Imagine taking a fairly common idea and doing it so well that nobody ever expects–or allows–you to have another. Everybody who has both a camera and a dog has eventually turned the former on the latter. How could they not? Dogs are inherently photographable. But when conceptual artist William Wegman first turned his camera on his dog (a Weimaraner appropriately named Man Ray), something special happened. Something totally unexpected.

Wegman had built a name for himself as a conceptual artist before he ever owned a dog–in fact, before he turned to still photography. He was trained as a painter like so many well-known fine arts photographers; he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting from Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a Master of Fine Arts degree in painting from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. But he was originally best known for producing clever, amusing short videos that addressed more profound intellectual issues. These were seriously short videos–often less than two minutes–that approached a topic from a slightly off-kilter direction. There was a playfulness to the work that took the edge off the underlying satire.

That same playfulness led him to appreciate still photography in the late 1960s. During a telephone call, Wegman had idly sketched some small circles on his hand. As he spoke, he was struck by the similarity between those circles and the design of a ring he wore. Later that day at a party he reached for a slice of cotto salami and noticed that the circles on his hand and the circles on his ring were echoed by the peppercorns in the round slices of salami. It was a conceptual image that could best be expressed in still photography. He later made that photograph. “I never took a photograph like that, that was so graphically strong,” he said. “It cleared my mind.”

That photograph changed everything for Wegman. Where earlier his work had been intellectually and conceptually complex (as well as amusing), he began to pare down the elements to achieve a form of simplicity. He became a minimalist conceptual artist. In 1970 Wegman moved to Los Angeles. And he bought a dog.

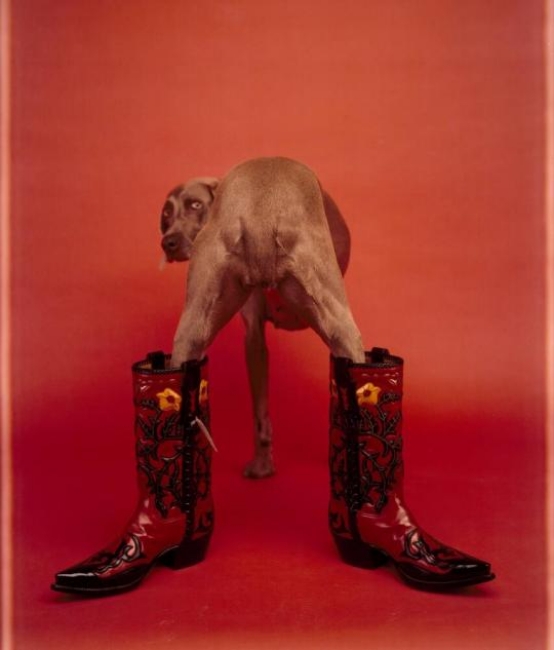

It was the best US$35 Wegman ever spent. In an interview, Wegman said he considered naming the dog Bauhaus but didn’t “because he wasn’t black and white and square.” Instead, he named the dog after an early conceptualist photographer, Man Ray. Over the next twelve years each made the other famous. In the same way the slice of cotto salami brought a new approach to Wegman’s conceptual photography, Man Ray brought a new element to his work. The dog allowed him to introduce affection and sweetness into his absurdist perspective. He used Man Ray in both his still photography and his short videos (such as Spelling Lesson, in which Wegman patiently explains to Man Ray the errors he made on his spelling test).

