There are photographers whose work is so influential in scope, in style, and in approach that to attempt to write anything about them is intimidating in the extreme. For me, Robert Frank is one of those photographers. His work not only changed the way modern photography is approached, it changed the way modern photography is experienced. That’s a bold claim, of course, but it’s a claim very few people familiar with the history of photography would dispute.

For two years in the middle 1950s, Frank—a Swiss immigrant—traveled the United States creating a very personal and incisive photographic documentary of his journey. The culmination of that odyssey was a book, The Americans, that half a century later remains one of the most significant contributions to American photography—indeed, to all American art. It’s a most improbable book with an improbable genesis and an equally improbable aftermath.

In this salon, I’m going to concentrate on The Americans; the next salon will examine Frank’s life before and after its publication.

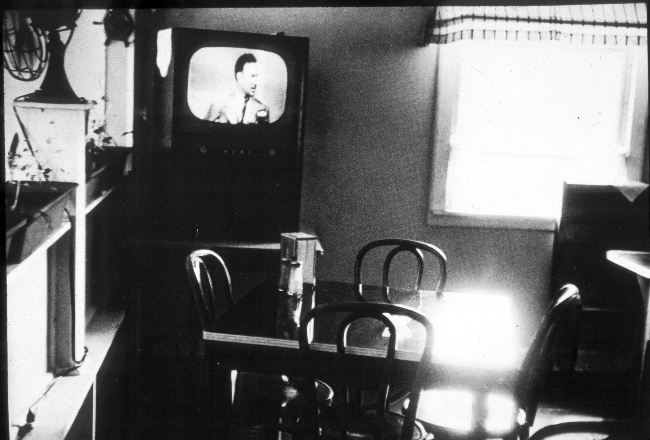

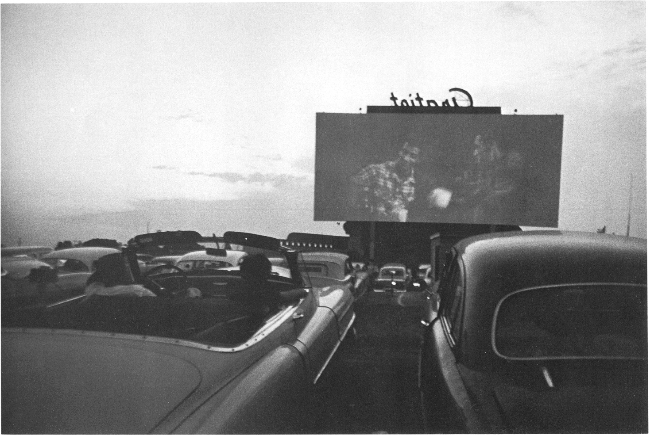

This is really a story of an era as much as it is a story about a photographer and his odyssey. The United States in the 1950s presented two obvious public faces to the world. There was the face of prosperity—America as the Land of Opportunity, a beacon of freedom, a nation of progress and contentment. This was the America of Leave It To Beaver and I Love Lucy, a nation in which housewives ran the Hoover while wearing pearls and a dress. Consumerism was seen as a virtue; everybody wanted to be the first on their block to own a new television, a new car, a new washing machine. This was the America of innovation and innocent amusement, the America that was capable of inventing of the hula hoop and constructing a vast interstate highway system.

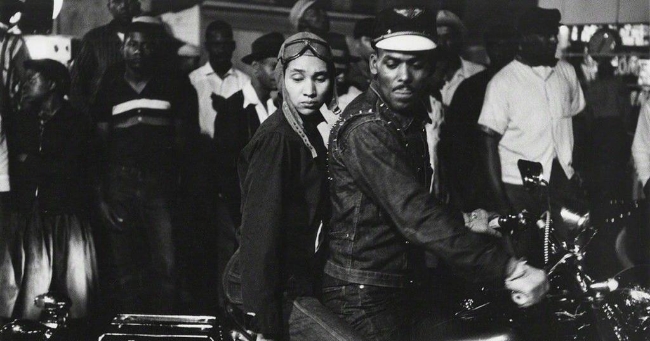

There was also the face of unease, however, and anxiety. The 1950s was the era of the Cold War and the Space Race. This was the America in which nuclear fallout shelters were constructed in public buildings and schools, the America of the backyard bomb shelter. The McCarthy hearings looked into ‘un-American activities’ and Hollywood began to blacklist actors, writers and directors whose politics didn’t follow the orthodoxy. Racial segregation and discrimination was not only common, but legal, and the division between economic social classes was beginning to become more distinct.

Robert Frank, who’d come to the United States in 1947 filled with optimism and faith in America, felt something was happening to—or within—America. He applied for a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, an audacious request for money that would allow him to travel the U.S. and create “a visual study of a civilization.” He forthrightly informed the Guggenheim that his wouldn’t “be a carefully planned trip, but a spontaneous record of a man seeing this country for the first time.” He wrote the project would be “one that will shape itself as it proceeds, and is essentially elastic.” In other words, he asked the Guggenheim to give him a large sum of money and turn him loose on the road without any restrictions, without any detailed accounting, and without any schedule.

