In writing these salons I’ve noticed a commonality between many of the photographers featured. Time and again there seems to be a moment, an incident, a coincidence that sparks some sort of transformational shift in the person’s view of the world. Something happens that triggers the person to decide to become a photographer, to take photography seriously as a craft or art.

In the case of Hiroh Kikai, that transformational moment was an encounter with a friend of a friend.

Kikai was born in the small Japanese village of Daigo in 1945, at the very end of the Second World War. His childhood appears to have been unremarkable; he was no prodigy and there was nothing about him to lead one to believe he’d eventually become a well-known and highly regarded poertrait photographer. He attended Hosei University in Tokyo, where he studied philosophy. As a student Kikai took a serious interest in cinema, but doesn’t appear to have studied it formally. He has stated that he might have considered a career in film production, except that it required both money and some facility with writing, both of which he lacked.

After obtaining his degree, Kikai took a job as a truck driver (a degree in philosophy was clearly as marketable in Japan as in the U.S.). A year later he found employment as a dock worker in a shipyard. He continued, however, to stay in touch with one of his philosophy professors—Sadayoshi Fukuda. Fukuda wrote a regular column for a Japanese camera magazine, Camera Mainichi. In 19969, Fukuda introduced Kikai to the magazine’s editor, Shōji Yamagishi. Yamagishi happened to show Kikai some photographs by Diane Arbus.

That was the moment. Something passed from Arbus through Yamagishi and Fukuda to Kikai. He decided he wanted to learn photography. He didn’t even own a camera.

In one of those extraordinary coincidences, shortly after seeing the photos by Arbus Kikai came across a camera for sale. A Hasselblad 500CM with an 80mm lens. Although the camera normally sold for ¥600,000, the owner was willing to sell it to Kikai for only ¥320,000. Unfortunately, that was approximately Kikai’s monthly income. He mentioned the deal to his old philosophy professor; Fukuda promptly lent him the money to buy the camera. Kikai has been using it ever since.

It seems photographers in Japan, more so than in other nations, tend to join groups. Photography is often a communal activity. Not so with Kikai.

“I have always preferred working alone. People may think this is driven by…misanthropy: in [Japanese] society people that choose to work in this way are often the victims of prejudice. It is therefore a difficult way of life, but I think it can be a hugely valuable one.”

Kikai has also said he doesn’t like to look at the work of other photographers. “I am always concerned that I will be destabilized by the fact that some of them are much better than I am.”

He continued to support himself doing odd jobs for the next few years, including an eight month stint onboard an industrial tuna fishing boat. Although he managed to get a few photographs published, Kikai decided that in order to be a real photographer he needed to learn darkroom techniques. He managed to get hired by Doi Technical Photo in Tokyo, and from 1973-76 he was employed as a darkroom technician. When he felt he’d learned all he needed to, he quit and took a manufacturing job at an Isuzu plant.

During his tenure in the darkroom, Kikai began to create a series of informal portraits that have come to be called the Asakusa Portraits. On his days off, he would walk down to the Asakusa district of northeast Tokyo. Asakusa is something of an entertainment center—comedy theaters, geisha houses, a carnival complex, movie theaters that show classic Japanese films. Asakusa also appears to be a center for kitchenware and cooking supplies. Most importantly, though it’s the site of the Sensō-ji temple, a once-popular tourist and pilgrimage location that lost much of its status after the war.

