I love Sylvia Plachy and her photography. I first became aware of her in the mid-1980s through the Village Voice, the free weekly ‘alternative’ newspaper distributed in New York City. The contents page of the Voice included a single black and white photograph, usually presented without any context–no caption, no connection to the contents listed, no relationship to the news of the week. Just the photographer’s byline: Sylvia Plachy.

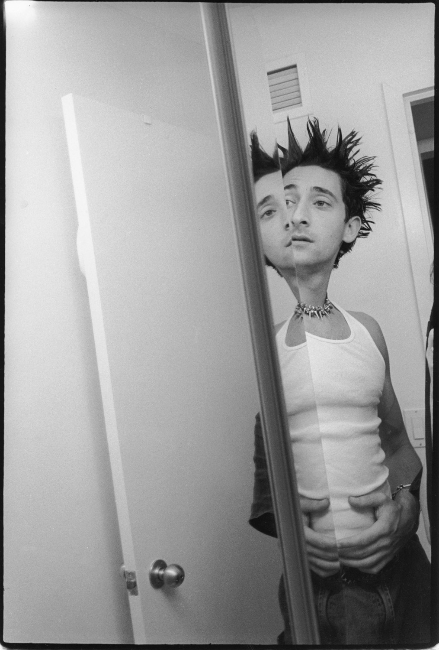

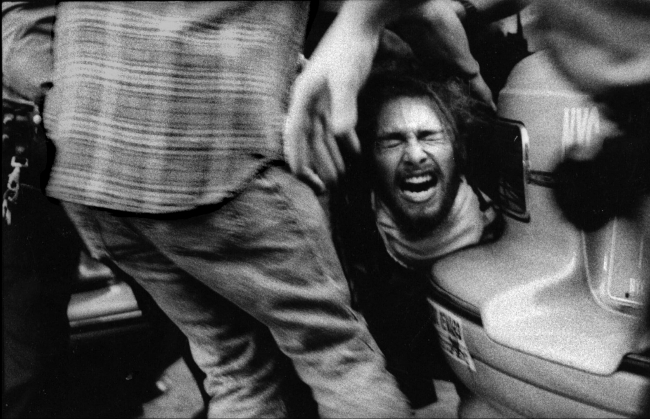

Her byline also appeared elsewhere in the newspaper, of course. She was one of the staff photographers, so she often shot the photographs that accompanied the articles and interviews. But it was that first photo on the content page that caught my attention. Sometimes it was straight street photography, sometimes it was an exquisitely tranquil still life, sometimes a portrait of an average New Yorker (whatever that is) or a famous writer or musician, sometimes a motion-blurred abstract, sometimes a goofy image of somebody’s pet, sometimes a political demonstration or street fair, sometimes just an image of one of the tens of thousands of gobsmackingly weird incidents that take place in the five boroughs every single day. If there was a recurring theme to the photographs on the content page, it was simple: this is life in New York City.

I didn’t always like the photo published on the content page of the Voice, but I loved knowing it would be there. It was always the first thing I looked at when I opened the paper; the first thing I looked at and the first thing I looked for. I’ve since discovered that the photo was simply Plachy’s most recent favorite, often something she’d noticed as she was wandering around New York going to or from an assignment. Those photographs were collected eventually and formed the heart of her first book, published by Aperture under the title Sylvia Plachy’s Unguided Tour.

She was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1943, during World War II. More than half a million Hungarians were killed during the war, including Hungarian Jews and members of the Roma community who died in the Holocaust. After the war Hungary was occupied by the Soviet Army; it became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. In October of 1956, a spontaneous revolution broke out against the Stalinist government. The revolt was brutally suppressed by the Soviet Army, resulting in major loss of life.

Plachy was 13 years old at the time of the revolution. A month after the rebellion was quashed, she and her parents concealed themselves in a farm cart that carried them to the border of Hungary and Austria. Hiding from the border guards, they crossed through a field of land mines into Austria. They made their way to Vienna and eventually to the United States. Like so many immigrant families, the Plachys settled in Queens, New York.

