It’s a strange thing to do, when you think about it–using a large format camera to shoot relatively formal portraits of casual strangers in nondescript settings. Yet that’s what Rineke Dijkstra has done for the last decade and a half. And she does it so very well it’s made her an internationally-known portraitist.

Dijkstra was born in Sittard, Netherlands in 1959. Like so many Dutch artists, she seems to have a natural affinity for delicate light. She went to school to become an arts and crafts teacher but apparently didn’t find it particularly interesting. After a friend loaned her his camera, Dijkstra experienced one of those classic this is it moments. She abandoned her plan to be a teacher and enrolled in a photography program at Gerrit Rietveld Akademie in Amsterdam. She was 19 years old.

After graduating, Dijkstra went to work as a freelance photographer, getting small gigs shooting corporate portraits for magazines and newspapers. Although she didn’t find the work fulfilling she says she “learnt a lot about how to be technical, how to work with people and how to work fast.” It may not have been glamorous, but she was making a living as a photographer.

Then she broke her hip.

Part of Djikstra’s rehabilitation process involved physiotherapy in a swimming pool. She started taking self-portraits after her sessions. That sparked a desire in her to photograph something different, “something that was miles away from the boring and predictable businessmen I had until then mostly photographed.” She toted her 4×5 camera out to the beach and began to take the first photographs for a series that would eventually bring her international praise. The Beaches series would, over the course of a decade, take her from the Netherlands to Belgium, the U.S., Poland, Ukraine and Gabon.

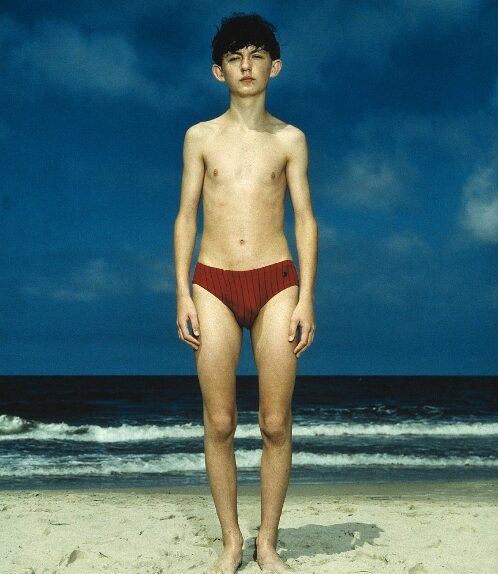

With her Beaches series Dijkstra developed the aesthetic that’s permeated virtually all her subsequent work. The composition is simple, balanced, minimalist and formal. Her subject is positioned in the center of the frame, generally caught in an uncertain moment somewhere between unposed and posed, most often looking directly at the camera. She usually combines natural light with a single Lumedyne flash unit to fill in shadows.

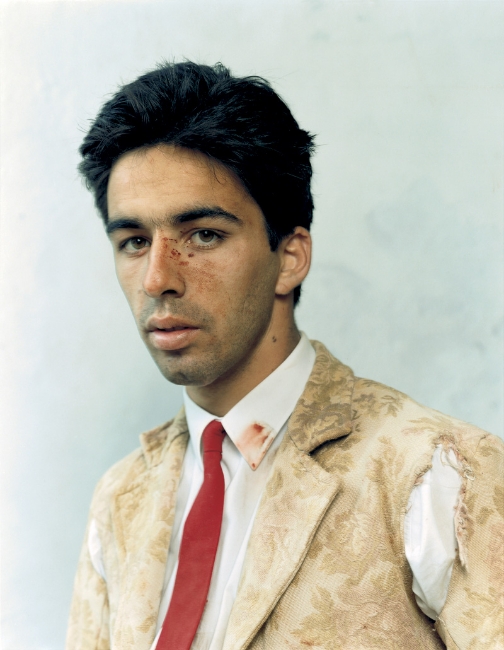

Dijkstra’s subjects are most often people in some transitional state. Adolescents hovering between childhood and adulthood; women within a day of having given birth, dealing with the reality of being a new mother; matadors immediately after they’ve left the bullring; young men and women in the process of being turned into soldiers.

