Ralph Meatyard was one of those WTF photographers. That’s not an actual genre of photography, but perhaps it should be. Images that force the viewer to experience a variety of contradictory emotions, that leave the viewer thrilled, a little bit uncomfortable, confused, and eager to see more.

It seems weirdly appropriate that despite the creative grotesquerie of his work, Meatyard was born in Normal, Illinois. It’s deliciously ironic that the photographer known for strange, uncanny images was the father of three, the president of his local Parent-Teacher Association, and the coach of a Little League baseball team. And it’s wonderful in the strictest sense of the term that he was essentially a weekend photographer who earned his living as an optician.

He was born in 1925. After a tour in the Navy, Meatyard settled down in Lexington, Kentucky. He took a job with an optical firm that also developed optics for camera equipment. He got married, had a child, and bought a camera in 1950 to photograph that child. In 1954 he joined a local camera club. He was soon shooting unusual portraits of his kids.

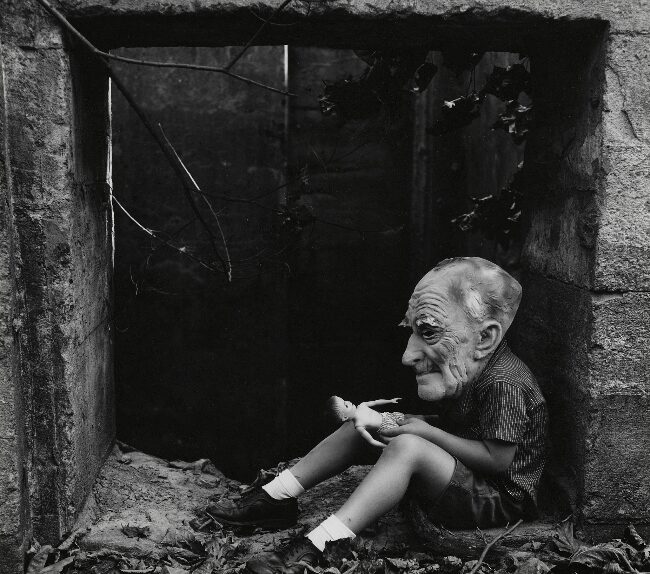

Meatyard was just getting started. In 1958, he and one of his sons walked into a Woolworth’s Department Store. I assume it must have been near Halloween, because Meatyard left that store with a shopping bag full of cheap latex masks.

