I’m often amazed at how large some lives are. The life of Roman Vishniac was large enough for three or four people. Yet, outside a fairly small circle of scientists, historians, and scholars specializing in Jewish history, the name of Roman Vishniac is largely unknown.

He was born in 1897 in the dacha of his grandparents, which was located in the town of Pavlovsk, just outside of St. Petersburg in Russia. His father owned a company that made umbrellas; his mother was the daughter of diamond merchants. Their wealth gave young Roman opportunities unavailable to most; for example, at age seven he had both a microscope and a camera. He used them together to create microphotographs of the sorts of things that fascinate children, things like the legs of a cricket or pollen spores.

His family’s wealth also allowed the Vishniacs to live in Moscow, from which almost all Jews had been expelled only a few years earlier. It allowed him to attend universities in Moscow, which limited Jews to only 3% of the student population. There, Vishniac was able to obtain a doctorate in zoology, a doctorate in Oriental art, and a medical degree. Of course, as a Jew in Russia meant Vishniac couldn’t actually use those degrees. Jews were prohibited from practicing many professions.

In 1918 Vishniac’s parents, weary of the blatant discrimination in Russia (which had increased after the Russian Revolution), moved to Berlin. At that time, Berlin was considerably more friendly to Jews; in retrospect, of course, the move wasn’t a wise idea. Vishniac remained in Moscow for two more years to finish his education, then re-joined his family in Berlin.

Throughout this period, Vishniac continued to practice his photography, though his interest remained primarily in microscopic subjects. That changed in 1935 when he was commissioned by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee to document life in the shtetlekh of Eastern Europe. The photos were to be used as part of a fund-raising effort (the AJJDC offered a variety of programs to support Russian and Eastern European Jewry).

Coming from a rather wealthy and privileged family, this experience shocked Vishniac. He discovered, for example, that there were places where Jews weren’t allowed to own cameras. In other places, Jews were only allowed to buy two rolls of film at a time. Nor did the people who lived in the shtetls always welcome him and his cameras. Not only was Vishniac an outsider from an obviously different social class, his photography was considered by many to violate the Torah’s prohibition against graven images.

After completing his commission for AJJDC, Vishniac decide to continue the project on his own. It seemed to him that the political and social climate of Eastern Europe meant the probable extinction of the shtetl culture and way of life that had existed for centuries. Decades later Vishniac said,

“I felt it was my duty to my ancestors to preserve a world that might cease to exist. I wanted to save the faces. I especially wanted to take pictures of children, since Hitler eventually killed more children than old people. He wanted to destroy the young.”

For the next four years—1935 to 1939—Vishniac traveled through the shtetlekh of Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Hungary and Romania. Persecution of Jews increased each year. Vishniac learned to disguise himself as a traveling fabric salesman to escape the attention of local authorities. He began to shoot many of his photographs surreptitiously—particularly those shot outside in the daytime—to avoid the harassment of the local police and the resistance of the more Orthodox Jews. He hid a Rollieflex beneath his coat for those outside photographs. Vishniac also carried a concealed Leica, hidden in a scarf wrapped around his neck. He used the Leica primarily for low-light situations, including portraits shot inside. He learned to pack a kerosene lantern to use as a light source for those interior portraits.

Despite his precautions, Vishniac was detained eleven times during those four years. Each time he managed to free himself without much trouble. In 1938, he actually sneaked into a German internment camp in Zbayszyn where Jews were held awaiting their deportation to camps in Poland. It took him two days to find a way to escape. The photos of the camp were sent to the United Nations, which was reluctant to accept the reality of such camps.

Vishniac’s parents and his wife and children eventually fled Berlin. His parents moved to the south of France (where his mother died of cancer and his father remained hidden throughout the coming war); his wife and children went to Sweden, where her parents then lived. Vishniac himself, though, continued to use Berlin as his home base from which he’d make his journeys to the rapidly dying shtetlekh. In 1940, however, he was arrested and detained for the last time. The arrest took place in Paris, and Vishniac spent three months in a French deportation camp. His wife, aided by the AJJDC (which had commissioned Vishniac’s first foray into the Eastern European villages), eventually manage to get him released and provided him with a visa to travel to Lisbon in Portugal. From there he escaped to the United States.

Between 1935 and 1940 Vishniac shot approximately 16,000 images of shtetl life and culture. Sadly, he only managed to retain a couple thousand negatives when he made his way to the U.S. But those images provide the most historically accurate and significant photographic documentation of the world of the shtetl—a culture that, as so many people feared and predicted—has essentially been extinguished.

