Nan Goldin once referred to photography as “the diary I let people read.” That sounds somewhat self-consciously artsy, the sort of thing you’d read in the Artist Statement of somebody in their first year of an undergraduate photography program. In Goldin’s case, however, it’s pretty damn accurate. This is a woman who has apparently never drawn any distinction between art, craft, and her own life.

She’s not the first person to collapse the barrier between art and life, of course. History gives many examples of artists who didn’t (or were unable to) separate how they expressed themselves and how they lived; artists like the painter Caravaggio, the dancer Isadora Duncan, the singer Janis Joplin, and scores of others. The biggest distinction is that Nan Goldin’s medium for expression–photography–allows her to easily record what was happening in her life and the lives of those with whom she was intimate.

Goldin’s self-focused style of photography has become relatively common now. Photographers like Wolfgang Tillmans and Ryan McGinley have produced similar work; images centered around their lives and the lives of their friends. But there are significant differences between their work and that of Goldin. They seem to purposely live lives about which they can make art; Goldin makes art out of the life she happens to live.

Nan Goldin was born in 1953 in Washington, D.C. and grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts–an upper middle class suburb of Boston. It was not a happy childhood. Her older sister, Barbara, committed suicide in 1965 by laying down on the tracks in front of a commuter train. Her sister’s death came after a series of hospitalizations apparently stemming from promiscuity (it was still relatively common then for girls who exhibited an ‘unhealthy’ interest in sexuality or expressed too much curiosity about ‘unnatural’ forms of sexuality to be considered psychologically unbalanced). Not surprisingly, Goldin was deeply affected by her sister’s experience.

Following the suicide, 14-year-old Nan Goldin’s life began to crumble. She ran away from home, she became sexually active, she began to drink and take drugs. She would spend the next few years in a variety of foster homes. In 1968, when she was fifteen, Goldin was enrolled in the Satya Community School, an alternative education program. One of her teachers gave her a Polaroid camera.

It seems obvious to mention it, but that was a defining moment. She became obsessed with the camera’s ability to record life, to record memories. For a troubled and alienated teen who felt unwanted by her family, the camera also offered a way for her to meet and interact with new people. “I used to call it a form of safe sex,” Goldin said.

After graduating from the Satya school, Goldin moved to Boston and enrolled in a photography program offered by the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in partnership with Tufts University. Her roommates during this period were two young drag queens, who introduced her to the gay and drag communities in Boston. It was during this period she began to shoot the type of photographs that would make her career. Goldin photographed her roommates with both honesty and affection. Their lives were complicated and difficult; “Normal people thought they were freaks,” Goldin said of her cross-dressing roommates, “gay men didn’t like them at all, and lesbians thought they were mocking women.” Her friends were happiest when talking about fashion or dressing up, but those were also the moments when they were most vulnerable–vulnerable to physical violence, to mockery, to self-loathing. But Goldin loved them and together they made a sort of family, a family at least as stable as the one she’d fled.

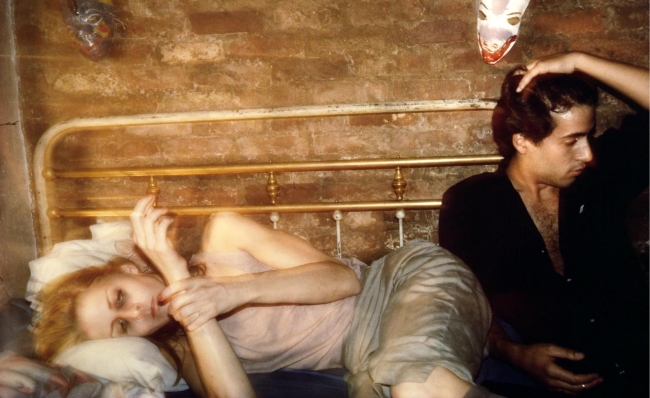

A year or so after graduating from college Goldin moved to New York City and became immersed in the post-punk party scene concentrated in the Bowery district. She tended bar to support herself, began drinking more and using harder drugs, became involved in the city’s gay and transgendered subcultures, partied with her friends and surrogate family. And, of course, she photographed it all.