And they gave it to him. Twice.

In May of 1955 Frank—31 years old, married with two young children—bought a second-hand car with his grant money and set out on the first of several trips into America. Sometimes he brought his family, sometimes he traveled alone. His only constant companions were his Leica cameras. He went into the Deep South, into the Midwest, into Texas and cowboy country, into the Big Sky country of Montana, into California and the Pacific Northwest. He went everywhere, and everywhere he went he shot photographs.

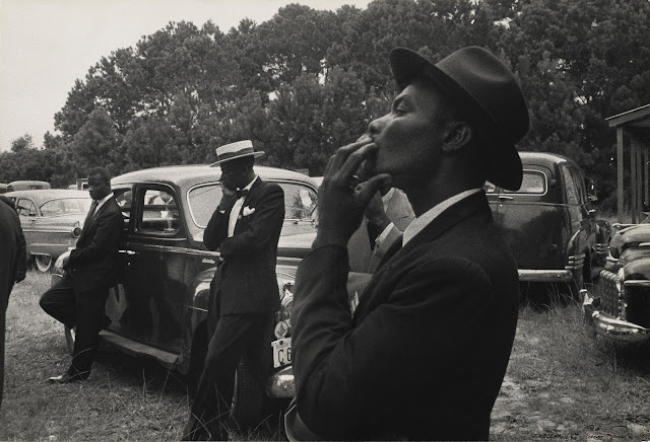

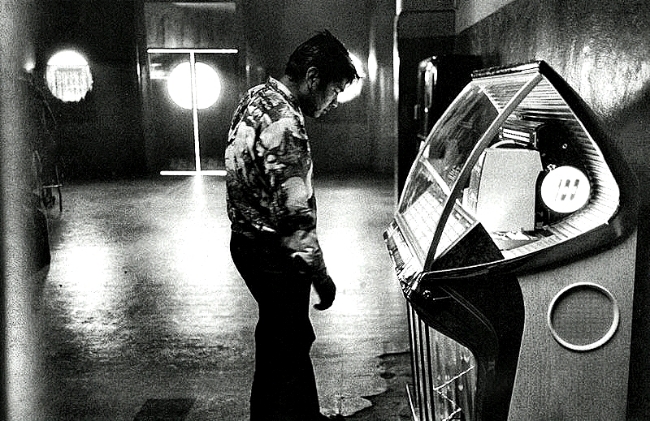

Although his destinations were often determined by intuition, Frank didn’t shoot randomly. In his Guggenheim application he’d outlined some of the visual tropes he expected to explore: flags, cars, diners, jukeboxes—things he considered to be quintessentially American. During his travels, though, Frank discovered other recurring themes he believed were coming to represent America: religiosity, racism, conspicuous consumption, as well as a sort of blustery patriotism and jingoistic boosterism.

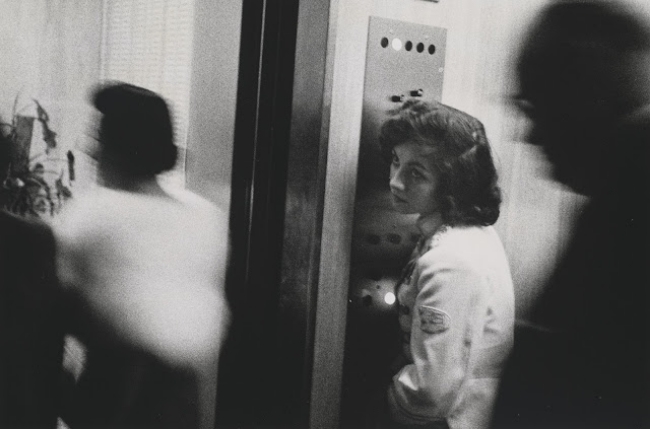

He periodically encountered hostility on the road. I suspect some of that was a result of his approach. Frank, according to his friends, generally kept his Leica hidden away under his jacket or in a pocket until he saw something to photograph. He’d then quickly raise the camera to his eye—or shoot from the hip—often using only one hand. Since he tried not to be noticed, and rarely spoke to his subjects, it’s not surprising some people found his behavior annoying or suspicious.

On the other hand, speaking to people didn’t always serve him well. In Arkansas, for example, he was pulled over by a Little Rock police officer who was suspicious of a car bearing New York license plates, driven by a disheveled-looking man. The officer’s suspicions were increased when he heard Frank’s strong foreign accent. He then discovered Frank’s driver’s license didn’t match the name on the vehicle registration (an oversight from having recently bought the car with the Guggenheim money). A search of the car revealed the camera equipment and maps with locations and routes marked in red. The officer wasn’t reassured by the letter from the Guggenheim Foundation (which he’d never heard of and which sounded foreign and Jewish) nor by Frank’s explanation that he was being paid to drive around the nation and shoot photographs. Frank was arrested and spent three days in jail before the matter was cleared up.

