He was born in a parsonage in Cheshire in 1832 to a very conventional Anglican family. Like his father, after whom he was named, Charles Dodgson would eventually take holy orders in the Anglican Church. It was just one of many career paths Dodgson would follow in the odd course of his life.

A proper Victorian boy, Dodgson attended his father’s college of Christ Church in Oxford where, again like his father, he studied mathematics. He showed a natural talent for maths and on graduation was awarded with the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship–a post he would hold for the next quarter of a century. He wrote a number of scholarly treatises on aspects of math, including An Elementary Treatise on Determinants with their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Geometry and The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically, so far as it Relates to Commensurable Magnitudes. Dodgson was equally interested in writing fiction, for which he would later become quite famous.

Given his interests in math and science it’s not surprising that Dodgson, while still a student, took up the camera. At that point in time, photography was just beginning to be accessible to the dedicated amateur. The newly invented “wet collodion” process made the enterprise significantly less demanding than the earlier daguerreotype process. Even so, photography could not be considered easy. It required the photographer to precisely mix chemicals in the dark and apply them evenly over a sheet of glass to create the ‘negative.’ The negative had to be placed in the camera while the chemicals were still damp (hence the designation ‘wet’) because the lost their photosensitivity when dry.

Like so many amateur photographers, Dodgson made his first photographs with a camera borrowed from a friend. He was so taken by the practice, though, that he traveled to London and purchased his own camera for £15 (a considerable sum in those days). Because the exposure times were so long (exposures of 10 to 45 seconds were common) he began by shooting primarily landscapes and medical specimens. However, he quickly moved into portraiture.

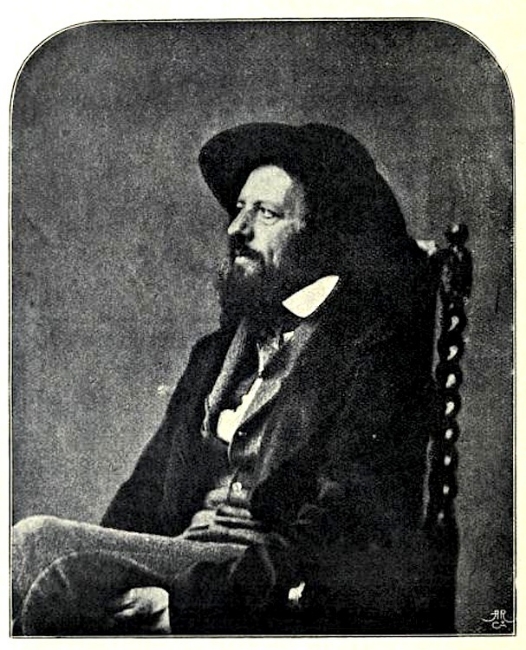

He became so skilled that he was soon photographing well-known Victorian celebrities. Alfred, Lord Tennyson sat for him, as did Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the scientist Michael Faraday and Prince Leopold (the fourth son of Queen Victoria). There has been some speculation that Dodgson engaged in portraiture in large part because it gave him access to a better social class than he would otherwise merit in Victorian society.

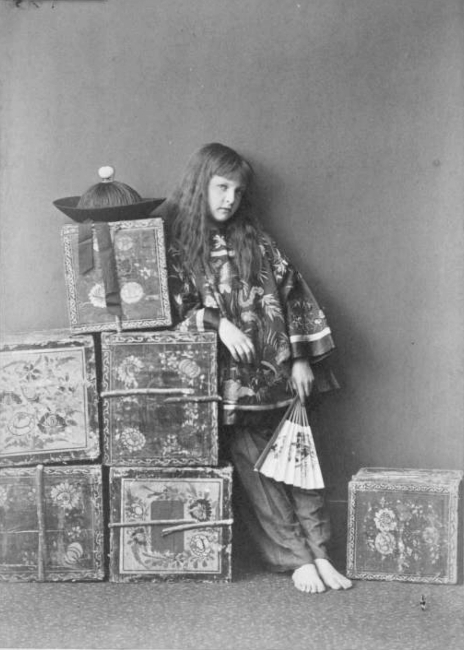

In 1856, the same year Dodgson took up the camera, the college of Christ Church obtained a new Dean, Henry Liddell. Dodgson became quite friendly with Liddell and his family, including the Dean’s three daughters (Alice, Lorina, and Edith). Dodgson often photographed the Liddell children, frequently having them dress in costume and acting out scenes from literature. He also entertained the children with stories, one of which he put to paper and later decided to submit for publication. Given that he held a responsible position at the university and published serious works of mathematics under his own name, Dodgson chose to have the story published under a pseudonym: Lewis Carroll. The story was called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Very few photographers of that era photographed children. This was partly because children weren’t considered important enough to photograph and partly because the long exposure times required children to hold perfectly still for at least half a minute–never easy to do, even for adults. Dodgson, however, showed a rare capacity for getting children to cooperate. Over half of the one thousand existing photographs known to have been taken by Dodgson were of children. Six of those photographs show children in the nude.