After graduating from high school, Plachy enrolled as an art major at the Pratt Institute. She took a photography course offered by Arthur Freed, and decided to become a photographer. New York City at that point in time was home to a number of Hungarian photographers who were (or would become) famous. Given that the post-war/post-revolution Hungarian community in New York was a rather tightly-knit group, it’s not surprising that one of those photographers would take an interest in a promising young student. In Plachy’s case, the photographer was André Kertész.

Kertész became Plachy’s mentor. He affectionately called her taknyos, which apparently means “snotnose” in Hungarian. “For the twenty years that I had the privilege of knowing him,” Plachy has said of Kertész, “I learned from him how to be a photographer. He passed on to me his tenderness toward his subjects and his love for the medium.”

Tenderness toward the world is not what one might expect from a child who grew up surrounded by war and revolution. It was, however, one of the things Kertész was known for. He once stated his first goal in photography was to express his feeling about the subject. Plachy undoubtedly would have made her mentor proud; regardless of the subject matter, her photographs radiate an aura of tenderness and affection. Above all, there is a simple honesty about her work.

Although her images often have a tilted perspective, although they may be blurry or strangely focused, those compositional elements never feel like a cheap trick or an intentional skewing of reality. They are simply the result of the spontaneity of her process.

“What makes you push the shutter has to do with seeking a kind of perfection, a harmony in the world. You are instinctively aware it’s there, but you’ve got to be completely alert and quick and so deeply awake that it moves you.”

Plachy’s work with the Voice brought her to the attention of other magazines and photographic venues. Her work has now appeared in more than 50 major publications. She has received numerous awards and fellowships; her photographs have been exhibited in galleries around the world and reside in the permanent collections of dozens of museums.

Despite all the fame and success, she continues to live in Queens and still works in the same way. She does not have an assistant, she avoids shooting in a studio, she relies on existing light. Whether working on assignment or just wandering the street, she carries her own camera bag. In that bag she keeps both b&w and color film as well as four cameras: a Holga (Plachy has been using the cheap plastic camera for more than two decades), a Hasselblad, a Leica, and a panoramic camera. “Each camera does something different,” she says. “What matters is how familiar you are with the equipment, so it’s just an extension of your eye and that you are free to follow your intuition.”

Plachy has been described as “a generous and unassuming photographer.” It is, I think, a completely accurate description. Her work contains none of the “gotcha” snarkiness seen in a lot of street photography. Her work can’t be said to be always gentle, but it is always embracing. Like her mentor, Plachy’s aesthetic seems to be shaped by her feelings for her subject–not her feeling about the subject, but for the subject. Whether the subject is her own family (her son is the actor Adrian Brody) or a stranger on the street or camels being herded into a theater for a Christmas musical, it’s clear she feels something for what she is photographing.

What makes this all the more remarkable is that she is able to communicate so much emotion without any affectation. Her work is simple, honest and direct. Richard Avedon said of her, “She makes me laugh and she breaks my heart. She is moral. She is everything a photographer should be.”

I love that observation: ‘she is moral.’ It may be a strange sort of compliment to give to a photographer, but it’s clearly appropriate. It may be that sense of morality is a result of her childhood. Village Voice writer Guy Trebay, who worked on assignment with Plachy, said “More than once it occurred to me that, when you are smuggled out of a Stalinist country in the bottom of a farm cart, covered with corn, at age 13, you have the sense that the worst has already happened.” That sort of experience could lead a person to see the world through a lens of suspicion–and that suspicion would be justified.

Or it could lead a person to experience every day with a sort of gratitude. The world can certainly be awful–and awful in innumerable ways. But it’s also full of delight and wonder and weirdness and astonishing beauty. And for that, we should all be grateful.

That’s my sense of Sylvia Plachy and her photography. It’s a constant, consistent expression of gratitude for simple, honest things. I love that she takes photographs with such insight and such grace and such passion. I love that she lets us see the world as she sees it.

I’m going to repeat what I said at the beginning of this salon. I love Sylvia Plachy and her photography.