He was born in 1941 in Wells, Somerset in the Southwest of England, where he was given the unfortunate name of Holroyd Anthony Ray-Jones. His father, an engraver whose work was collected by the British Museum, died when he was only eight months old, after which his mother moved the family to London. At some point, he mercifully abandoned the name Holroyd. He’s known to art historians, critics and students of photography as Tony Ray-Jones.

When he was still in his teens, Ray-Jones enrolled in the London School of Printing where he studied graphic design. He learned to use a camera primarily as a tool to aid him in his design work. It wasn’t until his third year in the program that he bought a good camera—a Rolleicord.

Ray-Jones took that camera with him during a holiday in Algiers and shot a series of photographs from a taxi. He included some of those photographs with an application for a scholarship to a two-year MFA program in design at Yale in New Haven, Connecticut. He was awarded the scholarship and in 1961, before his 20th birthday, left England for the United States.

In the U.S. Ray-Jones discovered a radically different attitude towards photography. In England of the late 1950s photography was taught as a craft or a useful commercial tool, rather than as an artistic medium. In the States—and most particularly in New York City, just a short train ride from New Haven—he found photography was taken seriously as a means of expression. Although he still intended to make a career out of graphic design, Ray-Jones was caught up by the passion his instructors and fellow students felt for photography. That passion was stoked after attending a lecture given by Alexey Brodovitch—one of the most influential leaders of American design and art direction, and mentor to such photographers as Irving Penn and Robert Frank.

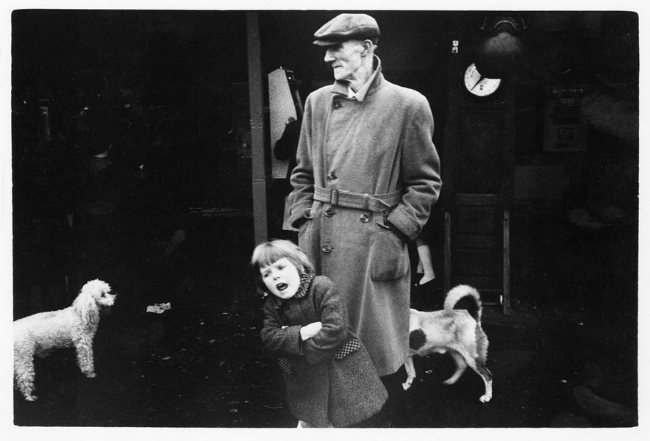

After completing the first year of his two-year program, Ray-Jones convinced his advisors to let him take a year off to attend workshops given by Brodovitch in New York City. Those workshops took place in the studio of photographer Richard Avedon. It was during this period that Ray-Jones met Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand, who introduced him to the concept of street photography, which was still a relatively new frontier in art photography.

Ray-Jones traded in his bulky Rolleicord for a new, lightweight 35mm Leica and put himself out on the street. “Every Saturday there would be ethnic parades,” Meyerowitz said of that period. “St Patrick’s day, Polish day, Columbus day, veterans’ day. We used these parades as a laboratory. We learned to be invisible. We learned how to shape pictures that were not about an event but about an observation.” Ray-Jones absorbed the aesthetic of street photography and was changed by it.

At the end of his year in New York City, Ray-Jones returned to Yale and completed his MFA in design. There was no doubt in his mind, however, that his future now lay somewhere else. He’d become a photographer.

After graduation, Ray-Jones returned to New York City and worked briefly as an associate art director for Brodovitch’s Sky magazine. He also took a few freelance photography assignments for magazines like Saturday Evening Post and Car and Driver. When he wasn’t working Ray-Jones was out on the street with his camera—often with Meyerowitz or other street photographers—developing his own photographic voice. But in late 1965 or early 1966 his visa expired and he was forced to return to England.

On his return Ray-Jones is said to have been dismayed to find no London photographers were practicing the hard-edged and aggressive style of photography he’d fallen in love with. There were, in fact, English photographers doing exactly that, but it appears Ray-Jones was simply unwilling to give them credit or acknowledge their work–not because it wasn’t good, but because they lacked his New York experience.

This was to become a pattern for him. He could be quite generous with his time and talent, but he could also be abrasive and arrogant. In 1968 the owner of Racing Pigeon, a magazine devoted to pigeon fanciers, decided to launch a new photography magazine, Creative Camera. Ray-Jones approached the magazine’s editor and told him “Your magazine’s shit, but I can see you’re trying. You just don’t know enough, so I am here to help you.” Instead of tossing him out on his ear, the editor agreed to look at his portfolio and eventually hired him as a consultant.

