I have to admit, I was first attracted to Lili Almog by her name. It’s just immense fun to say out loud. People who are much more aware of the photographic art world, though, have been drawn in by her images of women in their private spaces.

Born in Tel Aviv in 1961, Almog emigrated to the United States in the mid-1980s. She worked for a couple of years as a photojournalist before earning a BFA from the School of Visual Arts and turning to fine art photography. Almost immediately, she chose to concentrate her work on women and the lives they lead. Her work, she says:

focuses on creating representations of the feminine body and psyche. I try to capture the cultural and spiritual identity of women set in their private spaces. My images combine elements of history, social class, and personal experience in surroundings that have timely significance.

Almog has created three major studies concentrating on the intimate lives of women. The first, Bedroom Series was a three year examination of women in their bed chambers (hence the clever title). Bedrooms, she said, were sanctuaries in which women could most often be themselves. They remove their clothes, remove their make-up, remove their public faces. She followed that series with a set of portraits of Korean women in a New York City mogyoktang, a bathhouse.

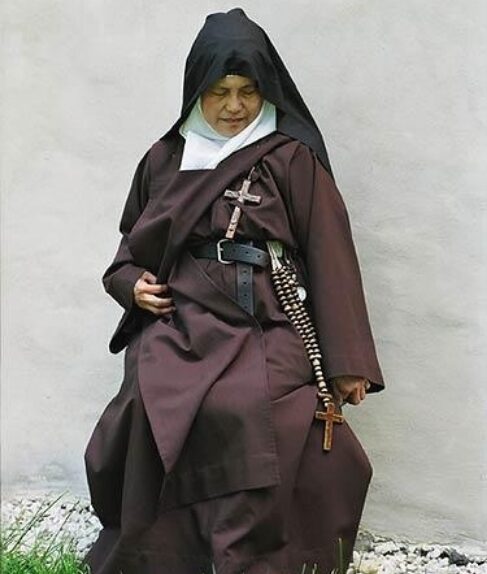

I’ve chosen to concentrate on her most recent series, entitled Perfect Intimacy. The subjects were nuns from three different Carmelite convents.

The origin of the Carmelite Sisters dates back to the 15th Century. They’re a cloistered, contemplative order. The nuns isolate themselves in order to devote themselves more fully to prayer and devotion. Although they are detached from the outside world (and, to a large extent, from the material world), they aren’t anti-social. The concept of community is a critical aspect of their lives.

To get these photographs Almog spent time in three different Carmelite convents: at Port Tobacco, Maryland (the first Carmelite convent in the U.S., founded in 1790), at Bethlehem in Palestine (founded in 1875), and at the original convent on Mt. Carmel in Haifa (founded in the 12th Century). As a Jew born in Tel Aviv, Almog had never been inside a church. She was also the first Jew to sleep in each of those convents. That “outsider’s eye” gave her a fresh perspective on her subjects.

Where her earlier works had focused on small women-centered havens–bedrooms and a bath-house–her Carmelite series allowed her to see women in community, and a community that has deliberately set itself apart from the world of men and most worldly concerns. She had expected to find a supportive community; it seems she did not expect to find a community quite so merry and joyful.

I realized they had this intimate relationship with God, with Christ—their husband—and this love, this kind of relationship with an abstract person, for me, it’s almost like [a] perfect intimate relationship.”

Initially Almog reported she had some difficulty in getting photographs. She was housed in the guest quarters; the nuns had no reason to enter the guest quarters. So Almog began to attend the main chapel in order to be with them as they prayed. It was as she observed them praying that she decided on the title of the project: Perfect Intimacy.

Almog was very respectful of the wishes of the nuns. Rather that attempting to photograph them unaware, going about their daily business, she allowed the nuns themselves to determine when and how she could photograph them. She said,

Sometimes they would say, “Oh, don’t take a picture of me,” because she was in an apron or something. They always wanted to look good, too, even though they are nuns. For me, it was like, okay, this is your stage, you play it the way you want to. It’s fine. I’ll get you the way you want me to get you.

Almog has described her work as primarily being about the representation of women by a woman. She’s not attempting to unmask something hidden behind a curtain so much as she is attempting to reveal the way women perceive themselves when they’re in their most secure settings. She describes the convents she visited as “almost like a utopia of a women-run society.”

In a sense, Almog’s photographs could be said to have adopted a Carmelite habit. They are quiet images, simple, humble, perhaps even chaste, with a limited palette of colors. The women in the photographs are often faceless, not just anonymous but indistinguishable. And yet something of their personalities somehow finds its way out.