He was born to an affluent family in Warsaw in 1911 and given the name Dawid Szymin. His father, Benjamin, was a publisher of books in Hebrew and Yiddish. The family fled Warsaw after the city was bombed at the beginning of the First World War. The next few years were spent in Minsk and Odessa. Although the Szymin family returned to Warsaw at the end of the war and re-established their publishing business, those formative years seem to have established a pattern. Szymin’s life would be bounded by conflict, by travel, by uncertainty, and by adapting quickly to every situation.

When he was 18, Szymin’s family sent him to Leipzig, Germany to study design and printing technology at the respected Staatliche Akademie für Graphische Künste und Buchgewerbe. It was hoped he’d eventually assume responsibility for the family publishing business. Social and political events were to make that impossible, however. After the world war, neither Germany nor Poland were particularly supportive of Jews; publishers of books in Hebrew and Yiddish weren’t particularly welcome. The business was on the verge of failure. In 1932 Szymin left his family again, this time for Paris.

His ostensible plan was to study chemistry and physics at the Sorbonne. Although his family had offered to give him a monthly income, Szymin was unwilling to cause them any unnecessary expense. Instead of going to school, he chose to find work. A family friend owned a small photo agency, Agence Rap which supplied images to magazines and newspapers; he loaned Szymin a 35mm Vidom camera and put him to work as a freelance photographer.

Szymin found himself in the right place at the right time. The 1930s was a revolutionary period in photojournalism. Photo-centric mass-appeal magazines were multiplying throughout Europe and the Americas. The magazine Regards, which focused on left-wing politics, sports, and popular entertainment, hired him as a full-time photojournalist. The magazine was the perfect home for Szymin since it assigned him to cover stories that suited his political and social views.

Because his surname was difficult to pronounce, Szymin assumed the byline of CHIM (pronounced ‘shim‘ and written in all caps). Although it was meant to be a byline it became his name, both by his employers and his friends. “No one called him [by his name],” said fellow photographer Burt Glinn. “We called him Chim, Chimou, Chimsky, Chim-Chim.” He would eventually anglicize his name; Dawid Szymin became David Seymour, but he was always Chim.

Chim immersed himself in the photojournalist’s life and quickly attracted new friends. On a bus he noticed a young man carrying a sleek 35mm camera with dark tape covering the shiny metal parts–the photographer Henri Cartier (before he began to call himself Cartier-Bresson). They established a close friendship, which was soon joined by André Friedman (who soon thereafter took the name Robert Capa). They all shared similar views, similar politics, similar interests, similar passions, and held similar hopes for the future.

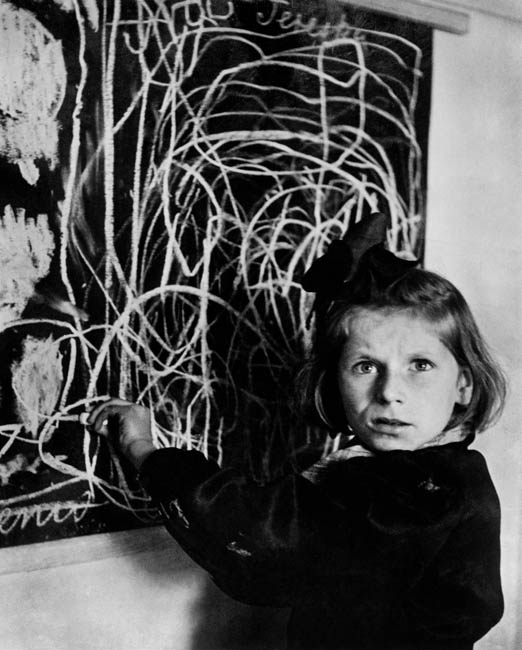

When civil war broke out in Spain Regards sent Chim to report on it. Unlike his friend Capa, who relished being on the front lines, Chim preferred to report on the effects of the war on ordinary people. His work was generally less adventurous and more thoughtful and compassionate. That said, when he found himself in or near combat Chim never shirked or faltered. Despite the fact that he was small, pudgy and wore thick glasses, he took the photographs the story required even if it meant putting himself at risk.

Chim covered Spanish Civil War until the end. In 1939 he traveled to the United States on his way to cover a story in Mexico. When he arrived in New York City he found that Germany had invaded his native Poland. The Second World War had begun. He cancelled his plans to go to Mexico. Since he had no work permit, Chim wasn’t allowed to take a job in the U.S. However, the law did not prevent him from becoming an employer. He and a Berlin photographer, Leo Cohn, opened a darkroom on 42nd St. (opposite the NY Public Library). It soon became a popular gathering place for freelance European photographers who were shooting for magazines headquartered in New York.

When the U.S. entered the war, Chim tried to enlist. He was eventually accepted by the Army, who trained him as an aerial photo-interpreter to decipher aerial photographs to determine what intelligence could be gleaned from them. Before being shipped overseas Chim legally changed his name to David Seymour, partly because he thought it sounded less Jewish and partly because he was concerned that somehow his parents might be punished if the Nazis discovered their son was serving in the enemy military.