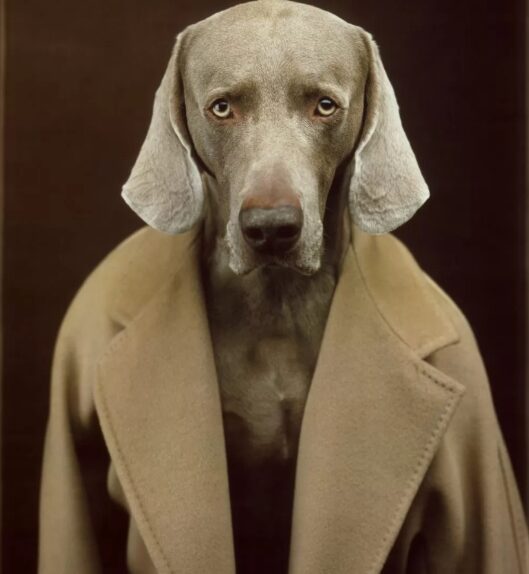

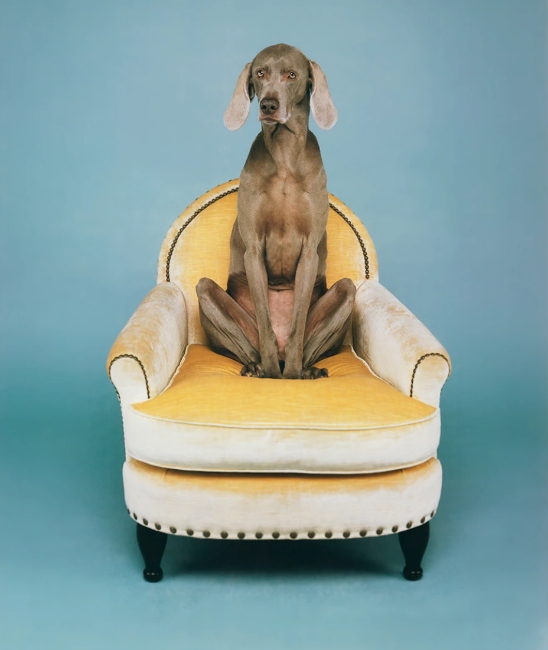

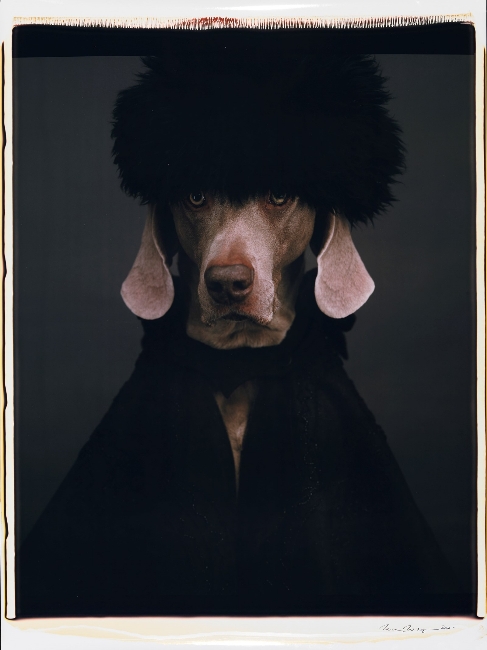

From the beginning Wegman discovered that Man Ray was a perfect photographic subject. Regardless of how Wegman situated or posed the dog, Man Ray retained an expression of calm intelligence and gentle dignity. It is that contradiction that creates the absurdity. One senses–and I’m convinced this is only partly a product of anthropomorphism–that the dog is complicit in the creation of the photograph.

Wegman said this of Man Ray:

“In a way, he is like an object. You can look at him and say ‘How am I going to use you?’ whereas you can’t with a person….You can manipulate him [although] he doesn’t feel manipulated, so he feels he’s doing something he’s supposed to do or having fun, one of the two.”

The photographs and short videos featuring Man Ray quickly became popular. Wildly popular. His still photography began to sell. His videos became featured on Saturday Night Live. He and the dog appeared on the David Letterman show. Man Ray was featured on calendars, post-cards, t-shirts. His other non-dog work got little attention. Both the art world and the world of popular culture wanted only to see the dog work. Wegman stated he began to feel like he’d been “nailed to the dog cross.”

“In the beginning, I didn’t even differentiate between working with the dog and not working with the dog,” Wegman said. He was only thinking about producing intelligent but accessible conceptual work. He and the dog developed a unique working relationship.

