful, cheeky incongruity. He maintained that persona even in situations where his face cannot be seen. In many of his later self-portraits, he can be identified only by his posture–but it is so perfectly distinct that (in context) the viewer cannot fail to recognize the figure in the photograph.

One of the things Tseng discovered in the course of the Ambiguous Ambassador series was that so long as he maintained that posture and that sternly impassive face, strangers would assume he actually was a visitor from the People’s Republic. Even the SlutforArt identification badge (with an ID photo that featured Tseng in the very same outfit, complete with mirrored sunglasses) and the Velvet Underground mirrored sunglasses would be ignored.

In the end, what began as a lark developed into a tongue-in-cheek sociological exploration of the notion of cultural and racial identity. Tseng’s self-portraits aren’t really self-portraits at all. He isn’t photographing himself; he’s not really even photographing that stiff-backed Maoist persona; he’s photographing a very particular and specific concept of social and cultural identity. Tseng discovered that it didn’t matter where he posed or how he posed; in the end, most people didn’t see Joseph Tseng–or even Tseng Kwong Chi. They only saw the Asian face and the Mao jacket.

Sadly, Tseng died of AIDS in 1990.