As simple as they look on first glance, these portraits lend themselves to a very detailed level of study. By removing the subject from almost all overt contextual clues–location, culture, community, etc.–Dijkstra emphasizes details that the viewer might otherwise fail to notice. The size of her prints–they are very nearly life-sized–makes that sort of scrutiny possible. “For me,” Dijkstra says, “it’s important that if you stand in front of my picture, you feel the urge to come closer.” Her approach apparently works; one critic commented “I can’t remember a show where the audience stood for so long in front of a series of images of ordinary people.”

Because the images–and most especially the Beaches series–are so similar in composition, there is nothing to distract the viewer from studying the subjects. In the photograph above, for example, we are painfully aware of the boy’s uncertainty and anxiety–and his male need to not to show uncertainty and anxiety. He stands stiffly, awkwardly, but straightforward, almost at attention. He’s clearly not quite comfortable in his boyish body. He is, like so many young people, a mass of contradictions. The dark, threatening background makes his awkwardness seem almost defiant and courageous.

“I try to look for an uninhibited moment, where people forget about trying to control the image of themselves. People go into a sort of trance because so much concentration is needed from both photographer and the subject when you’re working with a 4×5.”

It could be argued that Dijkstra engages in a sort of ‘gotcha’ photography, waiting behind her camera for an unguarded moment when the subject discloses something about herself without intending to. Yet those moments also humanize the subject; they reveal the subject as an individual.

In the mid-90s Dijkstra turned her camera on new mothers. She photographed three women after they’d given birth. One was photographed an hour after giving birth, another photographed one day afterwards, and the third one week later. The aesthetic is the same: a single subject centered in a neutral frame. Here, though, Dijkstra is depicting the organic reality of birthing. Traditionally, art has treated the birth process with more sympathy and adoration than honesty. Dijkstra shows the effects of pregnancy and birth on the body. She does it with empathy and restrained affection, but with a frank and candid eye. Pregnancy and birth aren’t easy on the body. The beauty of motherhood is there, but it’s not glamorized.

The same year she photographed the new mothers, Dijkstra also shot a series of portraits of young Portuguese matadors. It should be noted that traditional Portuguese bullfighting is different from the Spanish style with which most people are familiar. The bull is provoked and bloodied in much the same way, but the matadors face the bull without either cape or weapon. They physically seize hold of the bull by the head, after which others assist to subdue the bull. The matador portraits were taken immediately after they left the bullring.

“The matadors came out covered in blood and exhausted, very similar to the mothers. I didn’t intend to do the men like that—all macho and the women as mothers—it just evolved from the experience.”

In a way, these two series support each other; in a way both of these series of portraits honestly address gender roles–and in a way they reinforce stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. It’s not surprising these two series are often displayed together.

Each of these series suggests a universal reality, one we can all relate to even if we haven’t given birth, even if we haven’t faced a bull in a bullring. We have all experienced transformative moments, we’ve all gone through difficult situations from which we’ve emerged exhausted, but with the feeling that we’ve accomplished something–or at least survived it.

It can be difficult to warm to Dijkstra’s portraiture. The surface ordinariness of the images and the simplicity of her compositional style can be off-putting, especially in an era that celebrates brashness. There is no flashiness about her work, nothing overtly controversial, nothing deliberately provocative. Instead, she has consciously made an effort to keep her work clinically uncomplicated.

For all its simplicity, there is something very adult about these images. There is no nonsense here. The images are well-balanced, nuanced, sophisticated without being elitist, and extraordinarily accessible. Accessible, but not necessarily comprehensible.

There is no noise in Dijkstra’s work. In early radio technology, signals were evaluated on two five-point scales: clarity and strength. An exceptionally strong signal heard with precise clarity was said to be received “five by five” (a phrase probably familiar to fans of Buffy the Vampire Slayer). That phrase applies perfectly to Dijkstra’s portraiture. Her photographs are strong and clear; they say exactly what she means to say without being diluted by extraneous details.

And what does Rineke Dijkstra mean to say?

“For me it is essential to understand that everyone is alone. Not in the sense of loneliness, but rather in the sense that no one can completely understand someone else.”

As we look at the people in these photographs, we intuitively understand we can never fully comprehend their experience, but we can find some way relate their experience to our own. These people, as Dijkstra demonstrates, are not that different from us.