He may have murdered his father. That statement seems an odd way to start a discussion about one of the most celebrated portrait photographers of his era. Certainly, it’s an issue that rarely gets mentioned in any of the articles written about Philippe Halsman. There’s a very good reason for that: it rarely gets mentioned because it has no bearing on his photography. On the other hand, it’s a fact that shaped Halsman’s life in a number of ways.

Halsman was born in Riga, Latvia in 1906. His father was a dentist, his mother a principal of a grammar school. There doesn’t appear to be anything extraordinary about Halsman’s young life—he went to school, did well, studied electrical engineering at a university in Dresden. In 1928, during a break in his studies, Halsman went on a hiking tour of the Austrian Alps with his father, Morduch Halsman. At some point during that hike, according to Halsman, he heard a shout and turned to see his father falling down the side of the mountain and into a river below. He clambered down the mountainside, pulled his father from the river, and went for help, which came in the form of a peasant woman and a nearby shepherd.

The police arrived, recovered Murdoch’s body, and questioned Halsman several times. His account of the event changed somewhat with each interview and was inconsistent with evidence found at the scene—a rock with Murdoch’s blood and hair had been recovered, and the evidence suggested it had been used to strike Murdoch several times. In addition, Halsman’s behavior at the scene, at the alpine inn where he was first questioned, and still later in Innsbruck where he was confined, was seen as suspicious. If that wasn’t enough, Halsman had the misfortune of being Jewish in Austria at a time when anti-Semitism was on the rise.

He was arrested, put on trial for murder, found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. The murder trial had attracted a great deal of attention in Europe, and the verdict was quickly challenged by journalists, by legal scholars, and by eminent intellectuals (including such figures as Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein. His family in Latvia believed him to be innocent. The Austrian Supreme Court reversed the conviction and ordered a new trial. The second trial, in 1929, also resulted in a guilty verdict, but of the lesser offense of manslaughter. Halsman was sentenced to four years of imprisonment.

The second verdict was also condemned by intellectuals. In 1931, Halsman received a presidential pardon. He was also ordered to leave Austria and never to return.

Why is this incident important to our discussion of Halsman as a photographer? For reasons that will soon become more clear.

After he left Austria, Halsman moved to Paris. There, with the help of his family, he began to study photography—a craft he’d always found interesting. He shot portraits primarily, and soon began to submit his work to fashion magazines. The prevalent style in fashion photography in the 1930s were dreamy, soft focus inages. Halsman gave them sharply focused, dark, dramatic photographs that often included odd and unusual props. The French fashion magazines loved them. He quickly developed a reputation and became a popular fashion and portrait photographer.

With a burgeoning career as a successful photographer, Halsman married and soon became a father. Life would have been grand, except for the roiling political situation in Germany and Austria. In 1940, that situation boiled over; the German Army invaded France. Halsman’s wife and daughter, being French citizens with French passports, were able to flee to the United States. As a Latvian citizen, Halsman was unable to get an exit visa. He fled to Marseilles, where others sought a way out of the country. Once again Albert Einstein intervened, and persuaded the government to issue Halsman a passport and an exit visa.

If Halsman had not been accused of murdering his father, it’s unlikely he’d have moved to Paris and become a photographer. Nor would he have come to Einstein’s attention. Had he not gained Einstein’s attention, it’s unlikely he’d have obtained a passport and visa to travel to the U.S. If he hadn’t come to the U.S. he’d have never met a young model named Connie Ford, who agreed to pose for Halsman in exchange for prints for her portfolio.

He photographed Connie Ford in front of an American Flag, which caught the attention of publicists at Elizabeth Arden, who was releasing a new line of lipstick called ‘Victory Red’ in support of the troops fighting in World War II. That photo was enough to get Halsman a chance to shoot a new hat design for Life magazine, a photograph that was so good the editors put it on the cover. It was the first of Halsman’s 101 cover images for Life. None of which would have happened if Halsman hadn’t been accused of murdering his father.

It’s difficult now to appreciate how influential Life magazine was in 1942, when Halsman first made the cover. The concept of photojournalism itself was fairly new. Before the inception of news magazines, most people obtained their information about the world through newspapers, the radio, and newsreels shown at movie theaters. News magazines like Life offered a new way to look at and understand news. They not only covered hard news stories at the national level, they also covered international news, celebrity news, science, fashion, politics, travel to exotic locations. They did everything; they were, in effect, all the channels on cable and satellite television today. By appearing in the pages of Life Halsman’s photography reached a massive audience. Being on the cover garnered even more fame.

