GRAPHIC IMAGES — GRAPHIC IMAGES — GRAPHIC IMAGES

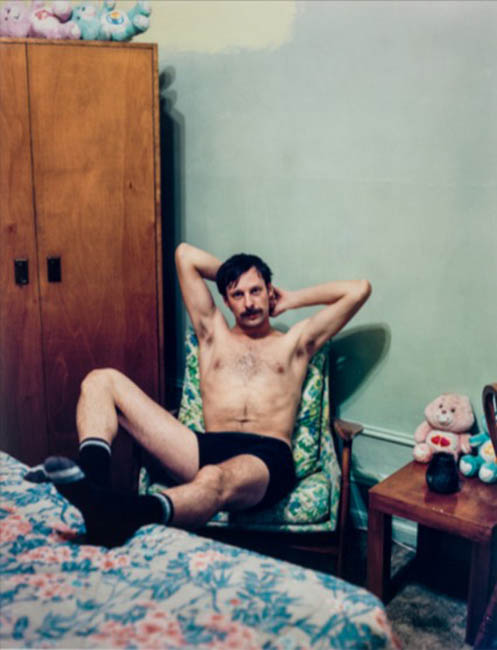

I confess—I don’t quite know what to make of Leigh Ledare and his work. His most recent project—a series of black and white photographs of a Russian motorcycle gang, the Night Wolves—is pretty straightforward; it falls neatly into the category of social documentary photography. Prior to that, Ledare did a series of photos that grew out of a rather intriguing idea: he answered the personal ads of older women looking for companionship/love/sex and paid them to photograph him in a situation of their own choosing. That series (Personal Commissions) isn’t quite as easily categorized. It’s clearly grounded in the documentary approach, though the concept is decidedly novel. Ledare describes these images as “indirect portraits of the women who photographed him.”

Neither of those series received a great deal of critical attention. I suspect that’s true in part because the project that brought Ledare to the attention of the art world—the project he’s best known for and for which he’ll be remembered. That project is anything but straightforward or uncomplicated.

