He wanted to be a painter. How many times have I written that about a photographer? Richard Billingham wanted to be a painter—an unlikely future for a poor boy growing up in a grimy council flat in an anonymous tower complex in a bleak neighborhood of the deeply polluted town of Cradley Heath in the West Midlands. He wanted to be a painter, but he had no money—his family was impoverished; neither parent held a job and his father was a hard-wired alcoholic. He wanted to be a painter, but when he applied for admission to art schools he was universally rejected—sixteen schools, sixteen rejection letters. He wanted to be a painter, but it didn’t happen. Instead, he became a photographer.

It’s really a most improbable story. Richard Billingham was born in 1970 to Ray and Elizabeth Billingham. Ray was a machinist, Elizabeth a housewife. When Richard was ten years old, Ray was laid off from his job. The family had to sell their home and move into public housing—what’s called ‘the projects’ in the U.S. and ‘council housing’ in Britain. At that point, Ray gave himself over completely to his alcoholism. Billingham told an interviewer that his father “…didn’t do much after that. He used to say ‘I’m just going to lie on my back and be dumb,’ and that’s what he did.” Ray apparently remained drunk or hungover for the rest of his life. Billingham’s mother—a large, heavily tattooed woman sometimes referred to as ‘Big Liz’—spent most of her time working jigsaw puzzles, chain-smoking, and amassing a collection of bric-a-brac. Billingham’s younger brother, Jason, was eleven years old when he was removed from the family (or, as the English so politely put it, he was ‘taken into care’). For a couple years Big Liz moved out of the apartment, leaving her teenaged son Richard in the care of her drunken husband.

It wasn’t the sort of family situation that would encourage a child to consider a career in the arts. A few reviewers have referred to the Billingham family as ‘underprivileged,’ which seems a remarkable understatement, not to mention a fairly narrow definition of the term ‘privilege.’ Billingham’s own description is more precise: he says the family was “…dirt poor. In the fridge there was no food; there’d be a block of fat and a loaf of bread.” There were cigarettes, of course, and always the cheap alcoholic cider and the home-brew that constituted the foundation of his father’s diet.

Billingham has said two things sustained him during those grim years. First, a book on British mammals, which he bought for thirty-seven pence. “I read it and read it again,” he said, “and got very interested in animals.” Billingham also discovered a talent for drawing—the primary art form of the poor, since all it requires is a pencil and a sheet of paper. He spent hours sketching cars, motorcycles, and, of course, animals from the book. He did well in school and at some point decided, despite all the life circumstances that stood in his way, to become an artist. To Billingham, that meant going to art school.

After being rejected by the first sixteen art schools (“It was really depressing to get rejected by the lot, but I was quite snobbish as a teenager and I’d applied to all the good art schools. I suppose I was pretty fussy.”) Billingham applied to—and was accepted by—the Bournville College of Art. There he studied painting and became quite taken with the work of Walter Sickert, the British Impressionist. Much of Sickert’s work involved moments of everyday life illuminated by soft light.

Like so many would-be artists, Billingham turned to his immediate family for models. With Big Liz gone from the family apartment and his brother in care of the state, only his father Ray was available as a prospective subject. Sickert’s work often featured models lying in bed; if it was good enough for Sickert, it was good enough for Billingham.

“It wasn’t too hard to get [Ray] to lie on the bed—that’s what he was doing most of the day. I’d do very quick paintings and he’d pose for about 15 or 20 minutes, but then he’d start to fidget or ask for a drink.”

That’s when Billingham turned to photography—not as a mode of expression, but simply as an aid to his painting. “I thought that if I could take photographs of him that would act as source material for these paintings and then I could make more detailed paintings later on.” He used the cheapest film he could find, much of it past its ‘sell-by’ date, and had the photographs processed cheaply at a nearby chemist/drug store.

At some point, however, Billingham’s attitude toward photography shifted. He began to see photography in a different light, so to speak. It’s not that surprising, if you think about it. Even if a photo is intended to be nothing more than the basis for a painting, the photographer still has to consider light and composition. The fundamental elements of art are essentially the same. Billingham stopped thinking of the photographs as source material for art and started thinking of them as art in and of themselves.

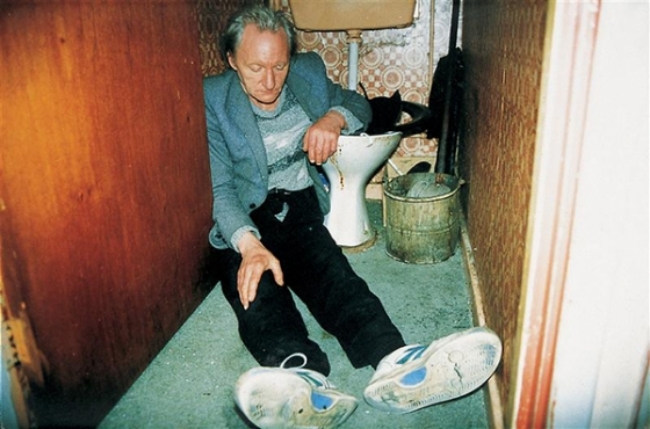

For six years, from 1990 to 1996, Billingham photographed his family. First, it was just his father Ray—drinking, sleeping, trying to decide if he could keep food down, drinking more, sleeping, laughing, drinking. Then, after his parents reunited, he photographed them both, along with the menagerie of cats and dogs she’d acquired in her absence. Later still his brother Jason returned to the family home, and also became a subject of the work.

