Milton Rogovin never intended to be a photographer, let alone one of the most renowned social documentary photographers in the U.S. He was an immigrant’s son who felt privileged to go to college and lucky to obtain a degree that would allow him to enter the professional classes rather than the merchant or worker classes. His photography career, oddly enough, was a response to political repression.

He was born in New York City in 1909, five years after his parents immigrated from Lithuania. His family opened a small dry-goods store in what would eventually become Spanish Harlem. They were successful enough that Rogovin was able to attend Columbia University, from which he graduated with a B.S. in Optometry. Unfortunately for Rogovin, his graduation coincided with the collapse of the stock market in 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression.

Not long after his graduation, his family lost their store. Then they lost their home. Soon thereafter, his father died of a heart attack. Rogovin was able to find work in Manhattan as an optometrist, but the Depression and the toll it took on is family opened his eyes to the realities–and the politics–of poverty. He joined the United Optical Workers Union and began to read the Daily Worker, the communist newspaper published in New York. He also became active in various workers’ causes. These were the first steps on a long road that led him to both ruin and success.

Although the U.S. economy gradually improved, it collapsed again in 1937. Rogovin was forced to relocate to Buffalo, New York the following year. There he opened his own optometry office in a working class neighborhood and started a practice that primarily served union members. With war looming in Europe and an active civil war raging in Spain, Rogovin expanded his political activities. He joined the American League Against War and Fascism and helped raise money to support the Republican cause (the U.S. government, though officially neutral, sold aircraft to the Republican forces and gasoline to the Nationalists).

The U.S. entered the Second World War in 1941. The next year brought significant changes to Rogovin’s life: he married, he volunteered (at age 33) to join the Army, and he bought a camera. His military career was unexceptional; not surprisingly, he served much of it in a hospital in Cirencester, England as an optometrist. At the end of the war in 1945, Rogovin returned to Buffalo, his wife, and his optometry practice. He also resumed his political and union activities. In response to the post-war treatment of African-American veterans, he began to assist with voter registration in the black community of Buffalo. The Rogovins also protested the arrest, prosecution, conviction and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for spying for the Soviet Union. As the Cold War intensified, all those activities brought Rogovin and his wife to the attention of the FBI.

In 1957 Rogovin was subpoenaed by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which was investigating alleged communist influence and infiltration. He refused to answer their questions, citing his rights under the Fifth Amendment. That same year, his wife refused to sign the ‘loyalty oath’ required by the Buffalo public school district. The Buffalo news media began to refer to Rogovin as “Buffalo’s Number One Red.” Not surprisingly, his optometry clients drifted away.

At age 48 Milton Rogovin found his ability to earn a living was badly compromised, his political activities were severely curtailed, and his life was dramatically changed. A friend who taught music at the local state university was involved in a project recording the services at a local African-American church. He invited Rogovin, who found himself with a lot of free time, to accompany him. Rogovin agreed. He brought along his camera.

It was a fateful decision. Rogovin continued to return to the church–and other churches in that community–to photograph the services.

“When the McCarthy committee got after me, my practice kind of fell pretty low. My voice was essentially silenced. I thought I would be able to speak out about the problems of people, this time through my photography.”

And speak he did. Rogovin’s photographic series on the storefront churches of Buffalo garnered some attention–not just among progressive political groups, but also from some prominent photographers. Minor White found the photos moving and eventually helped get them published in book form (with an introduction by W.E.B. DuBois).