Goldin occasionally exhibited some of her individual photographs in galleries, but that formal display didn’t suit her work. Her images had more power when displayed as a slideshow, and her natural arena turned out to be alternative venues like nightclubs and bars. Over time Goldin’s slideshow grew to around 700 images, to which she eventually gave the title The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The slideshow changed periodically depending on new events or people in Goldin’s life, but the core remained stable. It was a film document of a life unlike anything anybody had ever seen.

All this was taking place in the mid-to-late 1970s and early 1980s, an era novelist Tom Wolfe called the “Me Decade.” Notions of community, shared history, and human reciprocity had been discarded for a focus on the immediate needs and wants of the individual. People seemed to recognize, however, that Goldin’s work, while very personal, was not about herself so much as it was about the people she cared for. Her photographs were about her loosely organized tribe of hard-partying bohemians. While straight society was concentrating on “me,” Golden was concentrating on “us.” It was a severely dysfunctional “us” to be sure, but “us” nonetheless.

That awareness, along with the unposed artlessness of her photographs, drew the attention of art critics and Goldin began to become successful. With success came money, and with money came a larger and more extended surrogate family. Beginning in the early 1980s that family included a man named Brian, with whom she began a long-term tumultuous and destructive relationship, fueled by their desires and addictions: drugs, jealousy, alcohol, parties, sex and violence. It ended four years later in Berlin after Brian beat her so severely she nearly lost sight in her left eye. Goldin, as always, photographed everything.

In 1988, after ending her relationship with Brian, Goldin began a cycle of what has been described as “heavier drug abuse and vicious relationships.” She took relatively few photographs during the period, an indication of just how grim her life had become. She eventually entered a rehab program in Boston. As she regained some control over her life, she resumed photographing it. She did it with the same honesty as before. In rehab she even shot photos of her self-inflicted cigarette burns.

By the end of the 1980s, as Goldin was getting healthier, her surrogate family of friends was growing smaller. They were dying off–some from suicide, some from extensive drug abuse, but mostly from AIDS. Goldin, as might be expected, photographed her friends dying with the same straightforward honesty and nonjudgmental affection. Whether they were partying, sleeping, having sex, or dying, Goldin continued to photograph them.

By this time, Goldin was increasingly successful. Instead of living in a fourth floor walk-up coldwater flat in the Bowery, she had a fine apartment in New York and another in Paris. When she traveled she stayed in elegant hotel suites with balconies rather than hostels and flophouses. Instead of photographing her friends in decrepit rooms in anonymous buildings, she photographed them in rented beach houses and villas. But while the settings changed, the photographs remained stylistically the same. Or nearly so.

In her more current work Goldin has shown an interest in images that almost approach landscape photography–images without people. She has also begun to photograph families. Traditional families. Parents and children. Granted, the photographs themselves may not be entirely traditional. One such photograph (which I’ve decided not to show here) owned by singer-songwriter Elton John was the subject of a child pornography investigation (it was eventually deemed by the authorities not to be an indecent image).

Nan Goldin’s photographic style is generally included with the genre known as the “snapshot aesthetic.” It’s an informal style, deliberately innocent of the ‘rules’ of formal composition, lacking in pretense, even lacking in ambition. A snapshot doesn’t purport to be anything more than what it is on the surface: an artless document of a given moment in time. It’s commonly a moment in which people are enjoying themselves, but it can also be a moment the photographer simply feels ought to be recorded. A snapshot is most often shot using natural light, though if used with a flash the flash is usually harsh.

The snapshot aesthetic is a particularly apt description of Goldin’s work because snapshots are most commonly images taken of friends and families. She almost never photographs strangers. It’s also appropriate because of her willingness to shoot photographs in almost any lighting condition. The result is sometimes a blurry image similar to those shot by amateur photographers.

“I take pictures no matter what the light is. If I want to take a picture, I don’t care if there is light or no light. If I want to take a picture, I take it no matter what.”

No matter what. I like that attitude.

I appreciate the snapshot aesthetic, though I’m not particularly a fan of it. Which means I’ve never been much of a fan of Nan Goldin’s work. Until now. I’d always been exposed to her photographs in small doses–a few at a time. Looking at them in job lots, which is what I’ve done for this salon, is more in line with the format in which Goldin wanted them seen. A slideshow, so to speak.

I’ve come to appreciate her work much more. I’ve also come to appreciate her approach to photography much more, and her honesty. The photographs may not always lend themselves to individual scrutiny, but the entire body of her work is impressive. To my surprise, I’ve discovered I not only like Nan Goldin’s work, I like Nan Goldin.