In my morning news-reader today was an article headlined Probing Question: Are Smartphones Changing Photography? The lede is:

Although cell phone cameras are a recent innovation, they continue nearly 150 years of tradition that photography should be broadly accessible and an extension of our own experience.

I suspect Mishka Henner would agree with that lede — although not in the way the article intends. The notion behind the article appears to be that the ubiquity of cellular photography is really just an extension of the work begun by George Eastman and the introduction of the Brownie camera, which brought photography to the masses. The reporter’s answer to the question of whether smartphones are changing photography appears to be ‘no’. But let’s face it, the reporter wasn’t really attempting to address the question. The reporter was merely trying to fill a 700 world hole in the morning news. The article ends with this:

Ultimately, it’s not the lens or the camera that creates the image. It’s the person behind the lens.

Henner, I think, would absolutely agree that photography should be (and is) broadly accessible. I think he might also agree that it should be ‘an extension of our own experience.’ But where I believe Henner would disagree is that he makes a distinction between the act of photography and the consumption of photography. It’s no longer necessary to have a person behind the lens. But it’s still necessary for the image, if it’s to have any meaning whatsoever, to be viewed.

In the days of Eastman Kodak’s Brownie camera, we suddenly had tens of thousands of budding photographers whose images were seen by relatively few people. The audience – mostly family and friends – was limited by the fact that the image was physical and could only be seen by people who were in the same location as the print. Smartphone photography has broadened the pool of photographers to thousands of millions. The audience for those most of those photographers remains primarily family and friends; on average, there’s probably been only a slight increase in the number of people who view these photographs. However, because the images are digitalized and because of the creation of the Internet, those photos are now accessible to thousands of millions.

What’s been missing from the discussion are those multiple millions of photographs being made by self-activated robotic photographers – photographs that for the most part are being automatically archived without being seen by anybody. Henner is bringing those images to an audience. Not the intended audience of technicians, but an audience of art lovers.

These photos are, as the reporter in the article suggests, broadly accessible. But while the photographs themselves may not be ‘an extension of our own experience’, the consumption of them – the choice of individual images, the framing of the images, and the presentation of them – is most certainly an extension of our own experience.

When asked if these photographs constitute ‘real photography’, Henner responded:

“I just think that people hang on too heavily to categories and ideas about what’s acceptable. I’m working with images of the world, that’s it. Whether a robot’s taken them, or a human being, the point is it almost doesn’t matter anymore.”

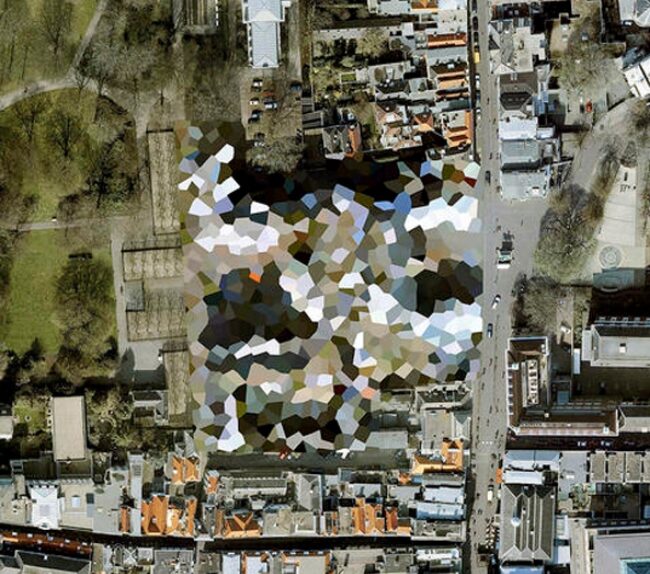

In 2011 Henner released a series entitled Dutch Landscapes. As you might guess, these aren’t traditional landscapes. They’re satellite images. Google had introduced is free satellite imagery service six years earlier, creating a problem for governments worldwide. There are places on this planet that governments don’t want visible. For the most part, governments have responded to Google’s satellite imagery by blurring out sensitive and secure locations. The practice of blurring doesn’t hide the locations; it simply obscures them.

