Some lives seem more fiction than reality. Edward Sheriff Curtis lived that sort of life. He was born in Wisconsin in 1868, the son of a minister. Curtis’ father gave up the ministry when the family moved to Minnesota in the mid-1870s; he set up shop as a retail grocer. It’s unclear what sparked the boy’s interest in photography, but while in Minnesota young Edward built his own camera. He later became an apprentice in a local photography-engraving studio.

In 1887 the Curtis family moved again, this time to Port Orchard, Washington. Nineteen year old Edward purchased a store-bought camera and bought into an established photo studio. For the next several years he worked diligently as a portrait photographer; he got married, began a family and aside from short photo-expeditions, he settled down.

While shooting photographs around Seattle, Curtis met some members of the local Native American tribe, the Duwamish. He not only took portraits of them, he began to photograph them in their daily activities–fishing, digging for clams, making boats, etc. There was no indication at the time that this would eventually become his life’s work.

In 1898, while hiking and photographing Mt. Rainier, Curtis encountered a small party of scholars and scientists who had managed to become lost. Among the group was George Bird Grinnell, the editor of Forest and Stream magazine and an amateur expert on the Plains Indian tribes. Grinnell was intrigued by Curtis’ images of the local native tribes. He invited Curtis to accompany him on a pair of expeditions–one to Alaska and one into Blackfoot territory in Montana–to record the events.

His discussions with Grinnell and others convinced Curtis of the need to photograph the Native American tribes. At the end of the 19th century, American Indians were often referred to as a ‘vanishing race.’ Curtis became passionately interested in documenting their existence as thoroughly as possible before they ‘vanished.’ For the next few years, funded through the success of his photography studio and by prizes won in photography contests, Curtis amassed a large collection of images of various nearby tribes.

In 1904, one of those photography contests changed the course of Curtis’ life. He’d won top honors in the Ladies’ Home Journal ‘Prettiest Children in America’ contest. One result of that was an invitation from President Theodore Roosevelt to come to Washington, DC and photograph his family. Prior to leaving for DC, Curtis developed a lecture on North American tribes, incorporating some of the images he’d taken. He gave the lecture with great success in both DC and New York City. For the next two years, Curtis’s lecture series brought him a great deal of money. It was enough to fund further expeditions in the western U.S., but not enough to pay for the extensive project he had in mind. For that, he needed a philanthropist.

In January of 1906, Curtis arranged a meeting with J.P. Morgan. By the time the meeting was over, Morgan had agreed to pay Curtis US$15,000 a year for five years to conduct a thorough study of North American tribes, which was to be published in multiple volumes.

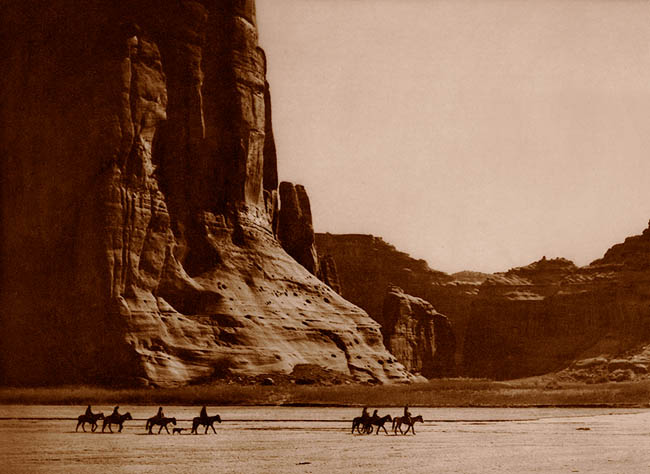

Initially, the project went well. The first volume of The North American Indian was completed in 1907. Curtis, however, wasn’t content to merely photograph the members of the various tribes and their activities. He also brought along equipment that allowed him to record the languages spoken by the tribes and their music on wax cylinders. He interviewed the people he photographed, gathering information on all aspects of their lives–religious ceremonies, funerary rites, construction of their homes and clothing, the food they ate and how they gathered it, the things they did for entertainment. He also recorded short biographies of many of the people he photographed, and in most cases these remain the only recorded histories of ordinary natives of that era.

As might be expected, the work was exceedingly difficult. Traveling to the tribal encampments with all that gear was cumbersome and slow, even by the standard of the day. It was also expensive. Sometimes Curtis worked alone, sometimes with assistants, all of whom needed to be paid. He also paid many of his subjects for the privilege of photographing them. Although $15,000 was a considerable sum of money in those days, it wasn’t enough. Curtis began to go into debt.