Chim landed in Normandy shortly after D-Day and traveled with the 12th Army all the way to Paris. There, in one of those odd coincidences, he met his old friends Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. They talked about the future and made plans to open their own photo agency after the war.

The war ended eventually, and Chim was mustered out. He accepted an assignment for a U.S. magazine to shoot photographs for a story called We Went Back, about post-war Europe. While there he also hoped to determine the fate of his family, most of whom had disappeared in the Warsaw Ghetto. Although one of his sisters survived, he was never able to fully determine where or how his parents died. He was in Germany in 1947 when he received a short cable from New York: You are vice-president of Magnum Photos Inc.

Robert Capa had taken the plans they’d made in Paris and put them into effect. There were four founding members–a Hungarian (Capa), a Frenchman (Cartier-Bresson), an Englishman (George Rodger), and a Pole (Chim). They’d created an international agency that between the members could cover the entire globe. Unlike other photo agencies, Magnum was (and still is) owned and administered entirely by it members. The photographers chose their own assignments and retained all copyrights to their own work. By pooling their resources, they were individually able to select assignments that might not be quite as profitable.

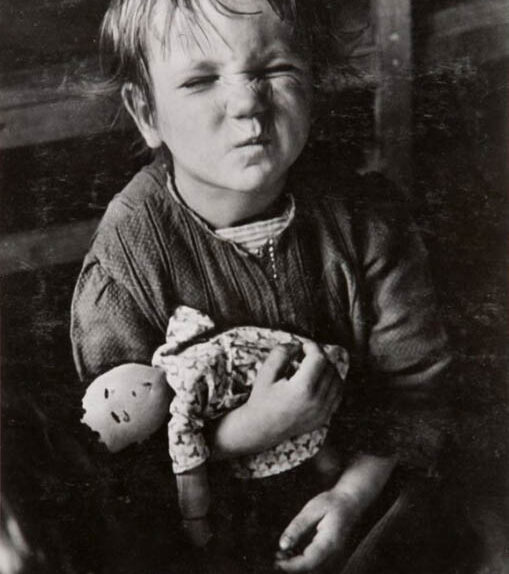

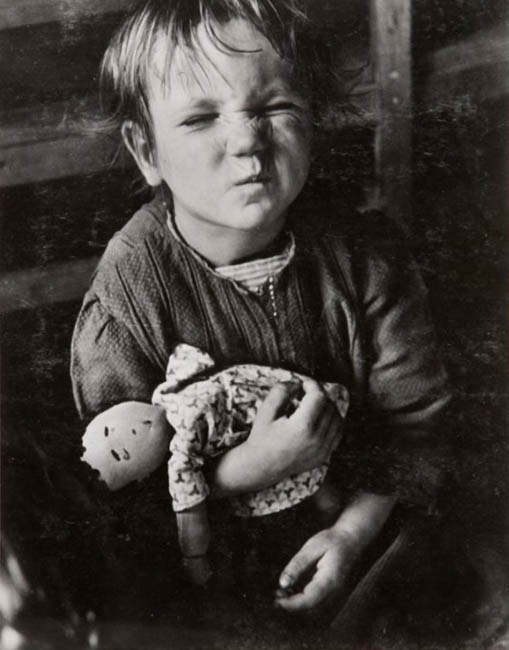

The advantage of this became quickly apparent. In 1948 Chim was asked by the newly-formed United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) to shoot photographs for a book on Europe’s children in need. The U.N. could not afford Magnum’s standard rate of US$100 a day, but Magnum accepted the assignment anyway. Chim traveled all over Europe and the Balkans. The photographs collectively were referred to as “Chim’s Children.”

Chim not only worked as a photographer, he was also in charge of the convoluted finances of Magnum. He found ways that not only allowed the photographers to accept assignments they wanted, but actually made them profitable. Two more photographers soon joined the cooperative, an Austrian named Ernst Haas and a Swiss citizen, Werner Bischof.

By 1953, five years after it was established, Magnum had established itself as the premier photojournalist agency. Although they maintained an office in New York City, the photographers were rarely there. In May of 1954 Bischof was on assignment in the Andes when his car went off a mountain road, plunging into a gorge and killing all passengers. Nine days later, Robert Capa, on assignment in Vietnam, stepped on a land mine and was killed.