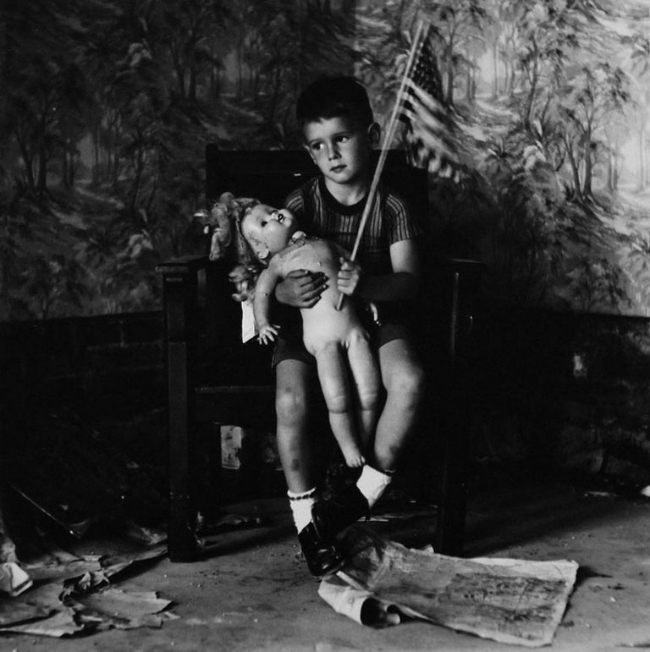

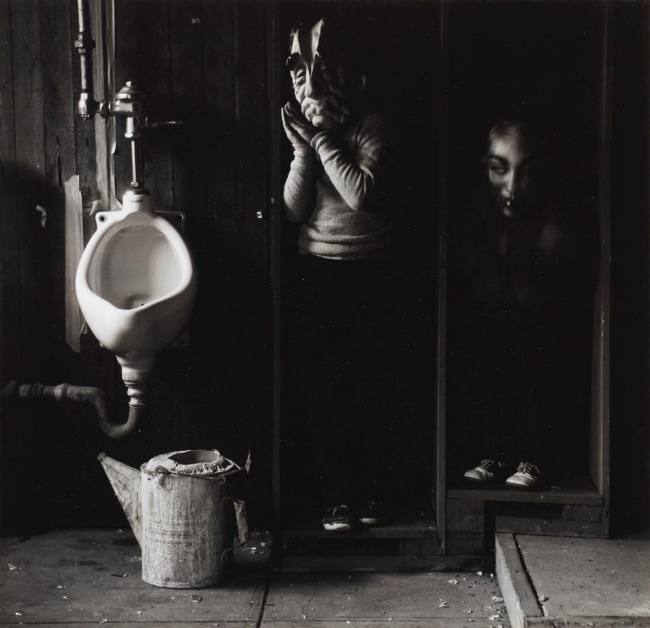

The masks sort of set him free as a photographer. Meatyard abandoned the notion of traditional portraiture and developed a style that depended heavily on setting, pose, and blatant artifice. And yet his work still gave the impression of being spontaneous. He began creating images that were strange, eerie, sometimes nightmarishly disturbing, sometimes quivering with anxiety. The fact that many of his subjects were children–his own children–only heightens the weirdness and gives the images a sense of foreboding.

This works in large part because Meatyard never tries to present these masks or masked characters as anything other than what they are; he’s not attempting to disguise anything. He’s simply inserting another element of the macabre into the frame.

The late 1950s and early 1960s in the U.S. saw the rise of the Beat Generation, which had a significant influence in Meatyard’s work. Through the Beat movement he was introduced to the concepts of Zen Buddhism, including the acceptance of the impermanence of life. A near-fatal heart attack in 1961 apparently reinforced Meatyard’s understanding of that concept. A suggestion of spirituality–often a grim and gloomy spirituality–began to appear in much of his work.

Meatyard’s photographs had always featured dark spaces–rich, black, inky spaces that hinted at something outside or beyond the viewer’s ability to see. After his heart attack, those tenebrous spaces began to be inhabited by murky figures, figures that sometimes seem materialize out of the darkness. These figures not only heighten the aura of uneasiness but they seem to emphasize the intimation of inevitable mortality. By combining those spooky figures with the innocence of children, the image’s chemistry becomes almost combustible.

Meatyard often liked to include a bit of motion in his photographs, a bit of intentional blur. Sometimes he’d deliberately jiggle the camera a tad when releasing the shutter, sometimes he’d have the subject move. These last photos were generally more effective. The blurred subject often seems to be in transition, though changing from what and to what remains a mystery.

Mystery is at the heart of Meatyards work. These are weirdly complex images revealing weird and contradictory emotions. One critic wrote that Meatyard’s best photographs resembled “short stories that have never been written.” There is an odd literary feel to his work. There is no narrative there, of course, but in his best work there is the hint of being in a critical scene of an interrupted narrative. Something is happening in these photographs, something pivotal but not entirely unexpected.

Despite being influenced by the Beat generation, despite the impact of his literary friends, Ralph Meatyard was distinctly not a hip sort of guy. He remained a working optician who owned a store that sold eyeglasses, a weekend photographer, and husband and father out of the Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood mold. On those weekends, though, Meatyard became something extraordinary. On those weekends he became the Indiana Jones of the photography world, exploring the dark and hidden catacombs of the human psyche.

In 1970 Meatyard was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He died in 1972, a week before his 47th birthday.