Matt Mahurin is hardly a household name, but you’re probably familiar with some of his work. You may not be aware of it, but you’ve almost certainly seen it. Mahurin created one of the most controversial images of the 1990s and sparked a debate that is still ongoing.

Born in L.A. in 1959, he seemed almost destined for a career in the visual arts. Like so many of the photographers we’ve discussed in these salons, Mahurin’s first love was painting. What he liked, it seems, was the actual process of painting. Deciding on the subject matter, laying it out, sketching, applying the paint. He liked the ritualistic pattern of making a painting.

There was no moment of epiphany that led him to shift his interest from the process of making a painting to the process of making a photographic print. There was no road-to-Damascus event. Mahurin just found himself gradually moving away from painting and toward photography.

He was still primarily in love with the process of creating the image. The difference was that when he painted, he was usually alone in his studio. When he began to shoot photographs, he found it necessary to go out into the world and interact more immediately with it.

“I was at the mercy of what was in front of the camera. I had to adapt to that. When I was painting, the limitations were the limitations of my own abilities, my own imagination.”

What the larger world outside his studio offered was this: raw material. Dynamic raw material. Raw material that acted and behaved according to its own rules and whims. Raw material that did unexpected and surprising things.

Mahurin developed a unique tenebrous style. Dark, heavily laden with deep shadow. Full of obscure shapes, a tad threatening, emotionally distressing. Perhaps the most common term used to describe Mahurin’s work is this: unsettling. Profoundly unsettling. Looking at his work–especially his earlier work–is like being a voyeur in another person’s nightmare.

At the same time he was creating these dark, disturbing photographs, Mahurin was also doing drawing and photo-illustrations for TIME magazine. He not only illustrated articles, he created images for the magazine’s cover. He did his first cover illustration when he was only 23 years old.

Just as he moved from painting to photography, Mahurin eventually moved from still photography into video. He was asked to bring his style to music videos. He was soon directing videos for Peter Gabriel, Metallica, U2. He was still primarily interested in the process of creating the image. He’d gone from being alone in his studio with his paints and brushes to being involved with a limited number of people and a camera out in the world. Now the process required multiple cameras and “cranes and crews and Winnebagos and rooms full of computers to transfer the film.”

The process became too big, too much. So he abandoned it. The film production company he’d created to make music videos—he closed it. The studio he rented in which he shot the videos—he got rid of it. And he started seeking ways to do the same work in simpler ways.

Advances in technology allowed him to do work without the massive crew, without all the elaborate post-production facilities, without all the attendant fuss. He began making inexpensive documentary films. Films like Mugshot and I Like Killing Flies earned positive critical reviews, though they weren’t necessarily commercially successful.

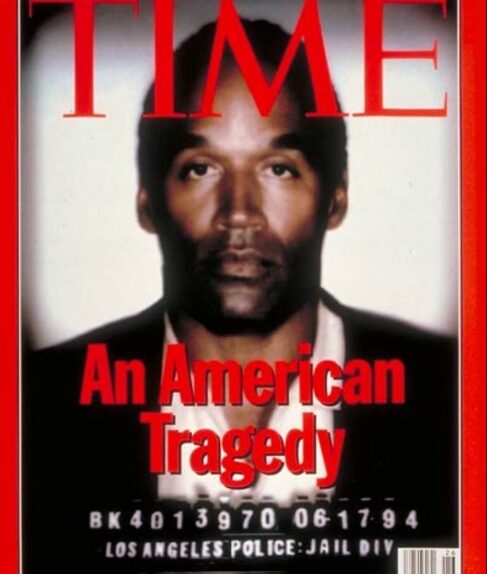

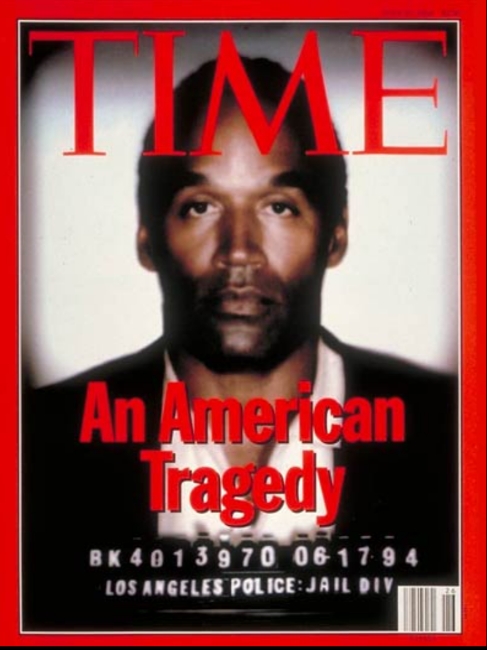

During all this Mahurin continued to do photo-illustrations for TIME magazine. In 1994, former football star O.J. Simpson was arrested for the murder of his wife and another man. TIME, like all the other news magazines, chose to make the murder and Simpson’s arrest the cover story. The editors of TIME commissioned a number of artists, photographers and illustrators to prepare potential cover images. At 2 a.m. Eastern time, the L.A. police released Simpson’s mugshot. With only a few hours before the printing deadline, the editors decided to give the mugshot to Mahurin.

Mahurin applied his signature dark, menacing style to the mugshot. The resulting cover image created a perfect storm of outrage and criticism. The magazine was vociferously condemned; Mahurin was tagged as a racist. It was a lesson for the 34-year-old illustrator.

“As an image-maker, I work in a dark palette. Whether it was my Time cover on domestic violence, nuclear terrorism—or a former football hero who is suspected of murder—much like a stage director would lower the lights on a somber scene, I used my long-established style to give the image a dramatic tone…. For me, the controversy was as much about power as it is about racism. Time magazine had the circulation power to reach millions of readers—and I had the power to make the image that they would see…. In the end, my career has been in pursuit of the power of the image and it is through this power of the image that we become educated and in the end, this is what we should hold on to; that we have been educated as to how images can he perceived.”

That cover image initiated a debate about how news venues utilize photographs. It’s a debate that continues today.

Mahurin continues to do still photography, to shoot documentary films, to work as a photo-illustrator. His latest photographic work retains the dark aura of his earlier work, but is significantly more simple. Any post-processing is done the old-fashioned way: in the darkroom.

“All the images are just straight, no digital anything. Prints from negatives, on paper.”

In interviews, Mahurin always seems to stress the process by which he creates his images. He’s apparently more reluctant to discuss the images themselves. This seems to be a deliberate policy to avoid explaining the work, to allow…or perhaps require…viewers to form their own impressions.

My impression is that Mahurin is the Cartier-Bresson of the Bad Dream. He seems to have a sort of genius for catching the fleeting, peripheral, paranoid moment. His images strike me as the sorts of things a soothsayer might notice before pronouncing some evil omen.

I like them very much.