Some photographers want to document reality. Some want to create images that exist only in their minds. Chris Anthony, it seems, wants to invent new realities. He wants to craft internally consistent environments and populate them with characters who seem perfectly adapted to those environments. The realities Anthony creates may not be altogether welcoming or entirely pleasant, but they have a strange and compelling power.

Chris Anthony first picked up a camera when he was a teen-ager in Stockholm, Sweden. Like so many teens, he took photographs at concerts. He created a fanzine that drew some attention and soon found himself shooting concerts semi-professionally. Despite that early success, Anthony abandoned still photography when he moved to Italy to study art history. Art history, in turn, gave way to cinematography. For the next decade or so, Anthony worked almost exclusively in cinema. He directed music videos and commercials, he made short narrative films, he even dabbled in cartoons.

Anthony also moved frequently–Sweden, Italy, Andalusia, Morocco. Around the turn of the century, he moved to Los Angeles. Perversely, once in the land of Hollywood, he abandoned film and returned to still photography. He found he preferred the independence of still photography. He didn’t need a crew, he didn’t need a lighting team or camera operators, he didn’t need a sound team. All he needed was a camera and somebody to photograph. And his imagination.

Just as he did with cinema, Anthony continued to combine commercial work and his own interests. He shot the photographs for the CD jacket and posters of My Chemical Romance’s The Black Parade. He did the same for Modest Mouse. He created images for Sony Playstation advertisements. “The commercial side is really interesting and fun as well,” Anthony told an interviewer. “I’ve been extremely lucky to do a few things that were really quite up my alley. It didn’t feel like I was in any way whoring myself out or anything.”

Indeed, his work with My Chemical Romance (as seen in the portrait below) is almost indistinguishable from his personal work. Although he enjoys the commercial work, he admits he does it because it allows him to do the fine arts photography he really wants to do. With the fine arts photography, he has the opportunity to truly express himself. His more recent work is topical, yet it’s very clearly grounded in a well-considered personal aesthetic.

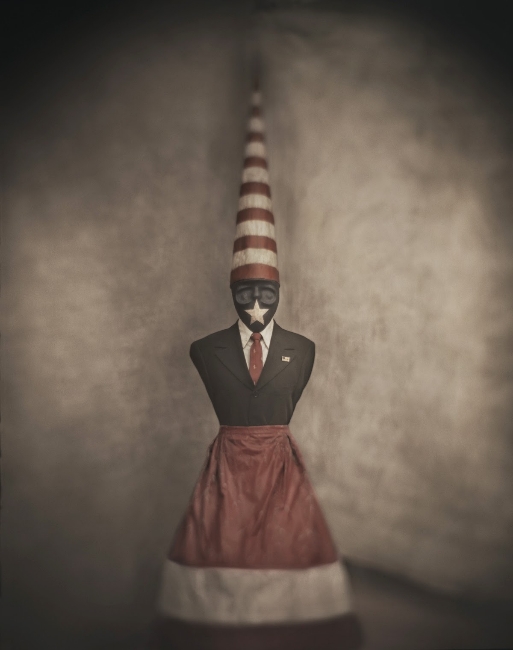

Anthony’s recent work tends to be set in a dystopian sort of alternate Victorian universe. It’s reminiscent of the steampunk aesthetic, but without the steam. It’s a dark, ornate world. A haunted world in which beauty is almost always tinged with some sort of corruption, a world in which every hint of innocence also carries a corresponding suggestion of depravity.

Anthony goes to great lengths to achieve the effect he wants. He uses a number of different cameras, though his primary tool is a modern large format camera fitted with antique lenses (he has amassed a collection of lenses that span from 1870 to 1910). These lenses have no iris and aren’t synchronized with a shutter. Anthony shoots in the old style–by removing the lens cap for a period of time, then replacing it. The result is a strange combination of sharpness and subtle blurring.

Anthony’s attention to detail includes the use of traditional Victorian lighting. The portrait studios of that pre-flash era generally included a skylight in the ceiling, beneath which the subject would stand or sit. He recreates that soft light coming from above either by using the same skylight technique or by more modern means, such as an Octabank softbox set on a boom as high as possible above the subject. He also sometimes enhances that effect in post-processing.

He does considerable post processing. In addition to the large format camera, Anthony frequently uses medium format cameras (he uses both a Hasselblad and a Mamiya) to shoot details or objects which will later be digitally inserted into the final image. He often mutes colors, manipulates the saturation levels of specific parts of the image, and creates textures that will enhance the gruesome fairytale ambience he’s after.

That combination of old and new technologies, the mixture of Victorian and modern sensibilities, and the amalgamation of antique appearance with current aesthetic cues gives Anthony’s work an out-of-time quality. It has earned him a Lucie Award nomination and the honor of receiving the Grand Prize for American Photo’s Images of the Year in 2007.

His work, not surprisingly, is influenced by his experiences. His interest in light and Victorian design and composition are a result of having studied art history as well as by having lived in various architecturally and historically rich cities. His tendency toward implied narratives is an outgrowth of his time as a director, as is his love of wide formats. These are seriously wide; his recent Victims & Avengers series is displayed as 4×7 foot prints.

It would be easy to suggest that at least part of the macabre and morbid aura that infuses Anthony’s work is a result of his childhood experience as a witness to domestic abuse. His series Victims & Avengers deals specifically with that issue, depicting scenes in which women and children have apparently struck back against their abusers. Anthony himself makes that connection.

“I saw [domestic abuse] and heard it as a little kid. It’s been with me all my life. The uncomfortable and horrific situations that you’re in as a victim or a witness….I suppose it’s cathartic, or perhaps it’s some form of therapy, but it was something I felt strongly about. I chose to put it in this entirely different world, and in doing so, distance myself from it.”

It could be said that in many of his more personal photographs, Anthony is trying to put the bogeyman back under the bed where he can’t do any harm, or turn him out of the house altogether.

Chris Anthony is not yet forty years old. Despite his teen experiences with a camera, he’s only been seriously making still photographs for less than a decade. Yet we can clearly see how his work is evolving. It is becoming more personal, more idiosyncratic, more clearly his own. It may sometimes evoke a steampunk sensibility, but it’s a natural consequence of his life experiences and interests. He’s not simply following a trend; he’s following his instincts.

“At the end of the day,” Anthony says, “if I could draw worth a damn, I’d probably be a painter, not a photographer.” We are, I think, fortunate he never learned to draw worth a damn.