NUDES NUDES NUDES

There is a forlorn and tragic rhythm to the life of Czech photographer František Drtikol. Born in 1883 in Příbram, a mining town in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and is now the Czech Republic), Drtikol rose to become a prominent artist and famed portraiture photographer. He was an influential figure in an era known for its creative vigor. He created vivid images unlike anything anybody had ever seen. And yet when he died 78 years later, he was impoverished and virtually unknown.

Although it was primarily a center of mining, Příbram at the end of the 19th century had a small reputation for its artisans and craftsmen. The men who worked the mines (and their wives and children) often augmented their income through high quality craftwork, such as embroidery or woodcarving. Drtikol grew up with a desire to draw and paint. After a period of military service, he moved to Munich to study art.

Munich, at the turn of the century, offered an incredibly vital and fertile creative environment. This was the height of the Art Nouveau movement. Like almost all artistic movements, Art Nouveau was grounded in theory as well as practice. The underlying notion of the movement was that artists should bring their talents to bear on everything they create, no matter how mundane or utilitarian—whether it’s a sculpture or a footstool, a painting or a napkin-holder. In addition, artists needn’t restrict themselves to a single mode of design; a sculptor should be able to design a house, a painter should be able to design a lamp. This notion must have held great appeal to a young man who’d grown up watching miners create hand-crafted cribs and intricate embroidery.

In Munich, Drtikol focused primarily on drawing and photography. Photography as an artistic medium, it must be remembered, was very new and seen as a perfect example of modernity. It combined science and art, technology and intuition. After finishing his education, Drtikol moved to Prague. He completed a brief period of apprenticeship with another photographer, then in 1910 opened his own studio.

He quickly developed a reputation as a portrait photographer. His clientele included many of the most notable public figures of the day, ranging from captains of industry to political figures to famous artists and musicians. His subjects included Tomáš Masaryk, the first elected president of Czechoslovakia, and the composer Leos Janacek, and just about every artist living in or near Prague. Within a decade, his studio was famous throughout Europe.

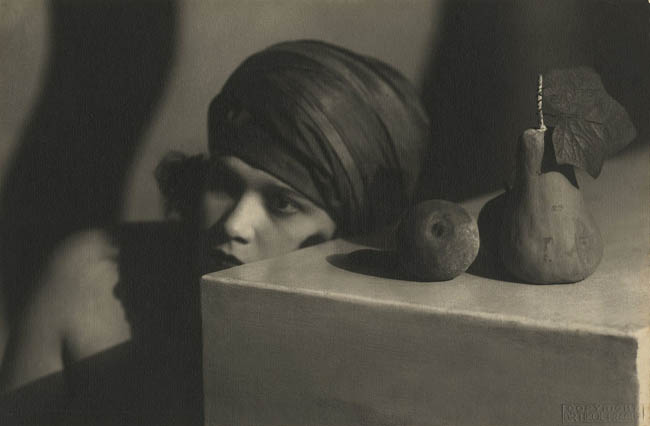

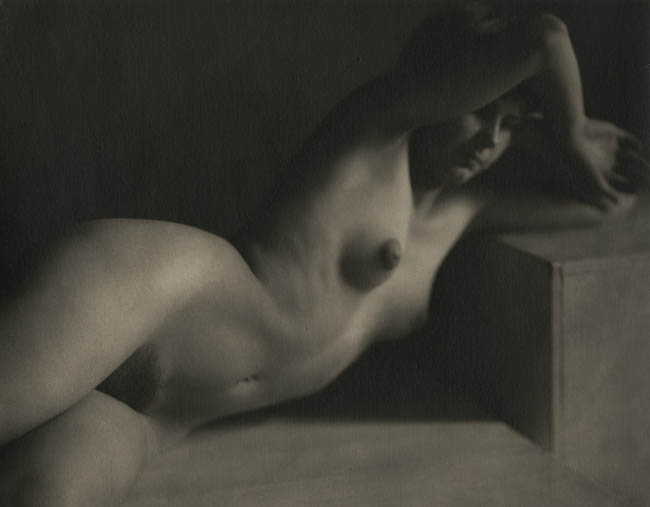

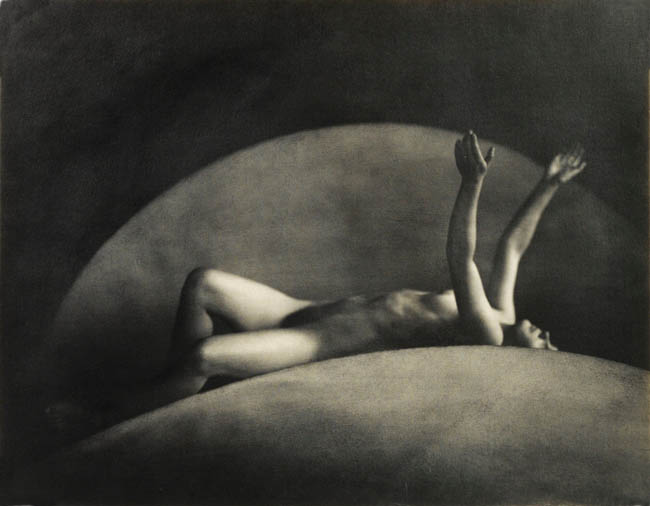

Portraiture was the means by which he supported his studio and made a comfortable living, but Drtikol made his name as an artist through his nude studies. His portraiture was elegant and refined, but his nude studies were daring and inventive. They were the epitome of avant garde. He was among the first—if not the first—photographer to incorporate the elements of Art Deco into his work.

