In the late 1950s when director Federico Fellini was writing the screenplay for his classic movie La Dolce Vita he needed a name for a character–a news photographer. He chose the name Paparazzo.

Where did he get that name? One etymologist says Fellini claimed it was the nickname of a childhood friend and that paparazzo was Calabrian slang for a particularly noisy and irritating mosquito. Another says paparazzo means “sparrow” and that Fellini chose the name because he thought the press photographers fluttering around celebrities looked like little hungry birds. Yet another claims Fellini took the name from a Greek innkeeper in Calabria called Coriolano Paparazzo, whose surname was originally Papasaratsis (which apparently translates as “priest-saddlemaker”).

Regardless of the origin of the character’s name, it stuck. After the release of La Dolce Vita candid celebrity photographers became known collectively as paparazzi. In the U.S. the pre-eminent paparazzi was, without question, Ron Galella.

Galella was born in the Bronx in 1931, the son of an immigrant coffin-maker. While serving in the Air Force during the Korean War (1950-53), he was trained as a photographer, both on the ground and in the air. When the war ended and he was released from active duty, Galella attended the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles, where he studied photojournalism. When he returned to New York City, Galella discovered a ready source of income almost on his doorstep. New York City is, of course, the home of many celebrities (and far more would-be celebrities). Galella discovered he could earn money as a freelance photographer, shooting candid, unguarded images of famous people.

At that time celebrities generally posed for publicity shots, which were commonly taken at scheduled public events–openings of shows, when they arrived or departed from town, at balls and parties. They expected their photographs to be taken, and they would stop at a certain spot and allow the photographers to snap away. There was an unspoken arrangement between celebrities and photographers; the former would pose, the latter would shoot the pose. Galella ignored the arrangement; he photographed celebrities engaged in the ordinary aspects of life–going to the gym, shopping, walking the dog, dining in a restaurant. He photographed them in ordinary clothes, without make-up, in situations that were not glamorous. He photographed them without their permission, and often without their knowledge.

“I think [celebrities] are interesting people. It’s, I don’t know, their glamour, charisma, or something. We all have this curiosity…is Liz Taylor as glamorous as she is portrayed on the screen? I try to show that they’re human beings, that they’re common people doing common things.”

Fan magazines like Photoplay and Modern Screen eagerly bought his work. Tabloids like The National Enquirer paid him large sums of money for capturing the unguarded moments of the rich and famous. By the late 1950s, Ron Galella had become the premier celebrity photographer in the United States. By the mid-1960s, and for the next twenty years, his life was spent almost entirely in New York, Las Vegas and Hollywood.

Celebrities, of course, have a love-hate relationship with the paparazzi. In the early stages of their careers, many aspiring actors and models feel they need the exposure and they actively seek it out. As their careers become more established, they necessarily become more protective of their privacy and the way they’re portrayed in the popular press. They still want the attention; they just want to have control over it. As their careers begin to wane, many often try to cling to fame by once again courting the paparazzi.

The paparazzi have a totally different agenda. For them, it’s about the money and, to some extent, about the excitement of the chase. They’re after the shot that will bring in the big paycheck. Those shots are, almost by definition, the shots celebrities are most desperate to avoid.

In any event, there can be no doubt that being unable to move about freely without somebody photographing your every step has to be exceedingly annoying and frustrating. Of his work, Galella said:

“My job is thick with risks, threats, occasional violence and sometimes the necessary folly that courts humiliation and ridicule.”