Much has been made of Dodgson’s child photography and his friendliness with children. There have been numerous suggestions that Dodgson was a pedophile. The primary evidence to support the accusation, which only surfaced several years after his death, appears to be the existence of the photographs themselves. It should be known, however, that it wasn’t uncommon for those few Victorian photographers who worked with children to photograph them in the nude. Both Oscar Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameraon photographed children in the nude. In fact, nude children were even featured in Victorian Christmas cards. In each case when Dodgson photographed children in the nude he did so with the permission of the parents, who received copies of the prints. According to a study of Dodgson’s journals published by Princeton, over the course of 13 years he shot a total of 30 nude photographs in eight sessions involving the children of six families.

The fact that Dodgson never married has also been advanced to support the accusation of pedophilia. There is ample evidence, though, that he was friendly–and perhaps romantically involved, it’s unclear–with a number of adult women. Some suggest one reason Dodgson remained unmarried was because he suffered from epilepsy. Epilepsy was just beginning to be understood as a medical condition during the Victorian era. Nevertheless, a certain stigma remained attached to it; it wasn’t uncommon for epileptics to be confined to mental institutions. His epilepsy also appears to be the reason Dodgson took holy orders as a Deacon rather than a Rector. He feared he might have a seizure during a sermon. In his diary, he wrote: “I really think sermons may have something to do with them [the seizures].”

Whether Dodgson’s personal life is evidence of pedophilia or merely an example of differences in culture and time, who can say.

Dodgson’s name is, of course, inextricably linked with that of Alice Liddell, who had the distinction of being the namesake of perhaps the most famous children’s book ever published. In an interview, she spoke of Dodgson’s skill at child portraiture. He would get the children to relax by telling them stories, then “when we were thoroughly happy and amused at his stories – he seemed to have an endless store of these fantastical tales – he used to pose us, and expose the plates before the right mood had passed. Being photographed was therefore a joy to us and not a penance as it is to most children.”

Alice may have inspired the Wonderland stories, but she was not his favorite photographic subject. That distinction belonged to Alexandra “Xie” Kitchin. He photographed her more than any other person–at least fifty times over eleven years. In fact, the last photograph Dodgson shot was of Xie (pronounced “Eksey”). The photographs he shot of Xie have been called “the most captivating [images he] ever produced.”

The thing that distinguishes Dodgson’s child photography from that of other Victorian photographers is the children, though necessarily posed, are rarely posed formally. He routinely showed them engaged in a child’s activities…playing make believe, taking part in sports (or resting afterwards), reading books, climbing trees. In addition, Dodgson made some radical departures from established photographic technique. Instead of having his subjects orient themselves to the position of his camera (which, of course, had to be situated on a tripod), he oriented his camera to the position of his subjects. If the children were on the ground, Dodgson would lower his camera as low as possible. He wanted the camera to be at child level. He also consulted his child subjects and had them suggest how they wanted to be photographed.

Despite his growing fame as Lewis Carroll–and the attendant increase in income–Dodgson remained at Christ Church until his death in 1898. He continued to write scholarly works in mathematics as well his more popular fiction. But in 1880 he gave up the camera.

Why? It appears he grew bored with the drudgery associated with it. In a letter written in December, 1881 to a Mrs. Hunt, Dodgson said:

“The last photograph I took was in August 1880! Not one have I done this year: as there was no subject tempting enough to make me face the labour of getting the studio into working order again… It is a very tiring amusement, and anything which can be equally well, or better, done in a professional studio for a few shillings I would always rather have so done than go through the labour myself.”

Charles Dodgson was an odd character, no mistake. Even in an age known for eccentric personalities, he stood out. A mathematician of some repute, an author of immensely popular childrens books, a sought-after portrait photographer, an Anglican clergyman. He had one of the most creative minds of his generation (who else, looking at an ancient, gnarled tree in the gardens of Christ Church college, could have conceived the poem Jabberwocky?). A century after his death, prints of his photographs are sold for huge amounts of money (a print of Alice as the Beggar Maid recently sold for approximate a quarter of a million dollars).

In the end, what one makes of Dodgson–epileptic genius, pedophile, or harmless eccentric–probably depends a lot on one’s own view of the world. I have my own opinion, of course. But mostly I’m just glad that photograph of young Alice Liddell exists. I’m glad the Alice stories exist. I’m glad the phrase “O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!” exists. It would be a duller world without them.