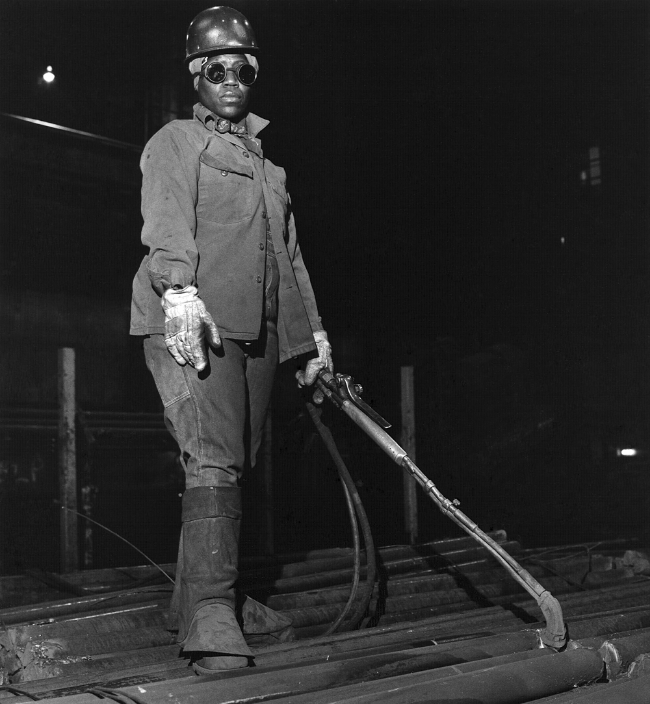

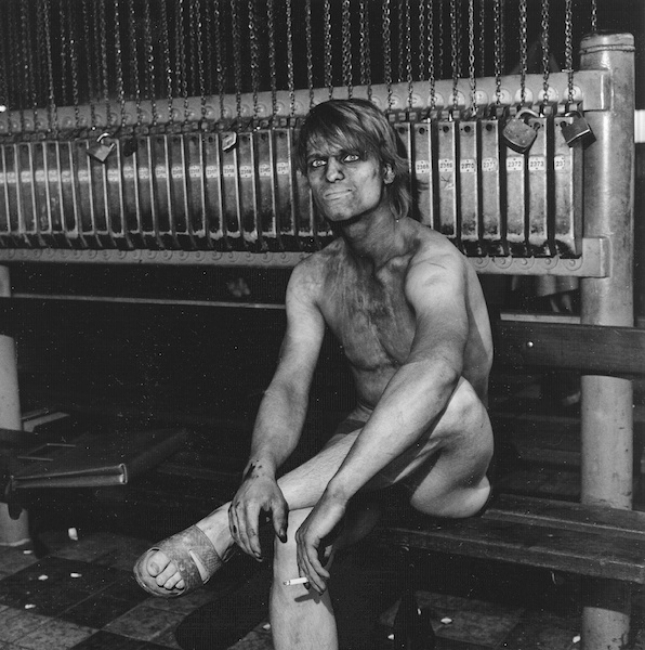

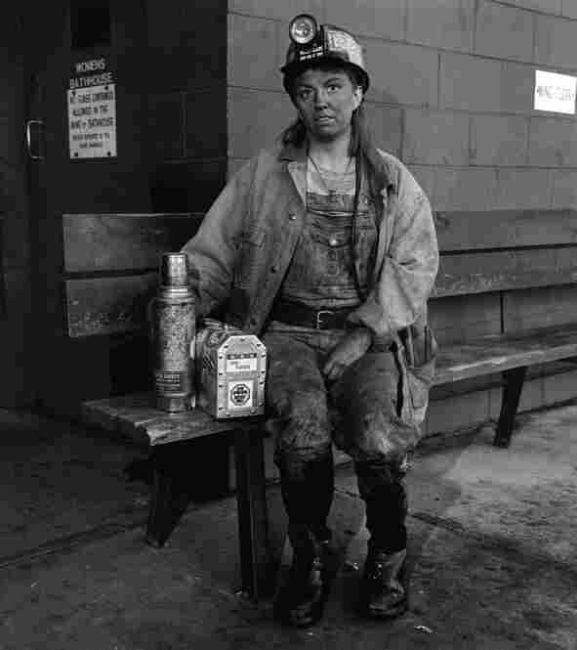

Encouraged by the reception of the photographs, Rogovin turned his camera on other disadvantaged, marginalized or economically oppressed groups (and, as always, union members). Native Americans living on reservations in the Buffalo area, mill workers, miners, foundry workers. Rogovin seemed to feel an especial affinity for miners; he and his wife spent a few summers living in their car while he photographed coal miners in Appalachia. The success of his Appalachian photographs sparked an epic attempt to document mine workers throughout the world. Over the years he was invited to France to photograph coal miners there, and to Scotland and Spain, and to photograph the nickel miners in Cuba, and to Germany and Zimbabwe and China. In between these many trips, which were often supported by local unions, Rogovin continued to photograph the people living in the poor and working class neighborhoods of Buffalo.

As a self-taught photographer, Rogovin’s technique was simple and unsophisticated. He relied on the Rolleiflex twin-lens reflex camera he bought the year he was married. When photographing inside, he used the simple bare-bulb flash method Minor White had explained to him. He simply approached the people he wanted to photograph, asked their permission, then took the photographs.

By returning to the same neighborhoods, the same churches, the same union halls, the same factories, the same local taverns week after week, month after month, year after year, he earned the trust and respect of the people. The people he photographed at work, he would generally ask if he could later photograph them at their homes. He was, it seems, rarely refused. After photographing his subjects, whether at home or at work or at church or in a bar, the next time he returned to that location he would bring small prints to give to his subjects.

The continuity of those small relationships allowed Rogovin to document changes over time–changes both to the individuals and to the community. Rogovin began to print triptychs and quartets showing those changes. They show the pride and satisfaction of people who had done well and improved their lot in life, and they show the corrosive results of the collapse of the steel industry and the lost jobs and lost homes and the decline into poverty. They show the lives of the common people of Buffalo.

“All of these people have tremendous possibilities, and it’s going to hell. That’s why I want people to look at this damn stuff.”

As he grew older, Rogovin’s eyesight was marred by severe cataracts. It became increasingly difficult to photograph “this damn stuff.” In 1997, forty years after taking those first documentary photographs in one of Buffalo’s storefront churches, he gave up photography and sold his camera.

In those intervening years, though, Rogovin had gone from being “Buffalo’s Number One Red” to a well-respected social documentary photographer. His work had been published in more than 150 journals and magazines, he’d published eight books of photography, he’d had his photographs exhibited in more than 30 group shows and over 60 solo exhibitions. A documentary film had been made about him. He’d taught courses in social documentary photography at the local university. Two years after he sold his camera, the Library of Congress acquired more than a thousand of Rogovin’s master prints. The same government that had tried to silence his voice in the 1950s now honored the work he’d done.

“The rich have their own photographers. I photograph the forgotten ones.”

In 2000, his vision was restored through new techniques of cataract surgery. Later that year, he bought back the Rolleiflex camera he’d sold and returned to photographing the forgotten ones.

Earlier this year, 2007, Rogovin was given the Cornell Capa Award by the International Center of Photography. This month, December, Milton Rogovin turned 98 years old.