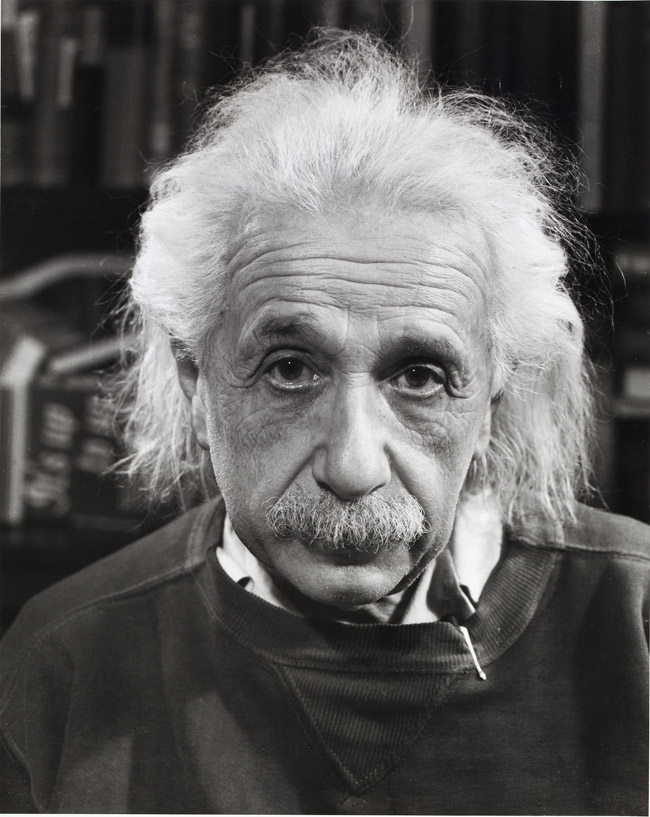

Halsman soon became one of the pre-eminent portrait photographers. He photographed everybody—politicians, celebrities, musicians, comedians, scientists—and many of those photographs became iconic images. Among those is the 1947 photograph of the man who’d been so influential in his life, Albert Einstein. During that photo session the physicist began talking about his regret at playing an important part of developing the atomic bomb, which accounts for the somber expression on his face.

A few years later Halsman was commissioned by NBC television to shoot a series of portraits of famous comedians—Groucho Marx, Milton Berle, Red Skelton, Bob Hope, and the musical-comedy team of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. During those shoots he noticed that many of the comedians jumped spontaneously during their acts. He began asking them to jump for his photographs. Not long after that, Halsman began asking almost all of his subjects, at the very end of their portrait session, to allow him to photograph them jumping.

This soon became something of a Halsman trademark. He even developed a rather tongue-in-cheek philosophy he called Jumpology. “When you ask a person to jump,” he said, “his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls so that the real person appears.” Very few people refused to jump for Halsman—Herbert Hoover refused, as did Edward R. Murrow and pianist Van Cliburn. As Halsman’s ‘Jump’ photos gained attention, even the most staid and reserved subjects readily agreed. Vice President Richard Nixon jumped with his suitcoat still buttoned, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor removed their shoes and jumped, the president of Ford Motor Company and his wife and children all jumped, Robert Oppenheimer—the father of the atomic bomb—jumped and tried to touch the ceiling.

For the most part, all the images in the Jump series were shot in a period of six years. They were almost always the final shots of a portrait shoot. It’s easy to imagine Halsman’s subjects sitting for their portrait, always waiting—either eager or afraid—for the invitation to jump. In a very real way, the Jump photographs are subversive. They undermine what traditional portraiture does. For some the act of jumping must have been liberating. For others, the act was surely a task—a chore during which they had to control themselves while appearing uncontrolled.

One of the picture editors at Life referred to Halsman’s Jump series as “a kind of Rorschach test, for the sitters and for himself.” That sounds both absurd and absolutely correct. What can we tell about Audrey Hepburn in mid-jump? She’s clearly aware of the camera, and yet there’s a certain spontaneity in her pose and laugh. What can we tell about Eva Marie Saint and her dramatic dancer’s leap? She looks as if she’s being drawn up out of the city and into the clouds by some spiritual force. Can we really tell anything about these people? It feels as if we should.

Not all of the Jump photographs were spontaneous. Perhaps the most famous of them was carefully composed and meticulously rehearsed. Halsman had become friends with the surrealist painter Salvador Dali, and they collaborated on a number of projects together, including a small book entitled Dali’s Mustache, comprised of thirty-six photographs of the painter’s famous (or infamous) mustache. For Dali’s Jump photograph, the two of them—with the help of several assistants—created a surrealist composition.

They suspended a small step-ladder and two easels—each with one of Dali’s paintings on it—from the ceiling of Halsman’s studio. Halsman’s wife, off-camera, held a chair in the air. On the count of three, one assistant threw a bucket of water in the air, three other assistants each threw a cat in the air, and on the count of four Dali himself leapt up, and Halsman released the shutter of his camera. While the assistants tidied up the mess and corralled the cats, Halsman hurried to the darkroom and processed the 4×5 negative. They repeated that scenario 28 times over a period of more than six hours before Halsman and Dali were satisfied with the shot. The photograph was titled Dali Atomicus, an homage to one of the paintings in the photo (Leda Atomica).

Halsman once said “A true portrait should, today and a hundred years from today, be the testimony of how this person looked and what kind of human being he was.” That seems a tall order; I don’t quite believe it, and I’m not convinced even Halsman fully believed it. But the statement says something about the man and I’m completely convinced he attempted to create images that revealed something true and fundamental about his subjects.

Halsman also said this:

“Every face I see seems to hide and sometimes, fleetingly, to reveal the mystery of another human being…. Capturing this revelation has become the goal and passion of my life.”

That is a statement I can believe without reservation. Portraiture is perhaps the most difficult photographic field, simply because it asks so much of the photographer. Portraiture asks the photographer to reveal something the subject may not want to reveal, perhaps something of which the subject may not even be aware. It is an impossibly demanding field. Philippe Halsman, I suspect, came as close as anybody could to meeting those demands.