Facts in isolation are never enough. John Gutmann was born in Breslau, Germany in 1905. That, in itself, means nothing. Add to that simple fact that Gutmann was the only son of a prosperous Jewish family, and it begins to mean something. Consider that 5% of the population of Breslau was Jewish and that it was an important center of Jewish culture and intellectualism, and it begins to mean still more. Now consider that in 1923, the year Gutmann graduated from the Johannes Gymnasium–an arts and humanities-oriented school–there were a series of anti-semitic riots in Breslau and you begin to see the social forces that shaped the man’s life.

Despite the political atmosphere in Breslau, Gutmann and his family remained there. He attended the Staatliche Akademie fur Kunst und Kunstgewerbe from 1923 to 1927, where he studied painting under instructors that included artists like the Expressionist Otto Mueller. He graduated with distinction, earning a degree that included certification to teach art in any State school in Germany.

Another fact in isolation: Gutmann moved to Berlin following his graduation. Nothing remarkable in that, until you consider that in 1927 Berlin was at the heart of one of the most transformative cultural movements in modern history. Radical leaps in science, in art, in philosophy, in music, in literature, in architecture, in cinema–these were all taking place in Berlin in the 1920s. Albert Einstein was the Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics; Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill began collaborating the same year Gutmann arrived in Berlin; Fritz Land released the movie Metropolis that same year as well; writer Christopher Isherwood began writing a series of ‘Berlin Stories’ that inspired a play called I am a Camera (the title was taken from the first line of one of the stories: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.”) which was later turned into a stage musical called Cabaret, which eventually became a movie of the same name.

What young man with artistic yearnings would not want to be in Berlin in 1927? John Gutmann moved there–and the city swallowed him whole.

He was, after all, a nice young Jewish boy from Breslau. He got a job teaching art. When he wasn’t working, Gutmann made paintings and sketches of cabaret culture. He was particularly intrigued by Amerikanismus–American popular culture. His work often involved erotic images of what he called “Negro jazz musicians” as well as cabaret dancers and gangsters. His work, however, wasn’t quite adventurous enough for the time and place, and it was largely ignored. In all likelihood, Gutmann and his work would have continued to be ignored, except for the reality of the aphorism that says desperate times call for desperate measures.

And by the early 1930s, times were truly becoming desperate for Jews in Germany. Gutmann’s family abandoned Breslau and emigrated to New York. Gutmann remained in Berlin but was unable to continue teaching because of new legislation passed by the National Socialist (Nazi) party forbidding non-Aryans from holding teaching positions. He found himself searching for a way out of the Germany–indeed, out of Europe altogether. His plan: buy a camera.

Gutmann had, over the preceding decade, watched as photography became a staple of newspaper and magazine reportage. He had seen an advertisement by Rolleiflex describing the simplicity of the camera, and felt confident that with his training in visual arts he should be able to easily master the machine. In 1933 he bought a Rolleiflex, shot three rolls of film, and presented himself at the Berlin office of Presse-Photo. He informed them he was a photographer who was about to embark on an international journey and was seeking an agency to market the photographs he would take along the way.

It was astonishingly presumptuous. Or innocent. In any event, it worked. Presse-Photo actually signed him, giving him a written contract that would enable him to obtain a press pass wherever he went. Where he went was San Francisco, California.

