Alexey Titarenko was born in 1962 in the coastal city of Leningrad in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Photography occupied a strange position in the Soviet Union. Marxist theory holds that capitalist societies are arranged so that the world of art and art appreciation largely excludes the working classes. The socialist State, therefore, deliberately made basic art materials and instruction easy to obtain, especially for students. Granted, the equipment was unsophisticated and often out-dated, but it was virtually free. Becoming a photographer in the Soviet Union was relatively simple. The practice of photography, on the other hand, was significantly less so.

In the Soviet Union, photography–especially professional photography–was expected to serve the State and glorify the socialist ideal. That meant Soviet photography turned out a lot of well-crafted photographs of sturdy-looking men on tractors and images of cheerful factory workers. In addition, galleries and museums were controlled by the State, which restricted the sorts of images that could be shown.

Artists did, of course, create work that wasn’t–and wouldn’t/couldn’t be–approved by the State, but such work was generally a subterranean activity. Literature, dance, poetry, painting, music, or photography that didn’t fit the socialist model was created underground and only acknowledged by other underground artists.

This was the system under which Alexey Titarenko spent the first three decades of his life. This was the system that shaped his approach to photography. In 1991 when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was officially dissolved, that system disappeared. Thirty years of suppressed artistic impulses, however, aren’t so easily shaken off.

Titarenko’s world view–and his view of photography–is not only a product of the old Soviet Union, it’s also a product of his hometown. The town was originally named St. Petersburg. It was built on the site of a Swedish fort captured by Tsar Peter the Great in 1701 during the early days of the Great Northern War. The Tsar named the town not after himself, but after his patron saint. Although the initial construction of the town was done by conscripted serfs, Peter relied on designs by Dutch and German engineers. He also invited merchants, scientists, artisans, shipbuilders and scholars from all over Europe to populate his new city.

That influx of intellectuals and skilled immigrants made St. Petersburg the most cosmopolitan city in Russia and it quickly became the cultural and intellectual center of the nation. The Dutch and German influence was so pronounced that at the beginning of the First World War in 1914 the name St. Petersburg was thought to be “too German.” The city’s name was officially changed to the more Russian-sounding Petrograd. That name was short-lived, however. The Russian Revolution took place in 1917 and the Soviet Union was born. A few days after Lenin died in 1924, the city was again renamed: Leningrad.

Much of the city was destroyed during World War II when the German Army laid siege to it. The Siege of Leningrad was one of the longest sieges in modern history, lasting from September of 1941 to January of 1944. A million and a half people died during the siege; the physical damage was so massive that even today there are empty lots in the suburbs where buildings stood before the war.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the city resumed its original name. The history of this particular city is important to this salon because Titarenko loves and photographs his city with the same passion that Brassaï gave to Paris. Growing up in the most European of Soviet cities, being given ready access to basic photographic equipment, being forced to hide his more creative impulses, then seeing his city change radically after the demise of the Soviet Union–those realities have shaped Titarenko’s photography.