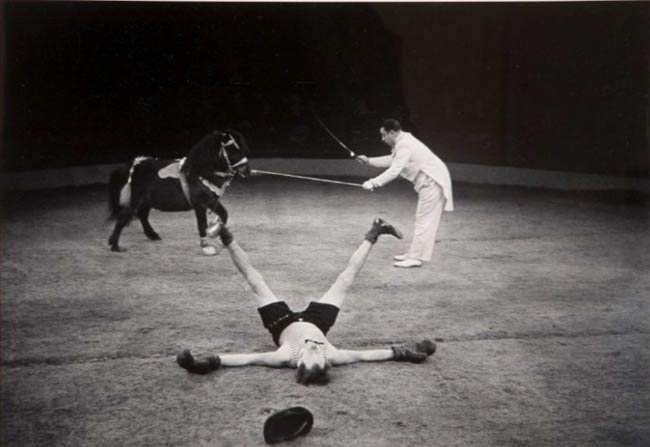

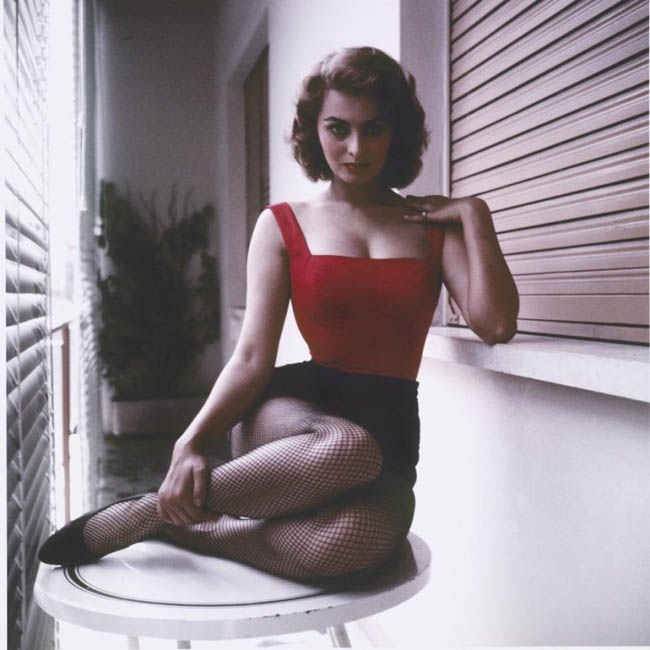

Chim suddenly found himself as president of Magnum. One of his first acts was to require all the members to make a will. He also insisted on continuing to expand the stable of photographers and their areas of expertise. To keep the agency financially sound, which allowed its members to periodically choose assignments that weren’t profitable, he encouraged the members to expand their range beyond news to entertainment and travel. Chim himself accepted assignments to photograph up and coming movie stars, such as Sophia Loren and Joan Collins. But his primary interests were always humanitarian. He spent a lot of his time in Italy and Greece and the new state of Israel.

In 1956, two years after the deaths of Capa and Bischof, Magnum had a total of thirteen members. Chim found himself in Greece without an assignment. A revolution was building in Hungary, and although he briefly considered covering it, he knew he was not the right man for the job. He was forty-six years old, portly, with bad eyesight, and he hadn’t covered combat since the Spanish Civil war nearly twenty years earlier. Another photographer was sent to cover Hungary.

At the same time, however, Egypt had decided to nationalize the Suez Canal, essentially closing it to Israeli ships and any ships bearing cargo to or from Israel. This led to a short but violent military action by forces of France, England and Israel against the Egyptian military and Arab forces. There being nobody to cover the conflict for Magnum, and being in nearby Greece, Chim went. He covered the story professionally, impressing other reporters with his concentration behind the camera. Reporter Frank White said, “Ben Bradlee and I made no secret of the fact that we were scared to death. But Dave, the quiet rational man, the intellectual, said nothing. He just kept on making pictures. When making pictures he seemed to be an entirely different man. I got the impression that he felt this made him somehow impervious to risk.”

And it seemed to work. Chim got the photographs. When the conflict ended and an armistice was declared, he gave his unprocessed film to Bradlee (who later was to become famous for his role as editor of the Washington Post during the Watergate era) to take back to Magnum headquarter. Chim said he wanted to stay behind and cover an exchange of prisoners.

Four days after the armistice, Chim and French photographer Jean Roy were driving a Jeep they’d liberated from retreating Egyptian forces, heading for the exchange site at El Quantara. They passed through the Anglo-French checkpoint without incident. As they approached the Egyptian forces, a nervous gunner opened fire. Both Chim and Roy were shot and their jeep plunged into the canal. Their bodies weren’t recovered until later. It was ten days before Chim’s 45th birthday.

Chim was the most moderate and gentle of the Magnum founders. He knew conflict needed to be covered and reported, but he took no pleasure in it. He considered himself a craftsman, though he encouraged his fellow photographers to make art. He left behind no wife and no children of his own. But his legacy includes unforgettable images depicting the lives of people much like himself, people who suffered because of the actions of governments. Most important, perhaps, is the legacy of Magnum Photos, Inc.

Ten years after Chim’s death, Henri Cartier-Bresson said this of his old friend: “Chim picked up his camera the way a doctor takes his stethoscope out of his bag, applying his diagnosis to the condition of the heart; his own was vulnerable.” It’s a fitting epitaph.