There are lives that seem more like works of fiction. Photographer Adolfo Kaminsky, who died last week at the age of 97, had one of those lives. In fact, a rather large chunk of his life revolved around fiction. Adolfo Kaminsky was also known as the King of Forgeries.

He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1925 to a Russian-Jewish family. The family moved to France in 1932, when Kaminsky was seven; first to Paris, then to the small town of Vire in Normandy. He was still a child when he went to work in a dye shop, where he became interested in the chemistry of color. Kaminsky was only 14 years old when the Second World War began in Europe. His family was eventually sent to the Drancy internment camp near Paris, where French Jews were housed until they could be transported to the work or death camps. His mother died while being transported, but a clerical error on a document resulted in Kaminsky and his father being released.

“When we were released from Drancy, I wanted to stay in the camp with the others who were slated for transport, out of solidarity. My father said: ‘No, there are more important things you can do on the outside.’ He had no idea what my job would be within a few weeks.”

Because of his experience in the dye shop, Kaminsky was soon recruited by the underground French Resistance movement to help forge documents. His first assignment was to forge his own identity card. He quickly found himself producing not only false documents (ID cards, passports, food ration booklets, train tickets) but also the various stamps necessary to create the appearance of an authentic document. This was where Kaminsky learned photography.

Kaminsky became the best and most efficient forger in the Resistance. He eventually created a secret laboratory in Paris where he and his team worked tirelessly to produce forged documents. They operated around the clock. “Keep awake. The longer possible. Struggle against sleep. The calculation is easy. In one hour, we make 30 false papers. If we sleep one hour, 30 people will die.” It’s estimated his forgeries saved around 14,000 lives by enabling Jews to either flee or to live undetected in Nazi-controlled territories.

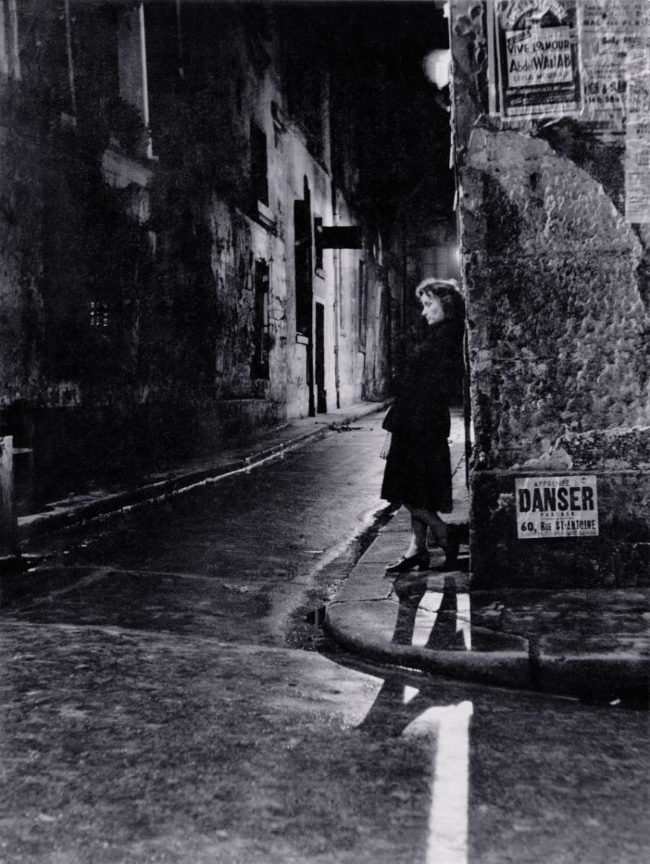

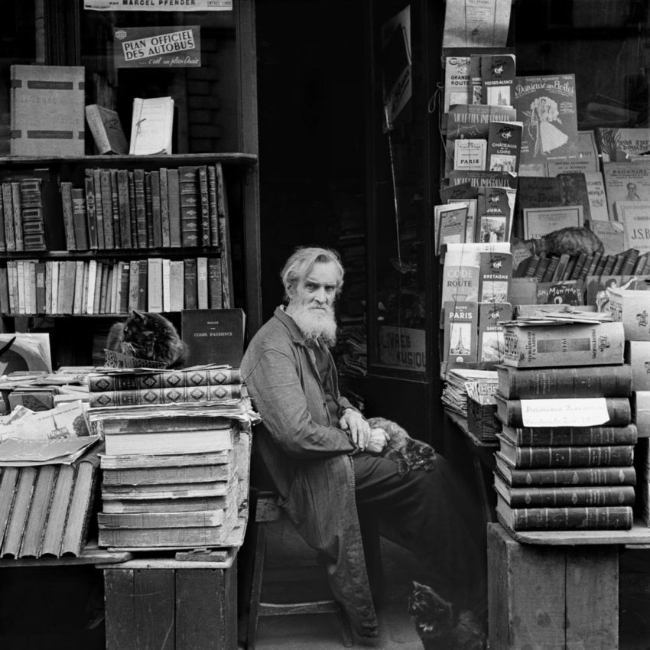

At the end of the war, Kaminsky bought a Rolleiflex camera and began to use his photographic skills to document life in Paris and elsewhere.

“All my friends had left and, to overcome loneliness, I plunged body and soul into photography.”

He seemed drawn to ordinary people trying to lead ordinary lives. Street musicians, booksellers, knife-grinders, flea-market merchants, ticket punchers, couples walking together—people just trying to get by in life. There is a sort of casual grace to these photos, a sense that he saw something in his subjects that they weren’t aware of themselves.

But his skills as a forger were still highly sought after. At the end of the war, there were hundreds of thousands of Jews and other victims of Nazi oppression who’d managed to survive. Some had been liberated from concentration camps, others had been living in hiding. They all wanted to go back to their homes and families, but many of them discovered they had no family left, no home to return to; many of their homes had been destroyed or claimed by others, some entire villages and towns simply didn’t exist anymore. These survivors were ‘temporarily’ placed in Displaced Persons camps.

Kaminsky was approached by groups wanting to escape to Palestine.

“I was not a Zionist, but I defended firmly the idea that every person, particularly if his life was in danger, has the right to move freely, cross borders and choose his place of exile. Those Jews who wanted to get to Palestine were mostly on the left side of the political map and had nowhere to go. They did not want to return to Germany or Poland and had no wish to settle in France. They needed help in leaving Europe, and I did everything I could.”

He continued to provide forged documents to resistance and revolutionary groups for the next thirty years. Anti-Franco groups in Spain, freedom fighters in Angola, revolutionaries in South America, opponents of the regime in Greece, the FLN during the Algerian war, American military deserters during the Vietnam war, anti-apartheid activists in South Africa, the revolutionaries of the Prague Spring movement.

Kaminsky never provided forgeries for money. He acted entirely on the moral principles he developed through experience. His reputation as King of Forgeries was well-known in revolutionary circles, but obviously he remained silent in public about his work. He began to discuss his career as a forgery master only after his youngest daughter, Sarah, learned of it and started asking questions. She has since written a book about her father: Adolfo Kaminsky: A Forger’s Life.

In recent years, the French government has recognized the contributions of Adolfo Kaminsky; he’s been awarded the Croix du Combattant, the Croix du combattant volontaire de la Résistance, and the Médaille de Vermeil de la ville de Paris for his actions during the Resistance.

Throughout his life, Kaminsky demonstrated a passion for helping ordinary people who simply wanted to control their own lives. We may not always agree with his choices, but we can see his love for people in his photography. More importantly, we see it in the way he lived all 97 years of his life.