Phil Borges was your basic yuppie. A successful orthodontist, socially conscious, politically liberal, he traveled widely to remote areas of the world for pleasure and toted along an expensive camera to record his travels. Like a lot of enthusiastic hobbyists, Borges started taking some photography classes at his local community college. He didn’t have a unique photographic ‘voice’ and he wasn’t interested in any particular style of photography; all he had was very good equipment and passion.

Eventually one of his instructors made a suggestion that set in motion an improbable series of events. The instructor told Borges to look through magazines and tear out the photographs that attracted him. He was to pin those photos to a bulletin board, someplace he would see them routinely. Unlike most students, Borges actually did it. And hey, it worked. He noticed that most of the photos that ended up on the bulletin board were black and white portraits. So he began to combine his travels with his newfound interest in black and white portraiture.

At the age of 45, Borges did what so many of us wish we could do. He gave into his passions. He abandoned his orthodontics practice, moved to Seattle, and called himself a photographer.

His plan, apparently, was to combine his passion for traveling to remote parts of the world with his passion for photography. That certainly would have been enough to satisfy most people. At some point, though, Borges’ social consciousness asserted itself. He decided to take a radical approach to fine-arts portraiture; he would use it as a force for good.

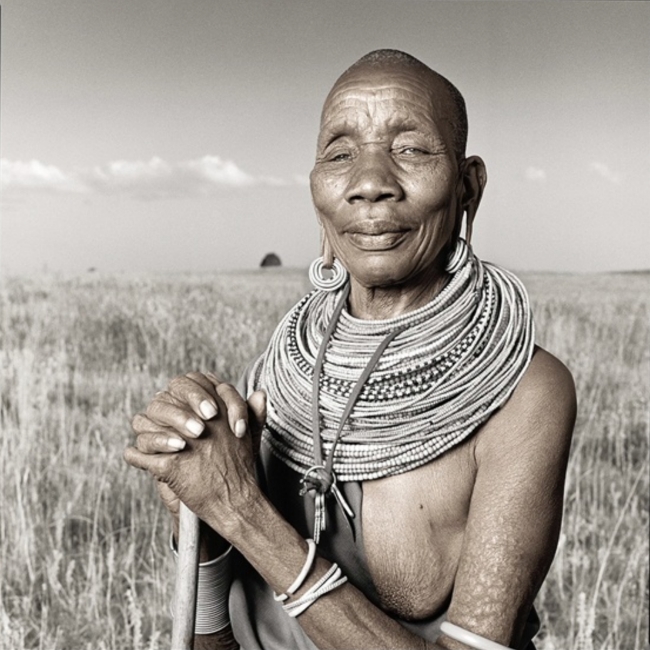

There’s something wonderfully quixotic about the notion of portraiture as a positive force for social change. It seems so improbable–and yet Phil Borges has made it work for twenty-five years. He has used his camera in the service of a variety of marginalized cultural groups…Tibetans under Chinese rule, women in developing countries, animist tribes whose territory was being encroached on by civilization, indigenous and tribal peoples whose ways of living are disappearing.

The portraits Borges produces are quite stylized. Over time he realized he wasn’t entirely happy with shooting strictly in black and white, yet he didn’t really want to make color portraits. He began to selectively hand-tone his prints in the darkroom, a laborious technique. Now, of course, he relies on Photoshop. The result is distinctive and instantly recognizable.

Borges’ approach is made still more idiosyncratic by his refusal to use individuals as a representative samples of the culture he’s examining. He insists on treating his subjects as individuals with unique life stories, though those stories can truly only be understood when seen through a specific cultural lens.