And that, perhaps, is the most amazing thing about Billingham’s work. It’s not just who he photographed, it’s how unconcerned his subjects were by the act of being photographed. They knew—they had to know—they were being photographed; it just didn’t matter to them. They simply didn’t pay any attention to it. Part of that willful lack of concern, of course, was an aspect of Ray’s continuous state of intoxication; he simply didn’t care if Billingham took his photograph. Part of it was surely a result of habituation; he photographed his family with such regularity that they’d become oblivious to it and didn’t bother to alter their behavior in front of the camera. A less obvious reason the Billinghams paid no attention to the camera is that they didn’t think it was worth noticing. Photography—and, one suspects, art in general—simply didn’t merit their interest.

The six years during which Billingham photographed his family—the six years that changed him from a student of painting to a Fine Arts photographer—held other significant changes in his life. He transferred from the Bournville College of Art to the University of Sunderland. He obtained a degree in Fine Arts. And in 1995, he had his first exhibition of photographs. In the course of those six years, Billingham had actually become the artist he’d wanted to be.

The response to his first exhibition (at the Anthony Reynolds Gallery in London) was completely unexpected. One reviewer wrote: “Displayed in a line were scrungy photographs – poorly lit, blurry, oddly framed, made from crappy film stock … of scenes from a family life that cut through a century of posed studio portrait groups.” Nobody had seen anything quite like his photographs. The same reviewer later wrote: “Billingham’s images didn’t just evolve the genre; they smashed their way through to another kind of vérité encounter.”

The exhibit, called Ray’s a Laugh, was an immediate success—both critically and financially. The following year the photographs were published as a book with the same name. In 1997 his work was featured in the Sensations exhibition at the Royal Academy in London—a show that’s come to be seen as one of the great cultural moments in modern art.

Ray and Big Liz were presumably proud of their son’s success, but apparently weren’t terribly interested in the book or the photographs. After all, it was just a bunch of snapshots of themselves; surely anybody could do it. Said Billingham, “They relate to the work, but I don’t think they recognize the media interest in it, or the importance. I don’t think that they think anything of it, really.” Their lack of interest is sadly understandable; poor and working class folks are indoctrinated to think of art—or almost any form of high culture—as something outside of their existence, something they can’t really comprehend, and a waste of their time. Art, for a lot of people, is something to be hung above the sofa, preferably something that complements the furniture.

Billingham’s family photographs sparked a testy debate in the arts community. Some saw the series as political commentary—a critique of the Conservative government that had held power for more than a decade, and their policies toward the poor and working class. Some saw the photos as exploitative and voyeuristic, a sort artistic adaptation of the Jerry Springer-ization of modern television culture. Some saw the work as an expression of proletarian rage and resentment, which manifested itself either externally through mindless violence (football hooliganism, racist thuggery, domestic aggression, etc.) or internally through self-destructive behavior (alcoholism, drug abuse, etc.). Other critics simply saw the photographs purely in terms of the aesthetic and how they fit into existing modes of artistic expression. One critic remarked that Ray’s a Laugh “belongs to a rhetorical and ritualized system of the family photography while it simultaneously contradicts the system by its lack of poses.” One wonders what Ray and Big Liz would have made of that.

Few, if any, of the critics engaged in the debate had any real familiarity with council housing or desperate poverty or the unremitting, persistent boredom that’s an inevitable by-product of chronic unemployment. Certainly, addiction and boredom aren’t the exclusive province of the poor; rich folks and middle class people also experience those issues—they just experience them in more comfort, with cleaner clothes and better vegetables.

Billingham, it seems, hasn’t bothered to become involved in the debate.

“I soon realized that people liked the family pictures for reasons that I never intended. They just like to look at my mum’s tattoos or the stains on the wallpaper or the dirty floor.”

Billingham himself has moved on to other projects. He spent some time working in hi-8 video. He began another series of still photographs based in the Black Country—a section of the British Midlands that’s one of the most heavily polluted environments in the Western world; a network of coal mines and coking operations, coal-powered iron mills and steel founderies, and other coal-based industries (it includes Cradley Heath, Billingham’s hometown). He has become a lecturer in Fine Arts Photography at the University of Gloucestershire. His most recent series of photographs and videos is, happily, about zoos—a project for which he spent two years traveling and visiting the world’s best zoological gardens. He finally got to see all those animals he’d first seen in that book he’d bought.

Ray and Big Liz have both since died.

“Ray got moved into an old people’s home up the road. At first, Liz would go and see him once a day, then it was once a week, then once a month, then months went by. She died about three years after that. Of a blood clot, at 56. And then he died the year after. He was 74. Not much of a story really.”

Not much of a story, really. A story that’s so sadly common in poor neighborhoods that it doesn’t merit much more than a sentence or two in a little-noticed blog about photographers. It would be tragic, except that tragedy requires an audience to be appreciated. The audience is busy looking at the photos.

I rather doubt Richard Billingham still has that book of British mammals he bought as a child. Even so, I suspect it’s the best thirty-seven pence he’s ever spent.