“I didn’t talk, I just listened to what he was listening to, the whole aura of smells and sounds and sights and things that he was picking up on during that day. Most people who have dogs see them as their dogs: ‘Come on, boy,’ or ‘Fetch’ or pat-pat. But they’re really teeming with their own thoughts.”

It was a productive and lucrative relationship. But over time, the demand for dog images became a burden. In the late 1970s Wegman decided to take a break from photographing Man Ray.

“I became sort of a strange, sad, lonely, hibernating sort of person who was antisocial and just wanted to make my own drawings and little crazy pictures. And everyone excused me for that because, of course, I was an artist and I was supposed to be crazy and reclusive.”

“We were both pretty unhappy,” Wegman later said about that period. “Man Ray would slump down in my studio, knowing there would be no games for him.”

In 1978 three things jolted Wegman out of that funk. First, a fire broke out in his loft and he lost much of the work he’d accumulated over the preceding eight years. Second, Polaroid offered to let Wegman use one of their new massive 20×24 view cameras. Wegman had always been intrigued by new technologies, and the notion of an instant camera that stood five feet high, weighed 235 pounds and produced images two feet across was immediately appealing. Third, Man Ray was diagnosed with prostate cancer and slipped into a coma.

Wegman’s veterinarian recommended putting Man Ray down. Wegman insisted on treatment and, to everyone’s surprise, Man Ray survived. The two began to work together again, producing stunning photographs. Over the next four years they created work that was so brilliant and clever and lovely that the Village Voice named Man Ray “Man of the Year” in 1982.

Man Ray died that same year.

There are two common reactions when a beloved dog dies. One is the desire to get another dog as soon as possible. The other is to never want another dog again. Wegman fell into the latter category. He turned back to painting. “The whole idea of the door became meaningless,” he said. “It didn’t matter if I went out or came in.” However, in 1985 he came across a litter of Weimaraner puppies and fell in love with a cinnamon-colored pup. He brought her home, named her Fay Ray, and claimed he wouldn’t photograph her. Not surprisingly, he wasn’t able to follow through on that claim. Wegman began a new partnership with Fay.

Fay Ray and Man Ray were very different dogs, however, and it took some time for Wegman to realize that. Man Ray was, for all his dignity, something of a ‘guy’ dog and enjoyed a certain amount of roughhousing. Not so with Fay. “I would try to play tug of war with her the way I’d done with Man Ray, and she’d just look at me like ‘Why are you shoving me?‘” Where Man Ray had been dignified, stately and solemn, Fay had a quality Wegman described as chameleon-like.

But their working process was much the same. “I always make sure I spend some time just seeing what they’re really doing,” Wegman says. Most people–including most dog owners–tend to unconsciously impose their worldview on that of the dog. Wegman talks about spending time, occasionally all day, just paying attention to the dogs.

Fay Ray eventually had puppies, and now Wegman’s world–and that of his family–is radically canine-centric. They have remodeled their New York City home with dogs in mind. He keeps a staff of assistants to exercise the dogs when he can’t. Wegman refuses to treat them like stars, however. Nor does he treat them like pets. Wegman’s dogs are simply fellow beings with whom he and his family share a space. When one of his children was asked at school if his family had any pets, he answered no.

Wegman came down off the ‘dog cross’ when Man Ray became ill. He’s never again felt burdened by his connections with the dogs. He has found a strange sort of rapport with his dogs, even though when they’re in front of the camera he photographs them like objects. You can look at a dog, he says, in ways you can’t look at people. “If there were two women on the couch and I started staring at them, one of us would start to feel uncomfortable,” he has said. But the dogs don’t mind.

Wegman’s story isn’t just a story of a conceptual artist, although he certainly fits into that category. It’s not a story about photography or art at all. In fact, it’s not even Wegman’s story. It’s mostly the story of Man Ray, Fay Ray, and her pups.

To be perfectly honest, I don’t think this is a dog story at all. In the end, it’s a love story.