The aesthetic of landscape photography in the U.S. was shaped primarily in the West. This is the landscape of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston; it’s a landscape of open expanses, a primitive and pristine landscape, untamed and unspoiled. The land they photographed was unpopulated; there may be houses in these photographs, but no people. It was a wilderness, but a rather orderly one. The aesthetic reinforced the mythos of the American West. Beautiful. Manly. Unconquered and unconquerable.

That traditional Western landscape aesthetic came under challenge in the late 1960s and early 70s. A group of young photographers argued that the West portrayed in the images made by photographers like Adams and Weston no longer existed—if it ever did. They began to refer to that style of landscape photography as ARAT—Another Rock, Another Tree.

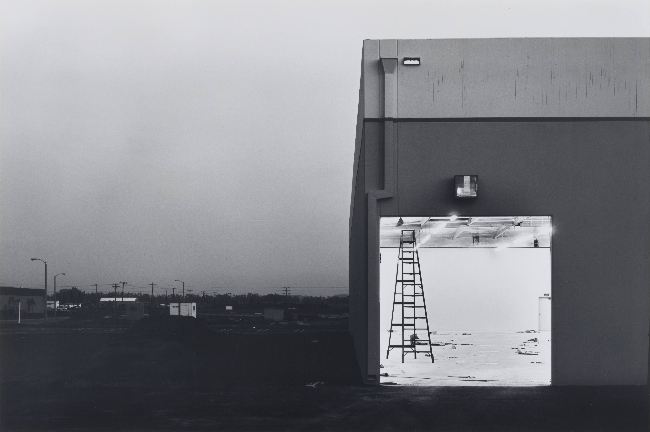

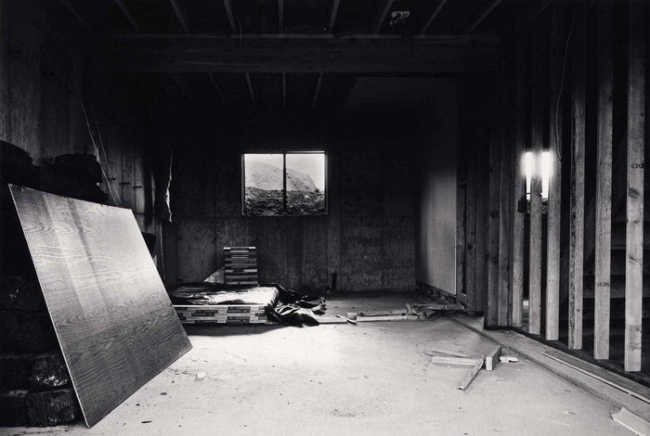

They began to develop a new Western landscape aesthetic. A counter-aesthetic that reflected the West as it actually was—or at least how they saw it. Where the old school treated the landscape with a sort of heroic sentimentality, they turned a dispassionate and unsentimental eye on the land. Where the old school portrayed the landscape as unsullied and virginal, the new school accepted the reality of a countryside transformed by human intervention. Where the old school created romantic images, the work of the new photographers was decidedly ironic.

This new aesthetic came to be called the New Topographic movement. One of the originators of the movement was Lewis Baltz.

Baltz was born in 1945, appropriately, in the new west—the west coast: Newport Beach, California. He seems to have decided to be a photographer at an early age. He received a B.F.A. from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1969 and an M.F.A. from the Claremont Graduate University. He’s been awarded grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. He’s earned an international reputation as an academic photographer.

Much of that reputation is a result Baltz’s early work with the New Topographic movement. In the mid-1970s he produced several series of photos depicting industrialized California landscapes. One of the characteristics of the New Topographic movement was to utilize the formal compositional elements of the traditional landscape aesthetic while turning other aspects on their heads.

For example, the traditional perspective was grounded in sweeping vistas with a distant horizon. The photographers of the New Topographic movement contended it was more accurate and representative to show the horizon interrupted, or even completely obscured, by man-made structures. Unlike the traditional aesthetic, which generally drew the viewer’s attention toward one dramatic point in the image, Baltz and his companions deliberately created images without any obvious point of focus. As is apparent from the photographs of the New Topographic movement, these photographers didn’t place much value on natural beauty.

Even when the New Topographic photographers embraced some aspects of the traditional aesthetic, they did so with irony. It was common for traditional landscape photographers to use foliage to frame the subject matter; the non-traditional photographers often used that same technique, though they tended to do so satirically. Occasionally they would reveal some aspect of the traditional aesthetic in an ironic or paradoxical way: a sign reading ‘Sand Dunes’ on a cinderblock building, the reflection of a palm tree in the window of an office building in an industrial park, a post-storm puddle in a parking lot offering a bizarro-world resemblance of a high mountain lake, the manufactured curve of a highway echoing the sinuous and organic curve of a river. Instead of the typically descriptive titles traditionalists used for their photos (such as Ansel Adams’ famous ‘Church, Taos, Pueblo’), Baltz often just included a mailing address.

At times, Baltz and the other New Topographic photographers shot photographs that employed the traditionalist tendency to present the landscape as unpopulated. Although the evidence of people is obvious, people themselves almost never make an appearance. The traditionalists imply that humankind either lives in harmony with the natural world or is absent from it. The new group declared that humankind has exploited and disfigured the natural world. If you want to see the landscape, look out the window.

Their ‘counter-aesthetic’ was as much an indictment of post-industrial capitalism as it was a polemic against the nostalgic romanticism of the traditional landscape aesthetic. If their photographs were seen as ugly, it was because ugliness had been inflicted on the landscape.

And let’s face it, their photographs were–and still are–seen as ugly by a large proportion of the photographic community. Even so, in 1975 ten of these photographers were given an exhibition at the George Eastman House, an exhibit curated by William Jenkins of the International Museum of Photography. The exhibition, entitled New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, had a profound impact on the photographic world. More importantly, the indirect repercussions of the exhibition have rippled through modern culture in wildly unexpected ways.

Not only did the arrival of the New Topographic movement on the art scene rattle modern landscape photography, it also helped spark a tectonic shift in popular culture. It was one of the first warnings about the increasing uniformity of man-made habitation. An industrial park in Irvine, California looked exactly the same as an industrial park in Cleveland, Ohio or Memphis, Tennessee. A strip mall in Elkhart, Indiana looks exactly like a strip mall in Troutdale, Oregon or Abilene, Texas.

The distinctive American landscape celebrated by Adams and Weston drew a marked distinction between nature and human culture. The New Topographic movement suggested that distinction was being destroyed. The American Capitalist Dream was in conflict with the American Landscape.

These days it’s not at all uncommon to see modern photographers exploring urban and suburban landscapes, to see photographers critiquing the altered landscape. Thirty years ago, it was a rare phenomenon.

I confess, I found it difficult to appreciate the early work of Lewis Baltz and the New Topographic movement. It’s so spare and unforgiving that it’s almost a sort of anti-art. Having spent an absurd amount of time looking at the photos and reading about Baltz and the movement, I understand this work better. I’ve come to respect the concept behind the movement. I can say it’s influenced the way I shoot photographs, but I can’t say I like the New Topographics in the purest form.

Maybe we’re not supposed to like it, though. Maybe we’re just supposed to let it influence the way we see the world. If that’s the case, then they’ve succeeded.