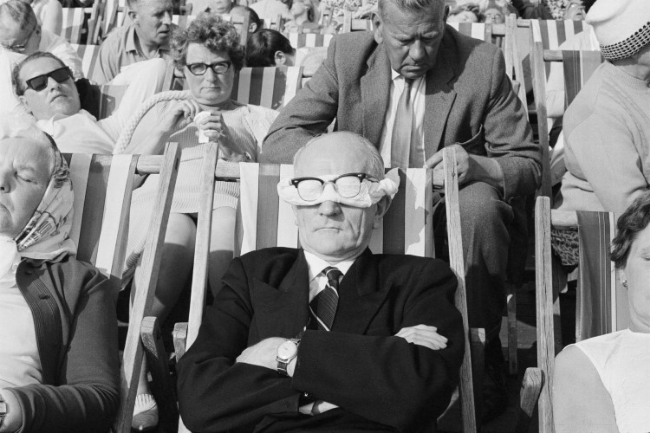

England, of course, isn’t the U.S., London isn’t New York City, and the English aren’t Americans. Ray-Jones realized that what had attracted him to street photography in New York was the unguarded and eccentric behavior of the people he encountered, not the streets themselves. He didn’t see the same sort of behavior on the streets of London. He did, however, see it at festival events and among his countrymen on holiday at the seashore. Ray-Jones decided to adapt the New York street aesthetic and apply it to local customs and habit. He would document the English—his own people—at leisure.

It’s a testament to his work ethic that Ray-Jones kept a journal with extensive notes on his thoughts and work process. One entry in particular reads like a primer for street photography:

- Be more aggressive

- Get more involved (talk to people)

- Stay with the subject matter (be patient)

- Take simpler pictures

- See if everything in background relates to subject matter

- Vary compositions and angles more

- Be more aware of composition

- Don’t take boring pictures

- Get in closer (use 50mm lens [or possibly ‘less,’ the writing is unclear])

- Watch camera shake (shoot 250 sec or above)

- Don’t shoot too much

- Not all eye level

- No middle distance

Ray-Jones didn’t always abide by his own tenets—what street photographer worthy of the name would? But this devil’s dozen principles are solid in terms of street photography doctrine.

Despite his work on the English seaside, Ray-Jones was eager to return to the United States. He managed to land a job teaching photography at the San Francisco Art Institute. In January of 1971, he moved back to the U.S. with his wife. He disliked teaching and he disliked his students—he found them lazy, spoiled and self-centered. He also he found his own energy lagging. In February of 1972, he consulted a doctor and was diagnosed with a particularly vicious form of leukemia. He and his wife returned to London, where he died a month later.

Those are the facts of his brief life. We so often view such facts through a lens that filters out history and culture. Why did Ray-Jones find the U.S. so much more interesting and vital than his native England? Part of it was novelty, of course. A foreign place is usually more stimulating than a familiar place. Part of it was probably the contrast between British reserve and American brashness.

But it’s also important to remember that Ray-Jones was born during WWII. The cultural differences between England and the U.S. were magnified by the fact that for Americans the war was shorter and fought on other continents half-way around the world. Americans didn’t see their cities bombed. It also matters that Americans believed that they won the war, that without their intervention, the wars in Europe and Asia would have been lost. Regardless of the validity of that belief, it colored the post-war attitudes of both cultures. That strange combination of swagger and cowboy individualism had to be attractive to an English boy born only a couple weeks after the end of the London Blitz.

That Ray-Jones brought that brashness back to England with him shouldn’t be surprising. He returned to his native home toting his camera like a six-shooter. Although other English photographers were also working in the New York street tradition, Ray-Jones saw himself as the new sheriff in town. And he behaved that way, determined to kick ass and take names—and he did, he surely did.

Little of Ray-Jones’ personal work was exhibited during his lifetime. But as is so often the case, shortly after his death the work began to be appreciated. He is now generally credited with bringing the street aesthetic to England. That may not be entirely accurate, but there it is. Many of the current generation of British documentary/art photographers (including Martin Parr) were inspired by his work. “His pictures were about England,” Parr has said. “They had that contrast, that seedy eccentricity, but they showed it in a very subtle way. They have an ambiguity, a visual anarchy. They showed me what was possible.”

Tony Ray-Jones may not have single-handedly changed the nature of British photography, but he acted like he did. And in some ways, that’s the same thing.