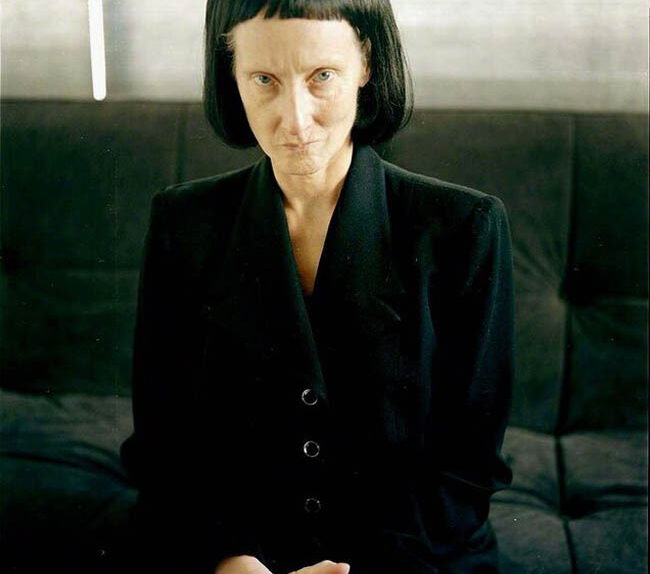

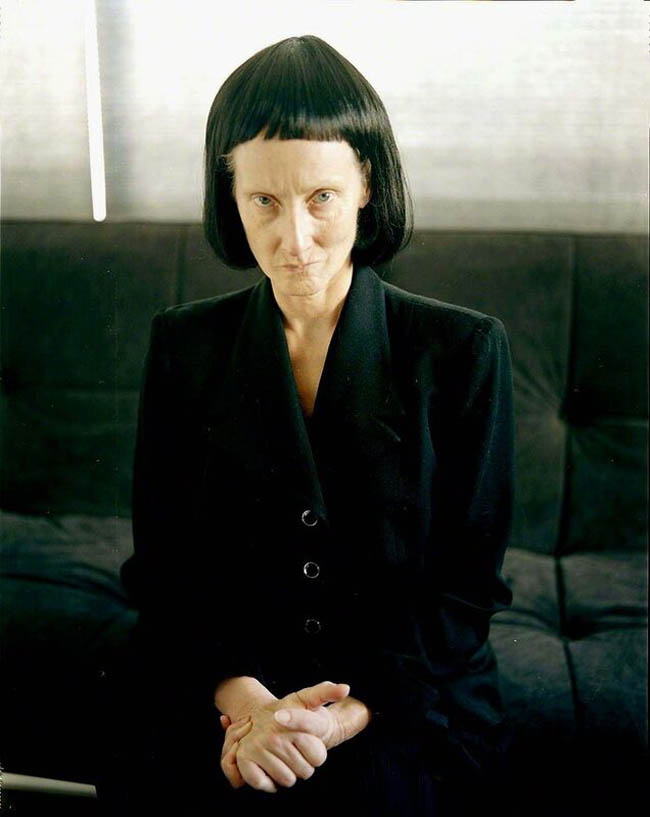

The series (the exhibition was called You Are Nothing to Me. You Are Like Air; the book was entitled Pretend You’re Actually Alive) is comprised of photographs of Ledare’s mother. There’s certainly a documentary quality to the series—but what’s actually being documented is open to question.

In Pretend You’re Actually Alive Ledare’s photographs of his mother range from the tender to the provocative, from the formal to the pornographic. They’re clearly a collaborative effort; Ledare’s mother, Tina Peterson, is very obviously engaged in the process. There is some indication that she, in fact, proposed the idea for the project to her son. The question, then, is this: do the photos in Pretend You’re Actually Alive depict a person or a persona? There’s no doubt that there’s an element of fiction involved in the project, but it’s not at all clear whether that fiction is an integral part of Tina Peterson’s personality. Is there a difference between the person and the persona?

And if that’s not complex enough, there’s always the other question—the question that everybody asks: just what in the hell is Leigh Ledare doing taking pictures of his mother giving blow jobs and having sex?

Tina Peterson first garnered some public attention in 1965 when she was 16 years old, part of a feature on aspiring ballerinas published in Seventeen magazine. She later danced with the Joffrey Ballet and the New York City Ballet. She apparently worked briefly as a model. At some point she married and had two children (Leigh was born in 1976). The marriage failed. Tina Peterson’s ballet career turned into gigs as an exotic dancer. Leigh left home at age fifteen.

Despite that, his life doesn’t sound particularly grim. For a while Leigh Peterson (it’s unclear when he changed his surname to Ledare) was a fairly prominent part of the West Coast skateboarding scene. He appeared in a few skateboarding videos. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design and earned a BFA in 2000. He worked for a while as an assistant for Larry Clark (a famed photographer and the director of the controversial movie KIDS). He eventually earned his MFA from Columbia University.

At some point around the time he finished his BFA, Ledare returned to his mother’s home for a Christmas visit. He hadn’t visited her for at least a year. Ledare described the scene in an interview:

“I knocked on the door. A few minutes later the door opened and she was standing there naked, smiling at me with her hands on her hips. She asked me to follow her to her room while she got dressed. As we moved down the hallway to her room she began speaking to someone. On her bed, a young man, almost exactly my age, was sprawled out naked. He rolled over to see me, saying hello, before rolling back over on his side and returning to sleep. I saw this as her way of announcing to me what she was up to at this period in her life, almost as though to say take it or leave it.”

We’ve seen other photographers explore their personal lives, of course. In the 1980s Nan Goldin began photographing the stark reality of her life and the lives of her friends—the drugs, the sex, the brutality. A decade later, Richard Billingham started a study of life with his alcoholic father. About the time Ledare began his project, we saw the golden child Ryan McGinley turn real life documentation into performative theater for the camera, deliberately blurring (and let’s face it, often completely erasing) the line between life and stage.

What Ledare has done is rather different. He has, in a way, combined the best and the worst elements of Goldin, Billingham, and McGinley. Like McGinley, Ledare’s photographs of his mother are as much about performance as they are about her life. Even if the performance is compelling, the subject is necessarily depersonalized; the performance matters more than the performer.