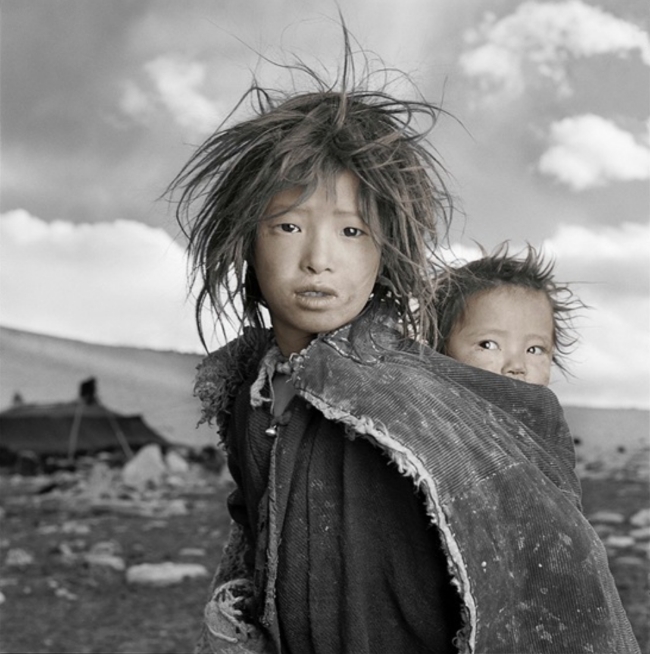

The preceding photograph, for example, shows two sisters–Jigme and Sonam–who belong to a nomadic family living in a remote part of the Tibetan plateau (which seems almost an oxymoron). Jigme had never seen a camera before, never seen a photograph of herself, never even seen her own reflection in a mirror.

“When I gave Jigme a Polaroid of herself, she looked at it, squealed and ran into her tent.”

Borges takes great pains to get the viewer to see this as a portrait of Jigme and Sonam, not simply as two generic nomadic Tibetan children. Yes, they belong to a community and a tradition that is rapidly disappearing for a variety of reasons–the Chinese government’s practice of encouraging Chinese nationals to move to Tibet, globalization in general, exotic ‘extreme’ tourism. But they are still just two young girls living the only life they know. The question is, how long will that way of life continue?

In 1994 Borges traveled to Nepal, northern India and Tibet to record what was happening to Tibetan culture. Two years later he began a study of animist cultures and their shamans. In 1998 he worked with Amnesty International on an exhibit and a book celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. By 2004 he partnered with the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE…the originator of the ‘care package’) to document examples of women empowering themselves in underdeveloped nations.

“I am always attracted to beauty as I see it. The beauty in the human face and the human form…. But more and more, my work is being driven by story, by issues.”

Borges comes by his social activism naturally. He grew up on a ranch in Utah and has always found himself “especially attracted to people that live close to the land.” That sort of life inevitably leaves its mark on faces and bodies. It ages people in a very specific way, weathering and lining the skin.

“In the beginning I was just attracted to the beauty of these people when photographing them, and then as I got into that I started learning more and more about the challenges they faced, and I became an advocate for them.”

Borges not only acts as an advocate; he’s also an educator and a facilitator. He is the co-founder of the Blue Earth Alliance, a foundation that sponsors photographic projects that examine cultures and environments at risk. Borges also created a group called Bridges to Understanding, which serves as “a sort of laboratory for cross-cultural understanding.” The Bridges program links schoolchildren in underdeveloped nations (such as Kenya or Peru) with their peers in the U.S. The children are given digital cameras, computers, and the training to use them. They then record aspects of their own cultures and share them via the internet. Kids attending schools in the US can get a glimpse of the lives of kids living in remote parts of the world…and vice versa.

Borges makes no pretense at being an objective photographer; he has no interest in being a neutral or dispassionate observer. His work, however, ignores an important question. While it is certainly commendable to want to preserve ancient cultures that are becoming extinct, should we also consider the wants and desires of the younger generations living in those cultures?

Sitting in the comfort of our homes, looking at these photographs on our computers, we may find the notion of nomadic tribes living out primitive lives on the Tibetan plateau romantic–but we don’t have to live those lives. What, then, is the proper role of the advocate?

Consider nine year old Sasha, pictured above. She belongs to the Nanai people of Siberia and resides with her grandmother in a remote village on the Amur River (which is frozen for eight or nine months of the year). The Nanai are a shamanist culture. There are only about 18,000 of them left. Young Sasha speaks and understands very little of the Nanai language. She exhibits the traits the Nanai traditionally associate with a shaman, such as hearing voices and fainting. but she holds little regard for those traditions. Rather than learning to become a shaman, she would prefer to study math and watch television.

The desire of Phil Borges to preserve ancient cultures is laudable. His passion and concern for the people and communities he photographs cannot be doubted. But his photography also raises awkward, uncomfortable questions. What is best for the Nanai people? What is best for Sasha? If those two questions have different answers, which answer should take precedence?