Every few years the world of art photography discovers a new golden child. From 2000 to 2005 the golden child was Ryan McGinley. He was young, he was gay, he was a skateboard thrasher, and he had moderately attractive friends who got high and were willing to pose nude. All that gave him street cred, and McGinley converted that cred into a career. If that career has slowed down somewhat since 2005, it’s still ticking along at a rapid pace.

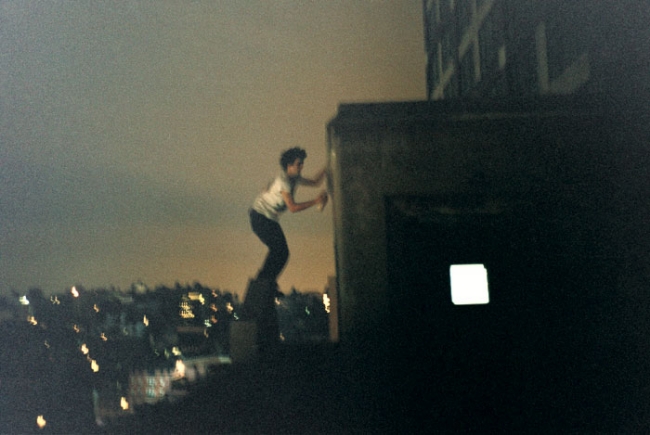

In 1999 McGinley was a nineteen year old student at the Parson’s School of Design in New York City. Using his home computer, he put together a small book of fifty of his photographs, gave it the title The Kids are Alright (apparently from the song of the same name by the Who), and sent it to a hundred magazine editors and well-known New York photographers. The photographs were of his friends doing the things New York party kids did: drugs, sex, dancing, shoplifting, hanging out, vomiting, skateboarding, tagging structures.

The self-published book struck some sort of cultural chord. The editors at Index magazine were so impressed they immediately offered him an assignment in Berlin. McGinley soon drew assignments from such magazines as Vice, Butt, Dazed and Confused and The Fader. But within a couple of years he was also shooting for the New York Times Magazine, and doing advertising work for Puma, Nike, Verizon and other corporations. He photographed supermodel Kate Moss. At the same time, his work was appearing in hip galleries in New York City. Then, at the age of 25, Ryan McGinley became the youngest photographer to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum.

He was the golden child and he was everywhere.

Both his commercial and personal photography followed the same theme played out in The Kids are Alright. He continued to shoot young, aggressively hip men and women engaged in play–often in the nude. However, his process changed. His original images were primarily documentary photographs of spontaneous behavior, but with success McGinley began to take a more directorial role.

Instead of shooting the things his friends did, McGinley began to create semi-controlled scenes. He would, for example, rent a house in the Vermont woods and invite his friends to stay for a week during which he would photograph them. Everybody understood they were there to be photographed and to engage in photographable behavior.

McGinley described his process to an interviewer:

“I’ll usually start with a rough idea, like how pretty it would be to have a whole tangle of naked people really high up in a tree. Then I’ll find a location, get everyone together and tell the general plan but let everyone be spontaneous, within that controlled environment.”

More recently McGinley has been taking his show on the road, leaving New York City behind and driving cross country, shooting photographs all the way.

A number of famous photographers have crossed the United States, photographing their friends and the people and places they encountered. Robert Frank did it in the 1950s, Larry Clark did it in the late 60s, and it’s become almost a tradition. Unlike Frank and Clark, however, McGinley’s excursions aren’t entirely spontaneous.

The preparation for the cross country trips begins months in advance. McGinley’s interns select 100 candidates from a group of volunteers–local musicians, aspiring models, acting students, photography students. McGinley interviews the chosen 100 and selects twelve to fifteen, chosen for their looks and for “mellowness and strong personalities.” These chosen few join the road trip in two separate shifts. Two vans are used to carry the models and photographer as they travel. Four assistants accompany them to deal with props (trampolines, fireworks, etc.) and provide the music to set the mood.

As they travel McGinley finds a setting or location he likes, suggests a general approach, then sets his models loose–again, usually nude (in one of the vans is a sign saying CAN I RIDE NUDE ON YOUR MOTORCYCLE? that the models show to passing motorcyclists). The resulting photographs have the same energy as his earliest work, though without the rough and raw edges.

Not surprisingly, there has been an anti-McGinley backlash in art photography circles. He is criticized for a variety of sins ranging from his use of androgynous models celebrating a certain type of youthful beauty to outright fraud for creating ‘controlled spontaneity.’ An article about McGinley in Slate magazine was subtitled Does photography’s hot young thing deserve all the hype? His work has been called MySpace photography. Unflattering comparisons have been made with other so-called “lifestyle” photographers, like Wolfgang Tillmans, Nan Goldin or Larry Clark.

There is certainly some validity to the criticism. The young junkies and speed-shooting cowboys of Larry Clark’s work weren’t posing for the camera; their lives were bleak and grim and some of them died. When Nan Goldin photographed herself with a black eye, it was from a beating she received from her heroin-using lover. McGinley photographs at least two of his models with black eyes (including one seen above), but they are smiling and pretty and playful. McGinley’s critics say he is attempting to show lives devoid of consequences, where sexuality is just innocent fun, where there is no guilt or shame, where drugs are just part of the youthful hijinks and nobody is unhappy for very long.

McGinley doesn’t entirely disagree with that analysis. “I am absolutely not interested in making depressing images,” he says. About his road photographs, he says this:

“People still take photographs as truth. They look at them and think what they see really happened and while it did really happen, it didn’t really happen like that. It is more like pseudo-fiction because it did happen but it might not have happened if it weren’t going to become a photograph.”

Ryan McGinley’s more recent work isn’t about reality. It’s about fantasy.

Some of the glow has gone off the golden child, but he still works steadily, gets paid large sums of money and receives artistic accolades. McGinley was recently named Young Photographer of the Year by the International Center of Photography.

Does he deserve all the hype? I don’t know. Does the fact that there is little to distinguish between his photographs for the gallery and his photographs for Nike mean his work is plastic? Or does it mean his vision is consistent and he shoots the same for everybody? I don’t know. Does the fact that he uses models rather than ordinary people and that he picks their settings mean their behavior is less spontaneous? I don’t know.

I do know that some of his photographs are remarkably beautiful and engaging. Maybe that’s enough.