NUDE IMAGE NUDE IMAGE NUDE IMAGE

Who can say where it all began? Perhaps with the Gibson Girl, often called the ‘ideal’ woman of the 1900s. Or maybe it was Paul Chabas’ famous 1912 painting September Morn, which was used on calendars and window displays and to advertise everything from cigars to candy. Or maybe it can be traced even farther back to the posters of Henri Toulouse-Latrec.

Whenever it began, the style of imagery wasn’t named until shortly after the First World War, when some unknown wag referred to a risqué photograph of a woman as being “sweeter than cheesecake.” Cheesecake pictures (which later morphed into pin-up pictures) are mass-produced images featuring scantily clad or partially nude women–usually ‘wholesome’ looking women–in poses that are provocative without being overtly sexual. The heyday of cheesecake began during the Second World War and reached its high water mark during the 1950s.

Linnea Eleanor Yeager was born in a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1930. As a teenager she was an avid fan of movie magazines, and would practice glamour poses in the privacy of her room. She picked up the nickname Bunny after playing the Easter Bunny in a school play. Her parents moved to Florida when she was 17. After she graduated high school, Yeager enrolled in the Coronet Modeling School, and began to enter beauty contests. At various points, she was the Florida Orchid Queen, Miss Trailercoach of Dade County, Queen of the Sports Carnival, and the Cheesecake Queen of 1951.

She became a top ‘swimsuit’ and cheesecake model. When Yeager discovered photographers made more money than their models, she began taking evening classes in photography. Before long, she ceased to be a successful cheesecake model and became a successful cheesecake photographer.

Yeager’s work is solidly within the parameters of the traditional cheesecake photography. For the most part, she made pictures of cheerful, attractive young women who looked like “the girl next door.” Yeager has described her models as “young girls” who were “certainly desirable, but not threatening to any man’s ego.”

Yeager not only shot the photographs, she also created many of the costumes her models wore–and they were costumes. The bikinis, the leopard skin tunics, the negligees and the body suits weren’t meant to be worn by ordinary people in ordinary circumstances; they were props. That was perfectly in keeping with the entire concept of cheesecake. The genre isn’t grounded in reality. It’s not even really about honest sexuality. The idea behind cheesecake was to create a sort of safe, tidy, mildly naughty fantasy. It’s sexuality without sex. Cheesecake is intended to titillate, not excite.

Yeager was also one of the first cheesecake photographers to abandon the studio and shoot models outside, using natural light. Because of that, she was also one of the pioneers of fill flash, used to reduce shadows when shooting in bright Miami sun.

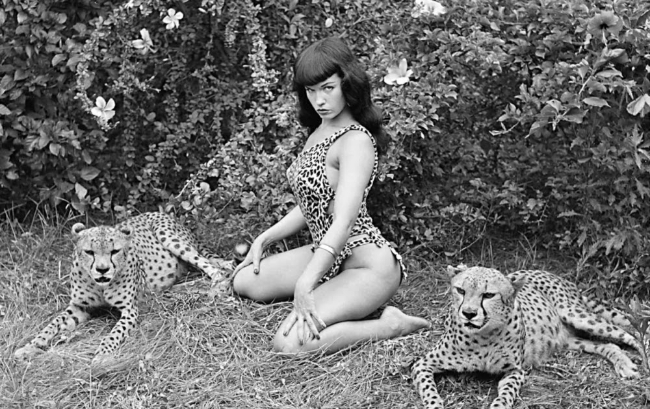

Despite her success as a cheesecake photographer, Bunny Yeager is probably best known for her ‘discovery’ of the iconic model, Bettie Page. Page had, in fact, been modeling for various ‘camera clubs’ for half a decade by the time Bunny Yeager met her in the mid-1950s. Yeager, however, arranged the two photo shoots that turned Page from a minor model into a cheesecake superstar. She first photographed Page at a wildlife park, posed with a pair of cheetahs. Yeager shot two sets of photos at that session, a common practice in the age of cheesecake; in one set Page was dressed in a leopard-skin bikini; in the second set, she was nude. The “Jungle Bettie” photos were wildly popular among cheesecake fans.

The real breakthrough–both for Yeager and Page–took place in the second shoot. Yeager wanted to create a photograph for a cheesecake calendar. She posed Page nude, wearing only a Santa Claus hat, on her knees, decorating a Christmas tree. While the photographs were being developed, Yeager noticed a new magazine at a newstand–Playboy. Instead of sending the images to the calendar publisher, Yeager sent them to Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner. Yeager’s photo of Bettie Page became the magazine’s first holiday centerfold.

Yeager’s experience as a model helped inform her approach to taking photographs. Because she was a woman, her models were often more comfortable and relaxed during their photo sessions. Yeager also brought a flair for costuming to the genre, which made the images more playful. All these factors played a role in her success.

It has to be admitted that Bunny Yeager’s work wasn’t technically or artistically superior to that of other cheesecake photographers. What set Yeager apart was her gender and a genius for self-promotion. She gave herself the label of “The World’s Prettiest Photographer” and hyped herself relentlessly. When approached with the idea of writing a book about photographing women, Yeager agreed. Photographing The Female Figure was the first of her 24 photography books.

As she became better known, Yeager extended her photographic practice beyond cheesecake photography. She did photo shoots for venues more mainstream than Playboy, magazines like Redbook, Women’s Wear Daily, and Cosmopolitan. Perhaps her best-known photograph is of the actress Ursula Andress, emerging from the water in a white bikini in Jamaica for the 1962 James Bond film Dr. No.

People will obviously disagree about whether or not cheesecake is art. There is no doubt, however, that cheesecake photography as it was practiced in from the 1940s to the mid-1960s was a significant form of popular American culture. During and immediately after the horrors of the Second World War, the photos depicted clean, healthy, vivacious, cheerful young women–a sort of safe, idealized sexuality that could only exist in the fantasy of grizzled soldiers. This continued into the increasingly grim Cold War. Nobody wanted reality; they wanted a respite from reality. They wanted an uncomplicated world. A world that might be a little naughty, but would remain essentially uncorrupted. And cheesecake gave it to them.

But, of course, it couldn’t last. It’s no coincidence that cheesecake as a genre largely died out in the late 1960s-early 1970s, during the period of the Vietnam War. It was replaced by magazines offering more explicit and graphic depictions of women, which Yeager found distasteful.

“They had girls showing more than they should. The kind of photographs [magazines] wanted was something I wasn’t prepared to do.”

By the mid-to-late 1970s, Yeager had largely abandoned photography. Her work, however, continues to be sought after by collectors.