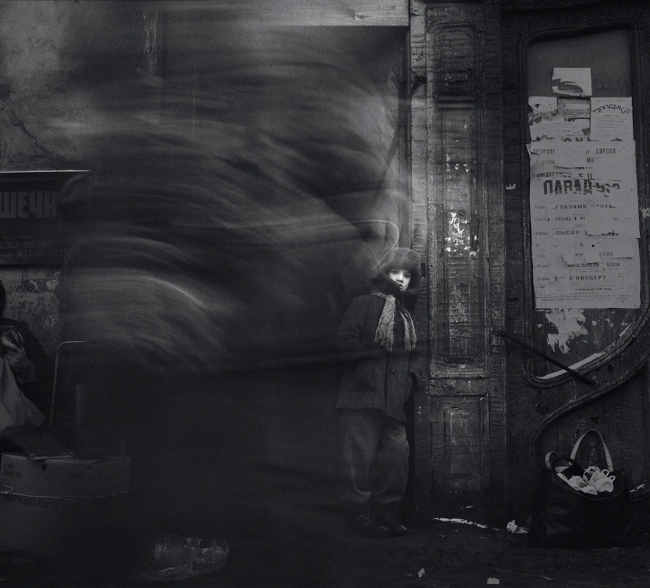

The photographs in this salon were all taken in the first few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Titarenko, using an old medium format camera and very slow black-and-white film, made moody, loving but honest, long exposure photographs of his city and its people. The mood is partly an artifact of the primitive Soviet-era equipment, but it also comes from Titarenko’s work in the darkroom. He uses the old techniques, selective bleaching and toning, dodging and burning, to create an almost eldritch combination of airiness and somberness.

For the most part, the people in the images are presented as phantoms…mere blurs that only occasionally present themselves as recognizable individuals. The photographs suggest that the people are indistinguishable and temporary, whereas the city itself abides.

In a way, these are very socialist images. The phantasmagorical people moving ghostly through the streets reinforce the concept of community while diminishing the significance of the individual. In addition, the images depict the momentum of social change that came after communism; some individuals thrived, others were allowed to fall by the wayside. In the USSR old women often needed to stand in long lines to obtain basic staples–bread, meat, flour. Under the new economic system, the quality of goods improved and increased in variety. The old women, instead of standing in lines, sometimes found themselves sitting on the curbs begging for the money to buy the necessities once provided at low cost by the State.

Titarenko doesn’t judge the changes. He doesn’t really attempt to document the changes. He simply sets up his camera and opens the shutter. This is his city, these are his people, this is the reality of the city and the people.

When asked about his influences, Titarenko names an earlier resident of St. Petersburg, the Soviet-era composer Dmitri Shostakovich. One doesn’t ordinarily consider classical composers as being particularly influential on modern visual artists, but Shostakovich occupies a unique position for Titarenko. Shostakovich and his works were officially denounced twice by the Soviet government, his compositions were periodically banned. He avoided joining the Communist Party until 1960, when he was 55 years old. Shostakovich wasn’t a rebel, at least not in the sense that he was turning his talents in opposition to the government. He was simply a musician who believed the State had no legitimate authority over music. It’s a position with which Titarenko concurs.

Titarenko was particularly influenced by Shostakovich’s Second Cello Concerto. He has called the concerto “music that is the conscience of a destroyed culture, and a very precious reminder of the frailty of humanity.”

“During my walks around the city, I realized that St. Petersburg offered endless living illustrations of this [concerto]. The monotonous opening cello melody was one of despair, but also of expectation. The concerto was instrumental in realizing certain images.”

Certainly, there is lyricism in Titarenko’s work. Some of that is a product of the long exposures and Titarenko’s darkroom technique, but it also grows out of the total lack of irony in the work. There is no sense of being cleverer-than-thou or being tongue-in-cheek. Titarenko is honestly and deeply in love with his city and honestly and deeply concerned about what happens in and to it.

Looking at the photograph above (which I confess is my favorite Titarenko photograph), I’m reminded of Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment. That dark blot of a figure could be Raskolnikov skulking through the streets of St. Petersburg, plotting the murder of the pawnbroker. It is a figure that seems to exist outside of normal time, a figure that is equally real and fictional.

All of Titarenko’s images of St. Petersburg seem to belong as much in the past as they do in the present. They could, in fact, be said to be ruminations on the very notion of time. The photographic and printing techniques used by Titarenko are the same used by 19th century photographers. His approach is decidedly low-tech and very labor-intensive. Each photograph takes a few days to complete by hand–and could likely be done in as many hours using modern technology.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union Alexey Titarenko has done well for himself. His work is now exhibited throughout Europe and the United States. He could easily afford modern equipment, he could easily choose to use modern techniques. His choice to rely on old gear is an odd act of socialist solidarity. The object of that solidarity isn’t socialism, however; the object is his city.

His city is worth the extra work. His city has earned it.