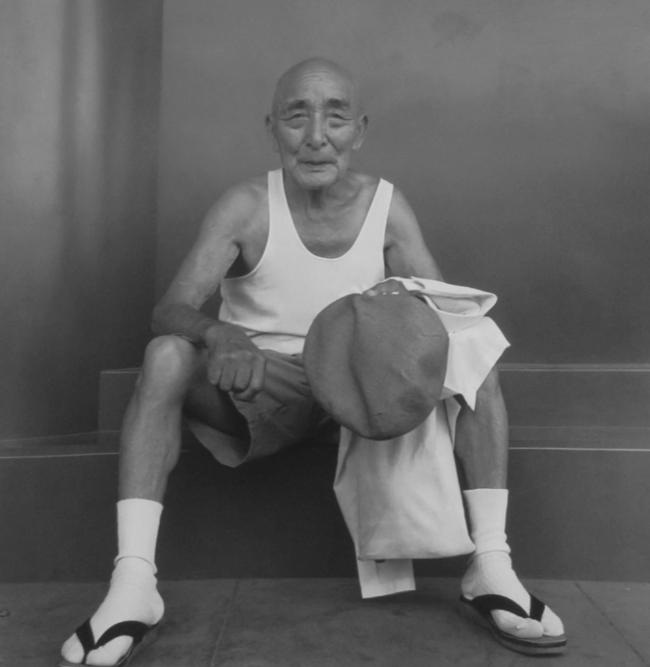

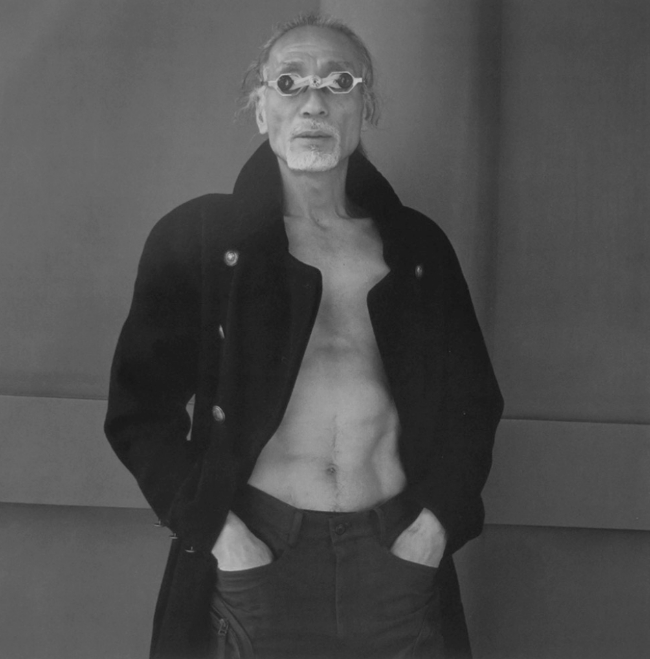

For more than thirty years Kikai has gone to Sensō-ji to photograph the people who visit. The portraits are all similar in style; a single subject standing or sitting in front of the red temple walls, usually looking directly at the camera. Kikai is very selective about his subjects, although he doesn’t appear able to articulate exactly what he looks for in a portrait subject.. He sometimes waits for hours to find somebody he wants to photograph; some days he’ll encounter two or three people he finds photogenic, some days he won’t shoot any photographs at all. Sometimes three or four trips to Sensō-ji will pass before he gets a single shot.

When he finds a likely subject Kikai approaches them, visits with them briefly—rarely more than ten or fifteen minutes—then asks their permission for the photograph and takes a few exposures. In this way he has photographed more than six hundred people at Sensō-ji.

Given his background in philosophy, it’s not surprising to learn Kikai’s approach to photography is thoughtful and intellectual. The essential thing in photography, he says, is the act of seeing. Not just looking, but seeing. Kikai says the “notion of ‘seeing’ is far less obvious than it seems. Looking is within everyone’s grasp; seeing is difficult.”

Obviously, Kikai tries to ‘see’ his subjects, not just look at them. Even though he has been photographing strangers in front of a certain wall at Sensō-ji for three decades, he maintains the location itself isn’t important. He just likes that red wall. The important thing is how he engages with the subject.

“It is this process of relating that makes a good photograph. It is not the place that matters—in fact, I started shooting there because it was not far from my home—it is the people.”

Kikai photographs these people with honesty, compassion, humor and affection…and it shows.

There is a universality to Kikai’s portraits, even though his subjects at Asakusa are predominately (or, perhaps, exclusively…I’ve not seen all 600 photos) Japanese. Their Japanese-ness is secondary or tertiary. He photographs his subjects as individuals, not representatives of any time or place. Some of them are ordinary people, some are just a wee bit out of true, and some are very clearly maladjusted.

These portraits work on two levels. Each photograph works beautifully as an individual portrait, revealing the surprising diversity of the visitors to Asakusa. But they also work collectively; all these people are part of a single community. Like Kikai himself, they belong in Asakusa.

By 1984 Kikai had become successful enough to quit his other jobs and support himself as a freelance photographer. He has since traveled widely in his career: India, Turkey, Cuba, the twenty-six nations of the European Union. Yet he remains best known for the simple portraits he takes at Asakusa.

When Hiroh Kikai was asked about those photographs of Diane Arbus, the photographs that sparked his career, he replied “I was surprised that there were photos out there that I didn’t grow tired of looking at.” I want to say the same ungrammatical thing about Kikai’s work. These are images I will never grow tired of looking at.