Frank’s one-year Guggenheim grant was renewed for a second year. At the end of those two years, he’d accumulated a massive stock of images—627 rolls of film, nearly 25,000 negatives. What came next was, as Frank described it, “the biggest job…the selection and elimination of prints.” It took a few months to reduce the number of images to a thousand, and another couple to cull those down to a mere eighty-three photographs to be included in the book. And when he was done—after all that time on the road and all that time studying his contact sheets and harvesting images—he discovered that no U.S. publisher would touch it.

In the heart of the 1950s, publishers of photography books knew what they wanted, and it wasn’t Robert Frank. They wanted an idealized America—an iconic America, clean and crisp and in focus, a proud and majestic Ansel Adams America. They wanted images of Americans to reflect that attitude as well—happy, prosperous Americans, confident and patriotic. They wanted the same America they’d seen in other photographic books. They most certainly did not want an America full of racial anxiety, disrupted by tension between economic and social classes, an uneasy and alienated America, a consumption-oriented America increasingly obsessed by commercialism, a nation out of balance and off-kilter. They didn’t want Robert Frank’s America.

In order to find a publisher for his book on America, Frank had to go to Europe. In 1958, French publisher Robert Delpire released the first copies of Les Americains. That was apparently enough to convince Grove Press in the U.S. to reconsider. Their decision to publish an English edition was made easier by the fact that Beat writer Jack Kerouac (who Frank met at a party in New York City) had agreed to write about the photographs.

“That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured….with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film…. To Robert Frank I now give this message: You got eyes.”

You got eyes—and Kerouac was absolutely right. Frank’s photographs were often sad and were distinctly poetic—and poetic in unexpected but very deliberate ways. It’s difficult now to fully appreciate the impact of The Americans on the American photography establishment of the 1950s. They called the photos “badly framed” and “willfully obscure.” Some said they were “unpatriotic.” Popular Photography magazine panned The Americans, disparaging the photographs because of their “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness.”

Nobody was shooting photographs quite like this. Henri Cartier-Bresson, of course, was already making startling images; in the U.S. Garry Winogrand was working the streets of New York City following in Cartier-Bresson’s footsteps—but Frank’s work was noticeably different. Photographers who’d learned to appreciate the approach of Cartier-Bresson complained that Frank’s photographs didn’t seem to be about the “decisive moment.” And they were right. Frank didn’t believe in decisive moments; he didn’t believe there was an instant in which some sort of Truth could be revealed through “the perfect combination of form, gesture and expression.” In fact, he rejected the entire concept of photography as a universal language “understood by all—even children.”

And therein lies the key to The Americans. Frank wasn’t trying to create a set of easily comprehensible individual images that depicted specific moments, decisive or not; he was creating a series of images meant to be taken as a whole, in a logical sequence. He was, as Kerouac suggested, creating a visual poem. Like a poem, the structure—the sequence of words or images—is as critical as the words and images themselves. You can no more understand The Americans by looking at individual images (as shown here) than you can understand a poem by looking at individual words. Just as a complex poem must be read several times before it’s completely understood, The Americans has to be viewed more than once to fully appreciate.

For example, the book begins with a photo of a parade in Hoboken, New Jersey—a flag draped from a working class apartment, partially obscuring the people inside. The next photo—men in suits and top hats on a parade stand, a flag neatly pinned in the background. Frank doesn’t actually ask the questions; he leaves it to the viewer to figure them out. Who is the parade really for? Who is the flag really for? And so it goes, page after page and photo after photo, clues and hints, symbols to be interpreted and themes to be deciphered.

Frank’s early critics were, in many ways, correct. The photographs in The Americans are often badly framed and willfully obscure. The horizon lines are, in fact, drunken and the exposures are sometimes muddy. That’s appropriate, because Frank’s photos are so often of the things and people we see in our peripheral vision, out the side of our eye, while looking at other stuff. If his photographs are tentative and imperfect, it’s because America in the 1950s was tentative and imperfect, and because most of us go through life that way.

With The Americans, Robert Frank introduced something new to photography—a sort of Beat philosophy, grounded in contradiction. His work was open and visceral, gritty and spontaneous. And yet it’s also done with deliberation and reveals a definite spiritual yearning. Frank may exhibit a weary cynicism, but it’s cynicism born out of disappointed hope. The key term there is hope, because without hope there is no disappointment.

Half a century after its publication, we’re still hopeful and still disappointed, and we’re still struggling to fully understand The Americans. But this is still true: Robert Frank, you got eyes.