The Dutch government took a different approach. They applied bold, multi-colored, pattern-disrupting polygons to cloak the areas. Henner was intrigued by the contradictory absurdity of creating a highly visible, attention-drawing graphic style to censor sensitive governmental sites meant to be hidden. He’s chosen to interpret this as a modern form of landscape art.

“In its raw form, satellite imagery can be quite dull,” Henner says. “Cropping, adjusting, and forming a body of work out of them completely transforms these images into something that can be beautiful, terrifying and also insightful.” The power of traditional landscape photography is grounded in the viewer’s contemplation of what is visible; with Henner’s Dutch Landscapes the power is derived from the contemplation of what is deliberately not visible.

Again, the imagery itself is non-political and non-ideological. By simply isolating geographic locations meant to be hidden, Henner introduces a political and ideological perspective – but that perspective resides in the viewer. Not in the image, not in Henner, but in the viewer. The point of view of the individual consuming the image determines how it is interpreted.

That’s not quite the case with Henner’s Beef and Oil. This series focuses on the two largest commodities produced in the United States. Again, Henner has appropriated carefully selected and cropped satellite imagery. Although the images are offered without comment (other than information identifying the locations), they are both beautiful and disturbing. The stark colors, the well-defined geometric shapes, the initial confusion in regard to size and scale –taken in combination, these create very striking and compelling images.

The viewer doesn’t need to be aware of the fact that 35% of U.S. farms are purely devoted to raising cattle for beef, or that the U.S. exports nearly three billion pounds of beef yearly, bringing in more that US$5 billion. The viewer doesn’t need to know that the U.S. consumes around 19 million barrels of oil each day, or that the U.S. accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s oil consumption. The viewer doesn’t have to understand that the reddish-brown ‘lake’ seen in one of the images is actually a massive cesspit for cattle waste. Simply by looking at these photographs it’s clear that some non-organic force is shaping the landscape and doing it on a massive scale that’s visible from space.

Henner may display the images without comment, but he’s well aware that critics will make up for that absence. The tension that arises between the disinterested camera and the human imperative to create meaning is the driving force that turns satellite imagery into a powerful political comment. That’s the heart of the project.

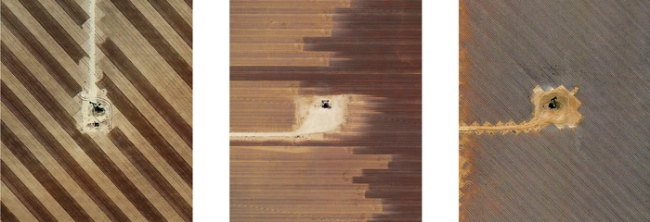

Henner continued his examination of the U.S. oil industry in a series called Pumped. In this series, he reveals isolated pumpjacks centered in a variety of beautifully textured and geometrically pleasing landscapes. The images are, for the most part, visually attractive. It’s only when the viewer realizes the blot in the middle of the image is an active oil pump that the ugly reality intrudes. It’s like looking at a lovely face and realizing what you thought was a beauty mark is, in fact, a pimple. Or a collection of cancerous cells.

What Mishka Henner actually does isn’t controversial. He simply takes existing satellite imagery and displays it for public consumption. What Henner shows, however, is most certainly controversial — because he shows aspects of the world many of us don’t really want to see, aspects we may not want to know about, aspects of the world governments would prefer to remain hidden. This, of course, is one of the purposes of documentary photography.

A decade ago, if you’ll recall from the previous Sunday Salon, Mishka Henner attended an exhibition of documentary photography at the Tate. That exhibit was devoted to “the quiet documentation of overlooked aspects of our world, whether architecture, objects, places or people.” In a very real sense, Mishka Henner is still engaged in that quiet documentation.