Los Angeles. Unlike Paris or New York City or Prague, the city of Los Angeles has a reputation among photographers for being notoriously difficult to photograph. That’s because LA exists as much in myth as in reality. It lacks a single identity. LA is the city of Raymond Chandler and Rodney King, it’s the city of water wars and Hollywood, of the Watts riots and the Watts Towers. LA is home of the car chase, the city of OJ and the White Bronco, a city of highways so convoluted they make the human circulatory system seem simple. LA is James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause and N.W.A. with Straight Outta Compton. It’s a city of palace gates and chain link fences, where the weird is commonplace, and everybody is on the move. Los Angeles is a chameleon that changes its shape as well as its color.

It is, of course, a city of contradictions. Wild contradictions. Is LA is an example of careless ecocide or a land of constant renewal? Is it a pre-apocalyptic warren of 4th generation urban warfare between rival gangs or the rapier point of pop culture? Is it a place of immoderate blandness or a postmodern prison factory? Is it an example of American apartheid or a haven for immigrants? Utopia or dystopia?

Los Angeles is probably all of those. Include the fact that city itself extends to around 500 square miles (or nearly 4000 square miles if you ignore municipal borders—and LA has always had a rather elastic interpretation of borders), and it’s no surprise that the city has been difficult to photograph. Perhaps the only way to approach Los Angeles as a photographic subject is to treat it as a sort of consensual, communal hallucination.

That brings us to French photographer Guillaume Zuili.

Guillaume Zuili was born in Paris in 1965. He seems to have been drawn to both photography and urban landscapes from a young age. He was a professional photographer by age 21. He became a member of the well-known VU agency in 1992, when he was only 27—the same year his first book of photographs was published.

In the middle 90s Zuili began to create a series of photographs based on the notion of the city as a repository for memory. He spent a decade photographing Berlin, Moscow, Prague and Lisbon, as well as his native Paris, creating a series of subtly complex double exposures. The layered images were suggestive of the layers of each city’s unique history. The double exposure approach, according to Zuili, forces the moment the shutter is released to become both “significant and irrelevant, as well as public and private, very much like history itself.”

In 2002, he moved to Los Angeles as a correspondent for the VU agency. His approach to urban photography underwent a radical shift. His earlier urban studies had been grounded in history. LA is a city that, despite having a long and fascinating history, sloughs off its history as easily as a snake shed its skin. As a result, Zuili treats the LA mythos as if was history.

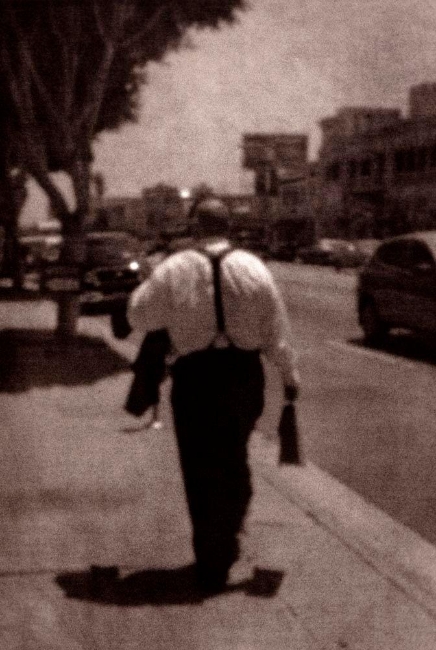

Zuili’s Los Angeles is a hybrid city. It’s both modern and old—or what passes for ‘old’ in LA. His photographs of LA depict the present day as if its seen through a 1940s Raymond Chandler whiskey haze. The photographs manage to feel both gritty and dreamlike. LA may be carelessly casual about its history but it’s a city full of memories, some of which are real. Zuili is able to present a hard-boiled realism that can’t be completely obscured by the indistinct edges of memory.

Chandler, through the character of his private detective Philip Marlowe, called Los Angeles “lost and beaten and full of emptiness.” Zuili gives that to us. In one of the most populous cities of the world, Zuili gives us empty or near-empty streets. He makes us feel the truth of Marlowe’s statement while convincing us that it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because in Zuili’s LA nobody notices that they’re lost or beaten. If the city looks full of emptiness, it’s the emptiness of a stage just before the action begins.

These are clearly Chandler’s mean streets, banged up and shabby as an old fedora. But you can’t escape the romanticism that infuses Zuili’s photographs. Sure, it’s a cheap grifter’s sort of romance, a bit tarnished and with most of the shine taken off, but it’s inescapable all the same.

Zuili’s approach is perfect LA. He photographs a hybrid city with a hybrid technique. He takes snapshots with a pinhole camera. Think about that for a moment. Snapshots. With a pinhole camera. It’s…I want to say ‘crazy’ but I’ll settle on ‘counter-intuitive.’

Snapshots, by definition, are the result of snap decisions. The photographer sees and shoots, with relatively little thought given to the more formal notions of composition. The camera is a conduit for the photographer’s eye. The snapshot aesthetic owes as much to intuition as to art—that’s what gives the genre of snapshot photography much of its vibrancy.

Pinhole photography, in sharp contrast, almost always requires a tripod and a long exposure time. It’s a gradual process, a thoughtful and considered process. When a camera—any camera—is attached to a tripod, it ceases to be an immediate extension of photographer and becomes a device for accurately recording the thing the photographer has seen. Where the snapshot captures what the eye sees with little interference from the thought process, pinhole photography usually captures what the photographer thinks.

Zuili uses high speed black and white film to free the pinhole camera from the tripod. His LA photos are all hand-held. In a brief response to an online discussion about how he achieves the singular effect of his Fragments, Los Angeles series (from which all of the images presented here were selected), Zuili presented his approach as a simple equation: Ilford Delta 3200 + LA light = speed.

There is a strange and delightful consistency in all these contradictions—high speed film in a pinhole camera being used to shoot snapshots with a device designed for deliberate imagery, creating images that give modern life in a densely populated city an aura of a sparsely inhabited past, depicting a city that is itself a mass of contradictions. I don’t know…maybe ‘crazy’ is more accurate. But damn, it’s effective.

Zuili’s urban photographs—and particularly his images of Los Angeles—are a reminder of the unique properties of photography. All photographs—all of them—are, in effect, teleportation devices. They transport the viewer back through time, even if the journey is only to a few seconds in the past. They shift us across space; regardless of where you’re physically located when you see a photograph, you’re suddenly able to see someplace else—almost certainly someplace beyond your immediate vision. Photographs also convey us into the mind of another person—the photographer. They give us a glimpse of how that person sees and understands the world. We may not interpret what we see in the same way as the photographer but we are nonetheless seeing something that existed, however briefly, only in the photographer’s mind.

Gore Vidal famously said visiting Los Angeles is “like getting into a warm bath.” Having never been to LA, I’ve never quite understood that line. Now it’s beginning to make more sense. Guillaume Zuili’s Los Angeles may not be the ‘real’ LA, if such a thing exists. For those of you who live there, or who know the city well, it may not be your LA. But it’s a Los Angeles many of us will recognize down at the skeletal level, and while that may not make it real, it does make it true.