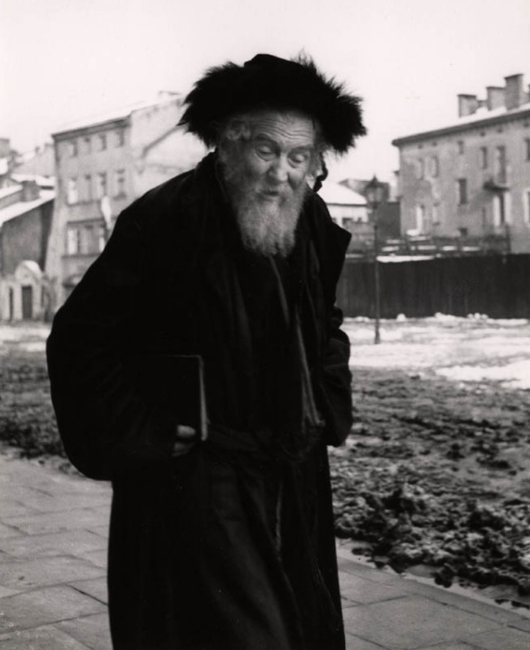

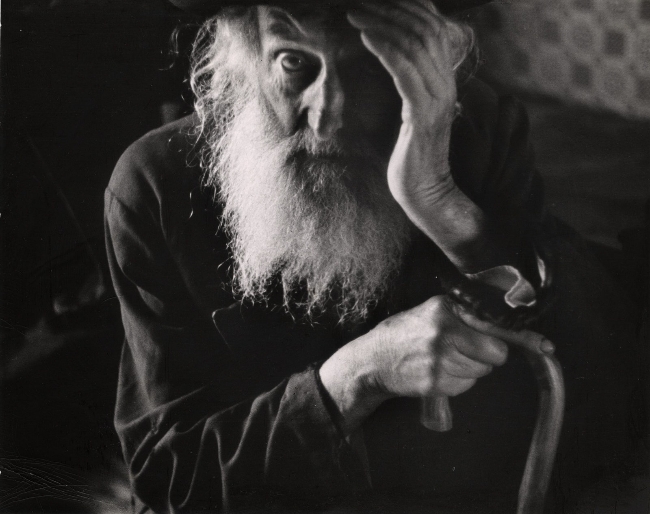

It needs to be understood that the shtetl was, in effect, an isolated world. The inhabitants—Ashkenazi Jews—spoke Yiddish and wrote in Hebrew, regardless of the native language of the surrounding country. Their customs were largely unchanged for several hundred years. Almost everybody, regardless of occupation or social status, was something of a Torah scholar. It was a world in which the cobbler was also a poet, the fishmonger was a philosopher, the drayman was a numerologist. Any conversation was potentially a theological discussion or debate. Every conversation was accompanied by a series of gestures and shrugs and half-sentences that carried meaning, the significance of which was lost to outsiders. The young boy with the toothache pictured above was a scholar-in-making (note his much-tattered book) and had he been born half a century earlier would likely have turned into the village elder we also see above.

The insulated culture of the shtetl made it easier for anti-Semites to paint them as aliens, as ‘the other,’ as non-citizens, which in turn made it easier to persecute them. And each persecution made the shtetl that much more insular and unwilling to deal with outsiders. It was a unique social world that took centuries to create–but only a decade or so to destroy.

After arriving in New York City in 1940, Vishniac had difficulty finding employment. He made some money shooting portraits, mostly of fellow immigrants. The next year he visited Albert Einstein, partly on the pretense of giving the regards of mutual acquaintances in Europe. During the visit Einstein became distracted while pondering some physics question. “He disappeared, moved into a higher sphere,” Vishniac said. “He was completely oblivious to my camera.” So he shot the great physicist’s portrait while he had the opportunity, the portrait Einstein would declare his favorite.

But there was little money or certainty in portrait photography, so Vishniac returned to his first love—photomicroscopy. He became an expert in photographing live insects, which was singularly difficult to do. Reportedly, Vishniac would rub the local flora over his body and lie in the grass for an hour before beginning to hunt insects, in order to disguise his scent. He practiced holding his breath for minutes so that he’d be able to make long exposures without disturbing the camera (photographing insects in the wild makes the use of a tripod problematic). Vishniac became well-known in the world of scientific photography.

But he will always be best known for his images of the shtetlekh. In 1983, two hundred of the photographs Vishniac shot between 1935 and 1939 were published as a book entitled A Vanished World. The tragic fact that so many of the people appearing in those photographs—children and adults alike—almost certainly were the victims of industrial murder makes the photographs all the more haunting. Those photos, taken under the most trying conditions, are so suffused with emotion—with compassion—that they make viewers almost hold their breath.

That world may have vanished, along with the people who lived in it, but through Roman Vishniac’s photographs, their ghosts will linger and remind us that such a unique culture once existed.