In 1995 Nick Brandt was in Tanzania directing a music video for Michael Jackson. When the shooting for the video was complete, Brandt took some time off to visit a nearby wildlife preserve. It was apparently one of those pivotal life experiences. A few years later, Brandt was out of the music video business and devoting himself full time to photographing the animals of East Africa.

Brandt’s approach to his work is unique, perhaps because he was never trained as a still photographer. Although he takes photographs of wildlife, he is not a traditional wildlife photographer.

“I’m not interested in creating work that is simply documentary or filled with action and drama, which has been the norm in the photography of animals in the wild. What I am interested in is showing the animals simply in the state of Being.”

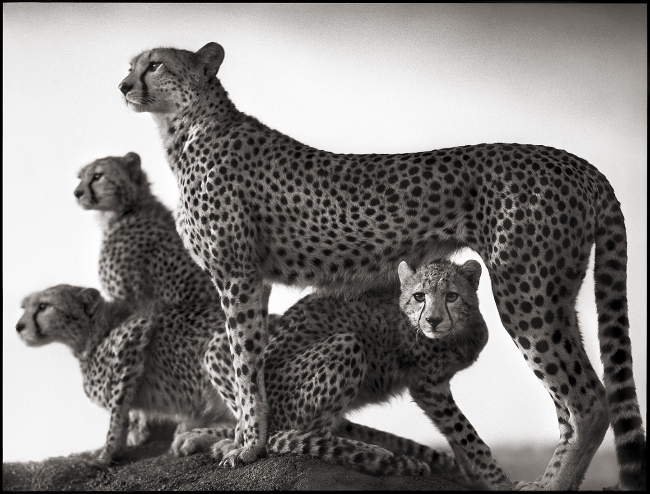

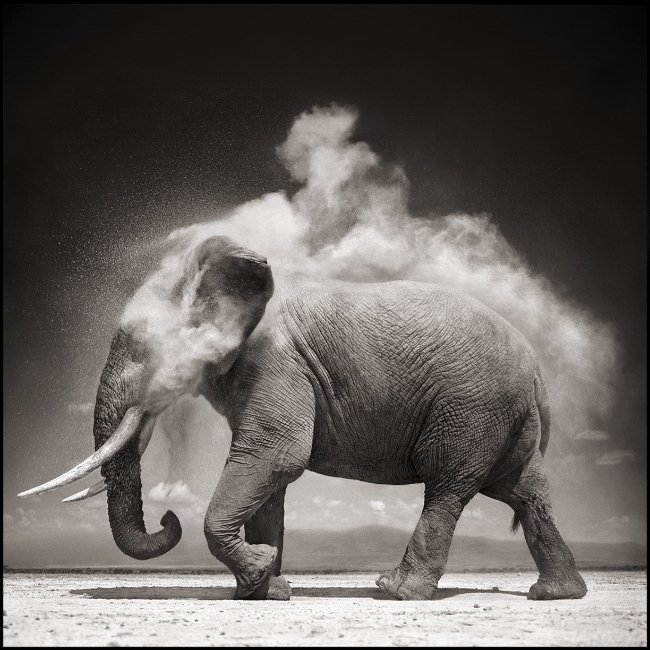

I’m not at all sure what he means by ‘the state of Being’ but it’s clear what interests Brandt is a conceptual view of Africa as an almost mythical place. I’m not sure he has any desire to document the actual lives of real animals in the wild. Instead he creates romanticized images of animals in an equally romanticized setting.

That’s not a criticism; it’s a perfectly valid way of creating art. Any confusion comes from the expectation of the viewer that wildlife photography is somehow meant to document life in the wild. Brandt’s animals are idealized and unabashedly dramatic. They’re almost fabulous in their perfection. Brandt creates these archetypal images deliberately; it is the heart of his art.

Brandt tend to frame his photograph at the extremes–either cinematically wide in composition or almost intimate portrait-like images. He apparently does much of his close work from a vehicle–which sounds contradictory, but actually makes a great deal of sense. It’s not just for safety reasons, but because the animals in wildlife preserves are accustomed to the presence of vehicles; they’d run away from a human on foot.

He uses a Pentax 6X7 camera and only a few fast prime lenses (75mm, 105mm, 150mm and occasionally a 200mm). Those lenses allow him to get the narrow depth of field he finds so attractive. He generally shoots in black and white, which is unusual for wildlife photography. He frequently uses a heavy neutral density filter and often a red filter to darken the sky. Brandt claims he does very little photoshop manipulation of the image other than his signature vignetting and occasional adjustments to contrast and tint. Most of the unusual effects he obtains are, he says, created by trying odd things with the camera.

“I work in a very very impractical way – very manually – and lose a crazy number of potentially great shots with all the faffing around I do. But I do it because occasionally something great comes out of such impractical methods.”

A lot of wildlife and nature photographers have criticized Brandt. They call his work unrealistic, they claim he manipulates his images more than he admits, they say his images are sentimental, they say there is nothing natural about his view of nature.

And in many ways, they’re absolutely right. Brandt’s photographs aren’t about nature at all. They’re not about real life. They are about depicting these animals as they exist in the minds of people throughout the world. Nick Brandt isn’t so much photographing animals as they exist; he’s photographing animals as we wish they existed. That’s his art.