Like Billingham, Ledare is exposing a dysfunctional family—but where Billingham always manages to include tenderness and affection even in the most uncompromisingly disturbing images, there is something almost clinical in Ledare’s approach. Like Goldin, Ledare doesn’t turn away from circumstances that can only be described as depressing and degrading. But Goldin’s work is grounded in reality where Ledare’s grows out of a presentation the subject wants to present as reality, or perhaps wants to believe is reality.

It’s not surprising that many—probably most—of the reviews of Ledare’s Pretend You Are Alive include some blather about the Oedipal Complex (Sigmund Freud’s theory that children harbor an unconscious or repressed desire to sexually possess the parent of the opposite sex). It’s an easy way for an art critic to fill up a paragraph or two, and at the same time hint that Ledare’s relationship with his mother is sexual, without having to actually say that. But it’s hard for me to take that seriously—not just because of the outdated Freudian notions, but because the idea doesn’t seem relevant.

It seems to me that at some point in the project Ledare ceased to see Tina Peterson as his mother and saw her primarily as a subject/performer. Ledare claims the camera gives him the emotional distance necessary to record the scenes in front of him. He’s also said it “serves as a catalyst to sort of push the relationship.” Since Ledare is a participant in this behavior, I don’t think we can, or should, rely on him to be objective or entirely honest about his role. But at the same time, once a certain boundary is crossed—and I’d argue that by the time a photographer is photographing his mother performing oral sex, that boundary is a long way in the rearview mirror—the parent-child aspect almost certainly has to be secondary.

“I don’t see this as a portrait of one woman’s eccentricity, but as a temporal mapping of reactions to realities in the world, psychological realities we carry with us from situation to situation, positions we must negotiate, subtexts we find ourselves living within.”

That’s from Ledare’s artist’s statement for a French exhibition of You Are Nothing to Me. You Are Like Air. It sounds like his MFA talking. But I think he’s also making a valid point, at least in terms of that project. I suspect most people, as they get older, have to come to terms with the fact that their life didn’t turn out as they’d thought it would.

At sixteen Tina Peterson saw an elegant future for herself. A future as a ballet artist, a performer of a classic form of dance. But she didn’t become the next Margot Fonteyn, or Gelsey Kirkland. She became instead a wife and a mother; she became a stripper and a credit card fraud (she charged nearly US$50,000 on her other son’s credit cards, and claimed the items were all gifts from male admirers). I suspect she became a rather sad woman who still sought ways to be seen as an artist and a performer. A woman who still sought ways to be viewed as attractive and desirable.

And she found them. As Ledare suggests, the map of Tina Peterson’s life has been shaped by the way she’s responded to her life situation. Those responses may not be conventional–or even rational–but at some level they’re understandable. The circumstance changes, the role she adopts changes. The same is true of Ledare’s responses to his life situation. When his mother played the role of aging sex bunny, he recorded it. When she began to play the role of martyr to her age, he recorded that.

I can say without hesitation that I dislike Ledare’s early, sexualized photographs of his mother—not because they’re of his mother, but because I find them uninteresting. I can also say I very much like his later portraits of his mother as victim. There is a sort of dignity there that I find very compelling. And that dignity is made all the more powerful because of the existence of those earlier tawdry images.

Is Tina Peterson simply assuming another role in the later photographs? Maybe. Probably. Almost certainly. But her life appears to be made up of roles she inhabits—and inhabits passionately—for a short while.

I began this salon by saying I didn’t quite know what to make of Leigh Ledare or his work. I still feel that way. Based on the later photographs of his mother, I want to give him the benefit of the doubt. In order to do that, though, I have to be willing to accept that when he photographed his mother masturbating or having sex with a young boyfriend, Ledare was documenting a performance by a creative woman assuming a temporary role. Ledare may have actually been able to separate his mother from the performer. But I find it very, very difficult to do that.

Life is complicated. People are complicated. Art is complicated. It seems to me that this one thing ought to be simple: you don’t photograph your mother having sex. Even if you’re both playing a role. It ought to be simple. Apparently it’s not.