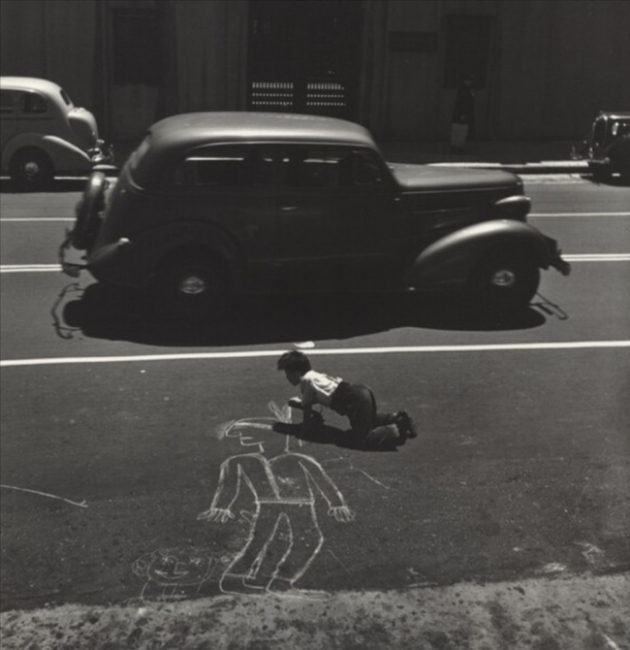

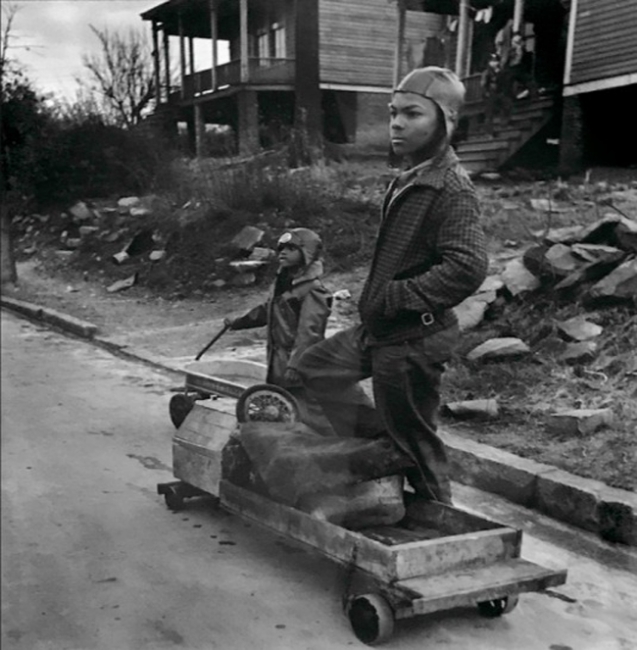

Gutmann arrived in San Francisco on New Year’s Eve, the last day of 1933. Within a short time he’d joined the California Camera Club (primarily to gain access to their darkroom and to meet people who could teach him how to develop his own film and make his own prints). His fascination with Americanism grew and he began to photograph American culture. In May of 1934, five months after his arrival, he sent off 165 negatives to the Presse-Photo agency in Berlin. In an accompanying letter he described the amazing diversity of people in San Francisco–Germans, Italians, Canadians, Jews, Chinese, Mexicans, Greeks, Japanese, Irish, all living in relative harmony (although, he noted, he was disappointed to see that the friendly hospitality didn’t appear to extend to “Negroes, whose numbers in the aggregate are small.”).

The negatives Gutmann sent reflected that diversity. Unfortunately, photos of happy groups of mixed nationalities were of little use to a photo agency located in a nation where Jews were now prohibited from sitting on public benches. Few of those 165 images were sold.

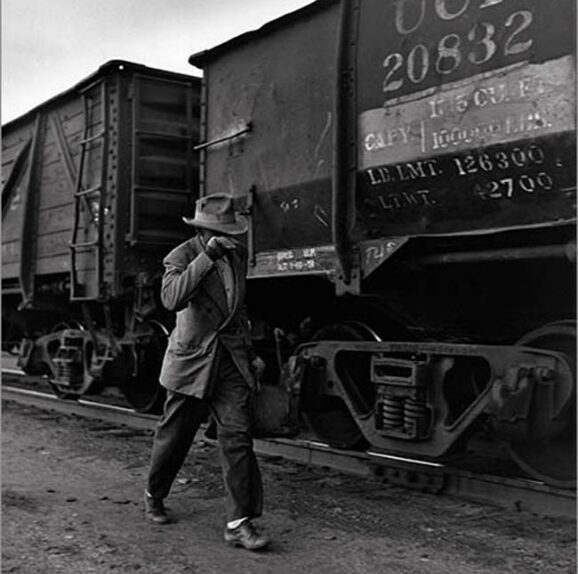

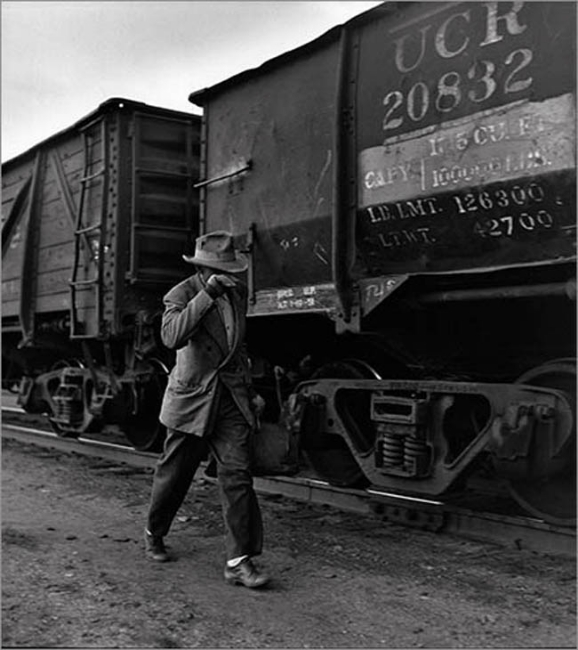

Gutmann began to study the photographs that appeared in the local newspapers. He decided that instead of sending Presse-Photo random images of American culture, he’d give them photo-stories–images that were related and linked by a theme or event. He photographed a dockworker’s strike, he photographed the ways unemployed people (this was the era of the Great Depression, after all) amused themselves, he photographed African-American nuns–and he sent all the worthy negatives to Presse-Photo, who bought a very few images each time.