Unlike Art Nouveau or other art movements, Art Deco had no philosophical or political underpinning. It was purely decorative. The Art Deco movement was based on geometric shapes influenced by wildly eclectic sources. For example, in Art Deco one can see the influence of the styles of ancient Egypt and Aztec art, and of the contemporaneous engineering notion of ‘streamlining,’ and of mathematical concepts emphasizing reiteration of shape and form.

“I am inspired by three things: decorativeness, motion, and the stillness and expression of individual lines.”

He frequently contrasted the suppleness and flexibility of the female body against solid and unyielding geometric forms. Despite those differences, he emphasized the strength to be found in both forms, human and geometric. And yet it’s never entirely clear whether the geometry is echoing the body, or the body is echoing the geometry. The implied motion of the body is, perhaps, the characteristic that most distinguishes one form from the other. He placed those forms in settings of deliberate, studied simplicity.

“I let the beauty of the line itself make an impact, without embellishment, by suppressing everything that is secondary.”

Drtikol’s approach essentially transformed the genre of classical nude photography. Most artists who worked in nude studies—painters and sculptors, as well as photographers—had concentrated on the body. Drtikol wrote of this as “nakedness as beauty itself.” However, for him the nude body was just one element of the work; it had to work in coordination with the other elements of the composition.

Drtikol showed a willingness to incorporate anything that might make his nude studies more powerful. In addition to the inclusion of Art Deco details, he used lighting techniques developed for the new medium of silent movies and integrated elements of modern expressive dance. He synthesized the modern and the classical, and the results were startling. Nobody had ever seen anything like it.

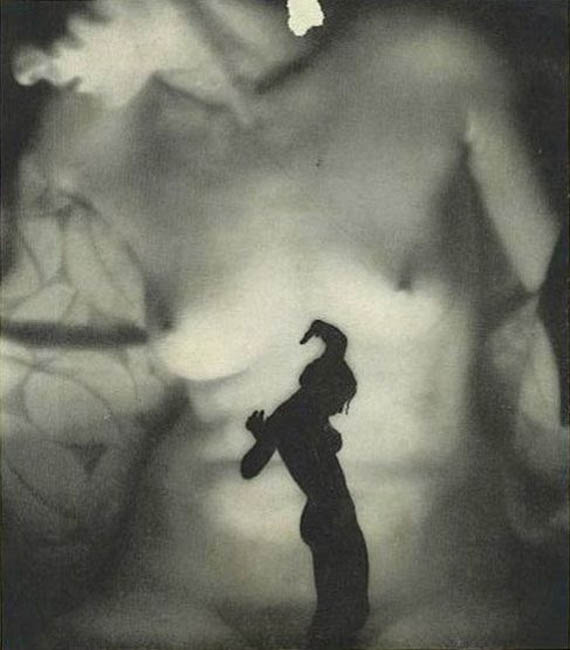

And yet it wasn’t quite enough. Eventually Drtikol decided the human body wasn’t quite malleable enough for his imagination. In 1930 he began to eliminate the living body from his work. Instead, he began to cut human-shaped forms out of stiff paper and shape his work around those.

Around this same time, Drtikol became intrigued by Buddhism thought and practices. Between the shift in his philosophy and the freedom that came from abandoning the body, his work took on a more spiritual and ephemeral quality. Many critics also feel the work became more erotic as it became more abstract. Drtikol himself remarked that for the first time he was truly happy with his photography.

That happiness lasted a mere five years. In 1935 Drtikol abruptly stopped shooting photographs. The worldwide economic depression of that era surely played a role in the decision to close his photography studio in Prague, and it may explain why he sold all his prints, his negatives and his glass plates…but it doesn’t account for his decision to give up photography and begin painting again. Although he occasionally gave lectures on photography or composition, Drtikol never again took up the camera.

He gradually drifted into obscurity. His work fell out of fashion. He became impoverished. By the time of his death in 1961, Drtikol was essentially a hermit; few people knew who he was. It wasn’t until a decade or so after his death that art historians began to re-examine his work and his role in shaping modern photography.

František Drtikol’s life was certainly as dramatic as his art, and his art was as inventive and creative as anything anybody of his time had ever seen. It may seem dated to our modern eye, but even now we can recognize the astonishing originality of the work.