NUDES NUDES NUDES

Australian photographer Vee Speers has said, “I didn’t choose photography, it chose me.” Although that’s clearly artistic blather, it’s still revealing. At the age of ten her father let her borrow his Voigtlander camera, and she developed and printed her own photographs in a darkroom her father had bodged together in an old camper/caravan parked in the yard.

She drifted away from photography and spent a few years exploring other artistic media. While attending the Queensland College of Art she rediscovered photography and fell back in love with the medium. After graduation she spent half a year as a photographer for ABC Radio and Television in Sydney, shooting publicity stills of actors and celebrities. In a way, even at that point in her career she was photographing masks and hidden lives.

Then, in 1990, she moved to Paris. She took the portraiture skills she’d learned as a journeyman and began to explore the topic in earnest.

Traditional portraiture is about the subject of the photograph; sometimes it’s intended to be an accurate portrayal of the subject, sometimes a celebratory portrayal, sometimes a portrayal that’s revelatory. Vee Speers doesn’t take traditional portraits. It’s very clear that she’s intensely aware of the subject of the photograph, but her primary interest isn’t in portraying the subject at all; her interest is wider in scope. Speers uses portraiture of the individual as a method for exploring the nature of humanity in general.

Speers is probably best known for her series entitled Bordello. A decade and a half ago, she moved to Paris and found an apartment near Rue St. Denis. It’s a strange, dual-purpose commercial neighborhood. During the day it’s a center for the textile industry. At night, it’s a red-light district.

Inspired largely by the work of the noted photographer Brassai–and particularly his 1933 book Paris de Nuit–Speers began her Bordello series. The photographs feature actual prostitutes as models and were shot in existing bordellos. The images are more than a mere stylized homage to Brassai. They are, as she describes, intended to be “a kind of visual celebration of the mystery of seduction.”

It’s not seduction in the traditional sense, of course. Prostitution is a commercial enterprise and sex workers aren’t seduced; they perform a service for a fee. Speers is celebrating a different sort of seduction–the seduction of the night. It’s the seduction of the sort of life that’s lived in the urban half-light and in the dark when all the decent people are safe in their homes. It’s the seduction of the mask, both in a literal and figurative sense. Some of the figures wear physical masks to disguise their identity, but just about everybody in her photographs wears a figurative mask to disguise…something. Perhaps they want to mask their sexual needs, perhaps they want to mask their curiosity, perhaps they want to mask their intentions or their interests or their desires.

The dark helps mask everything, of course, and there is a darkness to the Bordello series. It’s not always a physical darkness, though that’s often present–figures frequently seem to emerge from a voluptuous, dark background in such a way that they appear to be an extension of the darkness. But the essential darkness of the series grows out of the aura of elegant decadence.

To emphasize the sensuous nature of the Bordello series, Speers printed the photographs using a 19th century hand-rendered charcoal-based process. It’s almost as if she felt the need to put her hands on the print–as if the print itself needed to be touched–before it was ready to be displayed to the public.

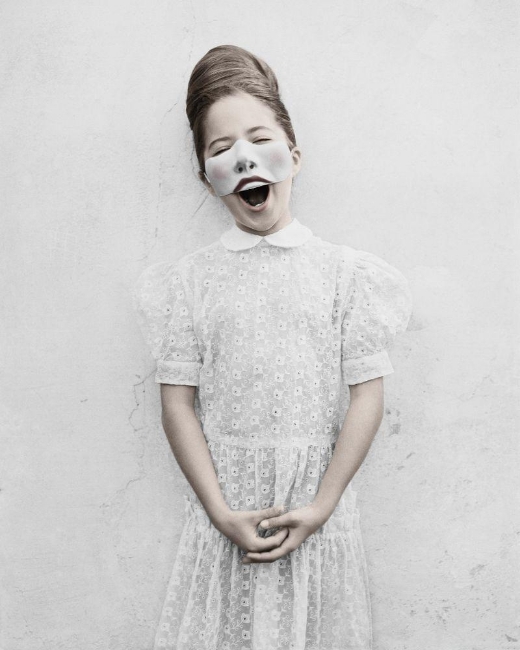

On the surface, Speers’ most recent series is about as far from the Bordello as possible. It’s the distance from prostitutes in decadent Parisian brothels to a child’s birthday party. Not surprisingly, that’s the title of the new series: The Birthday Party. Speers had taken portraits of children in a variety of costumes. The images themselves are fairly straightforward and simple. The seductive lighting of Bordello has been replaced by fairly common and uncomplicated studio lighting. The sultry angles and sideways poses of the prostitutes have given way to the simple front view / side view aesthetic of police booking photography.

But, of course, Speers’ work isn’t simple. She uses the surface normality and simplicity as another form of mask, another form of disguise. These are not portraits of children; they’re portraits of aspects of childhood that are generally unacknowledged. The subjects appear in costume, but these aren’t your standard cowboys or fairy princesses. These are children with secrets, kids with things to hide, pubescent phantoms of the opera.

“My photographs are linked to the human condition, the complexity of who we really are beneath the surface.”

Once again Speers is exploring hidden realities. Although children are usually depicted as innocent and simple beings, behind their bland exteriors they remain amazingly complex creatures. Speers understands that one aspect of childhood is an unacknowledged sort innocent savagery. She reveals some of that interior complexity while not revealing the children as individuals.

Speers deliberately, but subtly, emphasizes the freakish nature of the portraits by using carefully desaturated colors. That pallid quality suggests something almost unhealthy, as if hiding/masking the feelings and desires depicted in the photographs has rendered them morbid in the medical sense. The photographs, and the children in them, exude the feeling of having long been locked away in some quiet place without fresh air. There is a smell of mothballs and unguents about them.

“In my images there is a definite hesitation between genuine emotion and something more staged, a shift between real and surreal. But where does the reality begin, and where does it end? Wearing masks, playing a role or real life – is this strange, theatrical world any stranger than the universe we call our own?”

It may be more strange on the surface. But that’s problem with surfaces, isn’t it. It’s so difficult to know what lies beneath.