The photographs they bought were often published without credit given to Gutmann. On those occasions when he was credited with the photo, they sometimes ‘Aryanized’ his name, calling him Goodie. In Presse-Photo’s defense, if they’d actively promoted the work of a Jewish photographer they might have faced some sort of repercussions–and repercussions from the Nazis were serious repercussions. After two years, Gutmann severed his relationship with Presse-Photo.

While he now identified himself as a photographer, Gutmann still considered himself an artist. His art, however, was painting and drawing–not photography. It was his painting (and his degree in art) that landed him a job teaching art at San Francisco State College. Still, he kept shooting photos, hoping to someday make a living at it. He entered contests for the prize money, he found a new agency that would pay him US$10 per photo, he managed to get a couple of gallery shows. But it was his teacher’s salary that kept him solvent.

Gutmann couldn’t be considered poor, but he was struggling financially. This was his life until 1942. That year, a few months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, John Gutmann, at age 37, joined the U.S. Army.

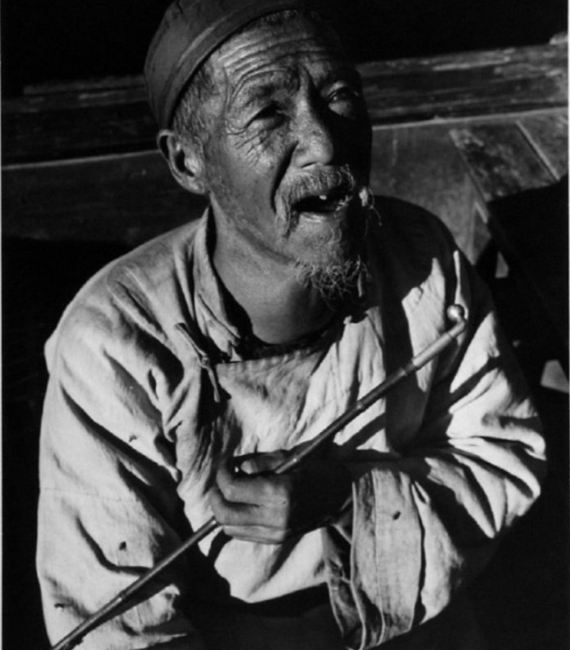

Not surprisingly, his first military assignment was as a photographer for the base newspaper. With it came his first major breakthrough as a professional photographer: a full page spread in Life magazine. Gutmann was eventually assigned to the Office of War Information and sent to the Asian Theater. He spent the war in India, Burma, and China. When he wasn’t shooting photographs for the military, he was shooting them for himself.

Like most U.S. military volunteers of that era, Gutmann had signed up for the duration of the war. He remained on active duty until the war ended in 1945. He then returned to San Francisco, where he resumed his careers of teaching and freelance photography–but with significantly different results.

After the war Gutmann’s life finally began to come together. He started a creative photography program at San Francisco State College. Some of his Asian photographs were featured in National Geographic Magazine. He submitted work for review at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. He was a regular contributor to the Saturday Evening Post.

Gutmann continued to work until the early 1970s, when he retired from photography. Though he never achieved great success, he did manage to garner some modest attention. A few art scholars have examined and critiqued his work, but he remains somewhat obscure. Said one scholar, “Photographic history has found no name-tag for Gutmann–he himself prefers to be linked with the ‘unclassifiables.’” He is sometimes said to foreshadow more modern photographers, and sometimes said to echo the work of earlier photographers–but Gutmann’s work appears to occupy a place that scholars find undefinable.

To me, John Gutmann seems like a nice guy who only wanted to give people what they wanted–but never entirely understood what that was. In Berlin his work wasn’t quite avant-garde enough; when he found his way to the U.S. his work was seen as too celebratory of American culture to please his German agency; when he left that agency, he was too artistic to be commercial and too commercial to be artistic. He was like an actor who wasn’t quite good enough to be a film star, but was still too good to give up the stage.

Most of us would consider that success, especially considering he bought his first camera primarily as a ploy to escape the country of his birth.

I began this Salon by saying facts in isolation are never enough. Here’s another fact in isolation: John Gutmann died in 1998 without ever achieving fame or fortune. Facts in isolation are never enough. John Gutmann died in 1998 having achieved a solid, interesting, varied, consistently engaging body of work. Ain’t nothing wrong with that.