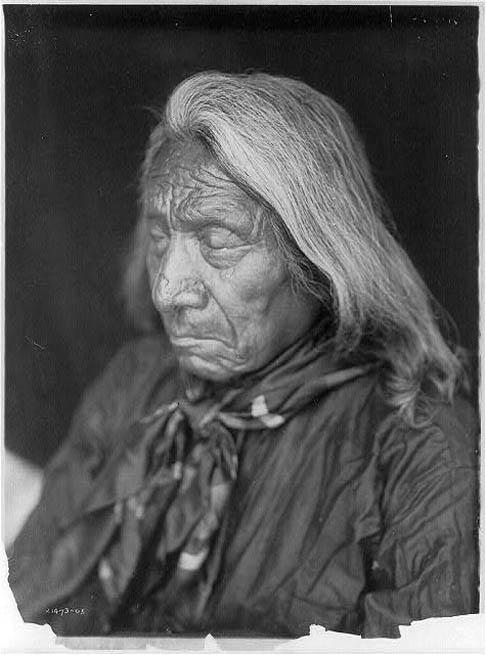

Even so, he was gaining national–and even international–attention, both for himself and for the so-called ‘vanishing’ tribes. Among some of the tribes he became known as “Shadow Catcher.” He not only recorded ordinary daily life in the tribes, he shot portraits of many of the most famous Indian leaders: Geronimo of the Chiricahua Apache, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota, who was one of the leaders of the Sioux who defeated General George Custer. These were names out of legend and the portraits shot by Curtis in this period seemed to link the legends to reality.

Because his work was so meticulous and painstaking–and therefore so very slow–only eleven of the anticipated twenty volumes had been completed by 1916 when America entered into World War I. The war turned the nation’s attention elsewhere. The public lost interest in the circumstances of the Native Americans. The funds began to dry up. Curtis went even deeper into debt.

That same year, Curtis’ wife filed for divorce. It took three years for the marriage to be dissolved, primarily because Curtis was rarely around to participate in the proceedings. In 1919 Clara Curtis was granted her divorce and was awarded the Curtis Photography Studio as well as all of her husband’s original negatives. Rather than see his ex-wife get custody of all the work he’d done to that date, Curtis went to the studio and destroyed as many of the glass negatives as he could.

The divorce didn’t interfere with his work for very long. Curtis was soon back in the field. Now that his funding had dried up, in order to pay for his project he was forced to periodically take work as a still photographer for the movie studios in Hollywood. He worked on such early classic films as Adam’s Rib and The Ten Commandments, as well as on the Tarzan movies.

The 20th and final volume of The North American Indian was completed and published in 1930, sixteen years after it was supposed to have been finished. In that time Curtis amassed over 40,000 photographs of more than 80 different tribes, as well as more than 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of tribal music, various languages, and first person accounts of daily life.

It was an extraordinary achievement. And nobody cared. The American public had not only moved on, the nation was entering the Great Depression. Fewer than 300 copies of the full 20 volume work were sold.

After nearly thirty years of travel, toil, worry, and exertion Edward Curtis was exhausted; physically, emotionally, and financially. He moved in with his daughter Beth in Los Angeles. Although he tried his hand at a number of different projects (including a period in which he mined for gold), Curtis never again achieved any level of success. He died at his daughter’s house in 1952 at the age of 84. The New York Times ran a six sentence obituary.

For years nobody saw Curtis’s work except ethnographers and anthropologists studying Native American tribes. Although they acknowledge a debt to his images of daily life, scholars in recent years have roundly criticized Curtis for reinforcing stereotypes and for misrepresenting reality. He is accused, correctly, of deliberately removing all signs of Western culture from his photographs and of glorifying the condition of the tribes at a time when they were actually living under increasingly squalid conditions. In effect, the scholars say Curtis may have actually harmed the welfare of the various tribes by representing their living conditions as better than they were. In addition, Curtis was known to encourage his subjects to stage scenes, and to have them dress in garb that was either historically inaccurate or garb that was reserved for special occasions. Rather than depicting the native tribes as they actually existed at the time, Curtis presented them as living relics of a noble past that no longer existed.

In the end, though, it cannot be disputed that Edward Curtis created a singular and historically valuable collection of images and recordings. He did so under incredibly trying circumstances and often to his own detriment. He carved himself a unique niche in American photographic history.