“Perhaps it’s good for one to suffer,” said Aldous Huxley. He asked “Can an artist do anything if he’s happy? Would he ever want to do anything? What is art, after all, but a protest against the horrible inclemency of life?“

I can’t entirely agree with Huxley, but it can’t be denied that a lot of very good art has been created out of–or accompanied by–misery. Emotional misery, physical misery, spiritual misery; in some ways, the origins of the artist’s anguish is less important than the reality of its existence. The source of photographer Ursula Sokolowska’s misery is her childhood. That misery both forms and informs her work, and it does so directly and indirectly. It’s most obvious in her series entitled The Constructed Family.

Sokolowska was born in Krakow, Poland in 1979. She and her family immigrated to the U.S. when she was a child. She has described her childhood as traumatic, though she doesn’t characterize the actual nature of the trauma (and perhaps that’s just as well). She’s quite clear, however, that it was family-related. Certainly whatever trauma she experienced would likely have been compounded by being an immigrant child.

In her Constructed Family series, Sokolowska creates scenarios in which malformed children are situated in dark, menacing circumstances. The children are, for the most part, isolated and alone. Even when adult figures are present in the photographs, there is an unsettling and unbalanced quality to them.

The child figures themselves are faceless dolls constructed by Sokolowska. Using slides from old family photographs she projects faces onto the dolls. The faces are hers, as well of those of her brother and parents. These are not the typical dolls of the child’s playroom; these are the sorts of dolls that creep out of the dark closet after midnight, with knives, accompanied by soft, depraved giggling.

For the most part, Sokolowska uses the same processes in her other photographic series. The series generally have the same motivation: they grow out of her personal emotional situation. She uses the same general technique of projecting an image onto a three-dimensional model. The human models and/or the projected images are generally drawn from the same pool: members of her family or her close friends. And the images usually share the same dark, fragmented feeling.

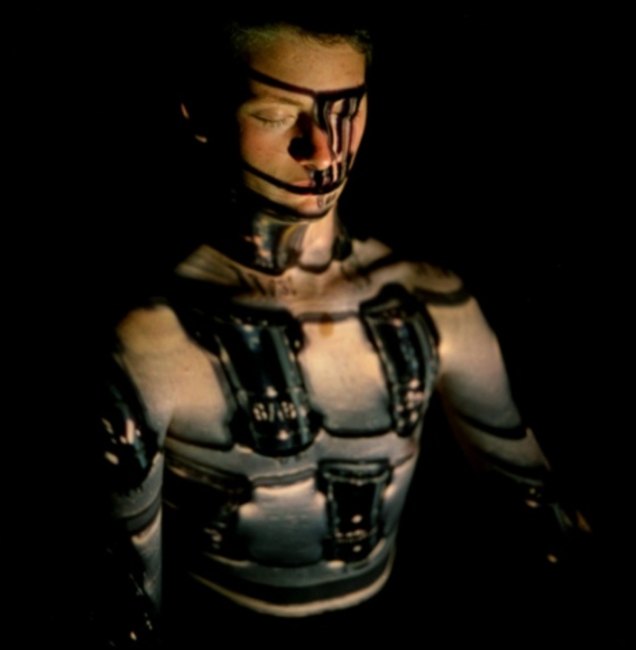

In her series Automata Sokolowska projects blocks of color and geometric patterns onto her brother, presenting him in a way that occasionally seems robotic. By treating him as a blank, passive canvas on which she imposes her art, she is (or at least claims she is) making a statement about how the individual is defined, molded, even controlled by external events and conditions. The concept is both clever and meaningful. Although I’m not entirely convinced these images actually address the concept, the images are nonetheless very compelling.

In a more recent and untitled series, Sokolowska delves into the art of the grotesque. This ancient art form dates back to the Roman era. It involves elaborate constructs of animals or human beings created out of anatomical impossibilities and improbabilities. Sokolowska’s work is a sort of modern interpretation of the paintings of the 16th century artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo (an example of whose work can be seen here).

She projects images of plants and flowers onto the faces of her friends, turning them into surreal objects of fantasy. The images are both strangely delicate and deeply disturbing, as well as incredibly lovely.

Like so many contemporary artists, however, Sokolowska tends to further obscure her work by describing it in bizarrely heightened language that is opaque and (in my opinion) often meaningless. Of her Untitled series, she writes:

“These images pose several questions towards the societal view of gender as related to the biological roles that exist. By using the flower as the reference point, we see the inequality and the taint that is applied to a supposedly natural and beautiful inevitability. These human plantlife carry their own baggage that spews out of every orifice and drops moistly from their painted skin.”

Sokolowska’s work is so compelling that I can forgive her for the appalling tripe she writes about it. The work succeeds entirely on its own.

There is an almost granular quality to the emotional trauma displayed in Sokolowsa’s photography. Tiny particles of her uncertainty and agonizing insecurity filter out through her images and get stuck in our own psyche. Looking at her work is like visiting to a nightmare beach; you inevitably bring back sand with you and it will trickle out your shoes and towels unexpectedly for weeks afterwards. And yet you always want to go back to that beach again.

I’m still not convinced Huxley is right. I don’t know if Ursula Sokolowska would have created such powerful work if she’d had a happy childhood. But I think it’s safe to say she would not have created work like this.