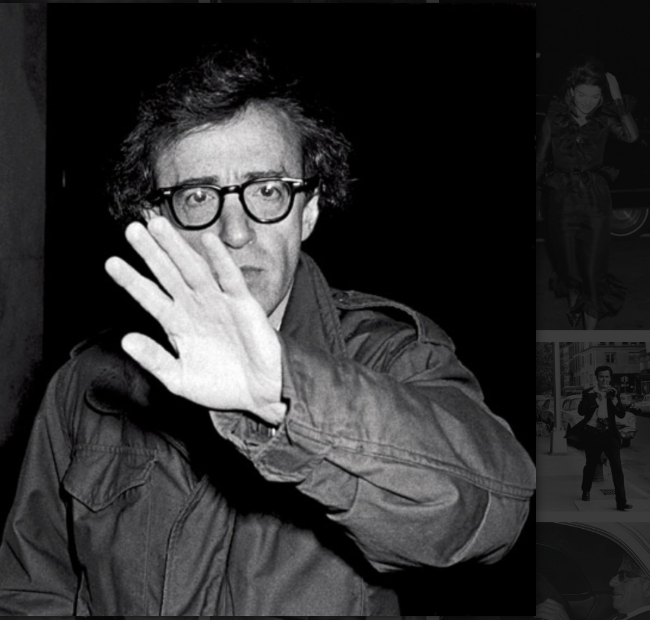

He has experienced the humiliation, the ridicule and the violence. Brigitte Bardot had her friends turn a hose on him. Jackie Kennedy Onassis took him to court and got a restraining order requiring him to stay at least fifty yards away from her. Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, in vacation in Mexico, had their bodyguards rough him up and then had him arrested by the Mexican police. Marlon Brando did the rough work himself, pummeling Galella on a Chinatown street, breaking his jaw and knocking out four of his teeth. Thereafter, Galella wore a football helmet when he photographed Brando.

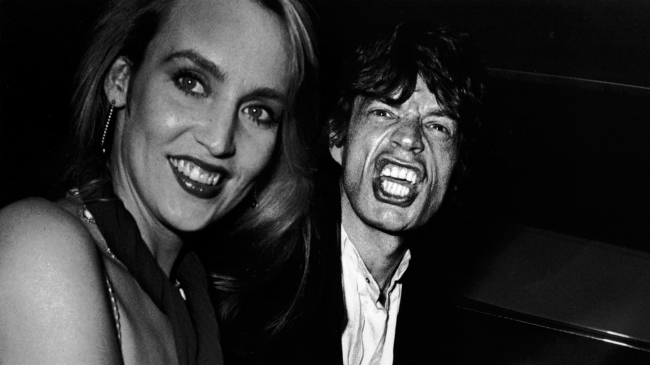

Despite the anger and resentment of many celebrities, Galella increasingly found himself invited to attend fashionable parties and events. The reason appears to be that Galella had the uncanny knack of taking photographs that were candid and unscripted but that somehow lent an air of glamour to his subjects. It might, in some cases, be a dissolute sort of glamour, but it was glamour nonetheless. And glamour is a large part of the appeal of celebrity, both for the fans and for the celebrities themselves.

Galella is largely retired now. He spends much of his time organizing and digitizing his photographs. His work is now being sold in galleries.

Oddly enough, Galella has little respect for modern paparazzi. His job, as he saw it, was to show the rich and talented and famous as they really were when they weren’t on the public stage.

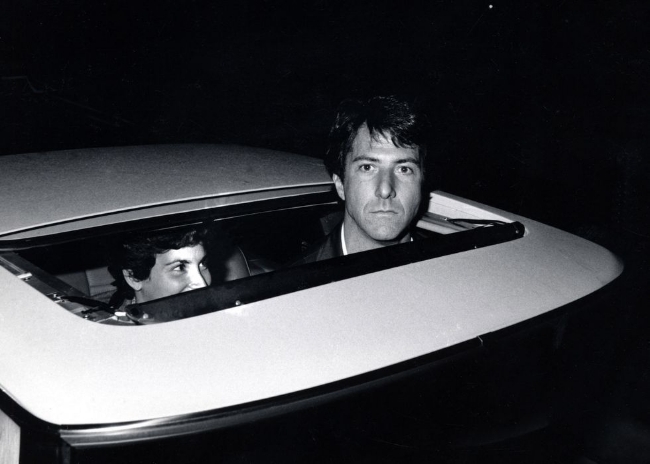

“My whole idea was to hide and catch the real stars just being themselves. I never told Dustin Hoffman to walk his dog.”

He complains that the new generation of paparazzi are either lapdogs of publicists and complicit in creating celebrities whose only claim to fame is their celebrity, or they want to take a photo that can damage or end a celebrity’s career/reputation.

It would be difficult to defend Galella’s ethics–or the ethics of the paparazzi who’ve followed him–and I wouldn’t want to try. But when a photographer can get paid a few thousand dollars for a candid photograph of Paris Hilton doing something embarrassing, or half a million dollars for a photo of Anna Nicole Smith’s body being wheeled out on a stretcher, but only a few hundred dollars for a photo of a child dying of AIDS in Africa or a flood victim in Texas, it’s not surprising that the paparazzi are flourishing.