Some photographers have an agenda. They see photography less as a form of expression and more as a tool for bringing public awareness to their cause. Their photography is not intended to please, but to inform; not meant to form an aesthetic, but to form an opinion. One such photographer was Lewis Wickes Hine.

Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin in 1874, Hine was forced to help support his family after his father died in an accident. His first job was at a furniture upholstery factory, where he worked 13 hours a day, 6 days a week, earning US$4 per week. He began to attend university extension courses and eventually became a teacher. In 1901, he was hired by the Ethical Culture School in New York City, which catered to recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. In addition to his teaching duties, Hine was asked to be the school’s photographer.

By 1903, Hine bought his own camera, apparently with the intention to use it as an instrument of social awareness and change. His first photographic project grew out his concern for the living conditions of newly-arrived immigrants in New York. In order to understand the immigrant experience, he began by turning his camera on the men and women arriving at Ellis Island, the gateway for nearly all immigrants coming from Europe. He documented them from their arrival to their first homes in the ghettos, slums and tenements of the Lower East Side.

As he studied the new immigrants, Hine also became interested the other poor and working class residents of New York’s tenements. He was particularly affected by the young boys and girls who labored to help their parents survive, perhaps because of his own early experience.

In 1906 Hine began to do freelance photography for the National Child Labor Committee. He traveled the U.S. photographing children working in mills, sweatshops, coal mines, brothels, bowling alleys in an effort to promote child labor laws.

Hines kept detailed notes on the children he photographed, including comments they made as he interviewed them. The twelve year old boy in the photograph above was unable to read or write. He’d been employed by a textile mill in Columbia, South Carolina for four years, since the age of eight. He told Hines, “Yes, I want to learn, but can’t when I work all the time.”

Although Hine wasn’t interested in photography as an art, he broke with documentary conventions by telling his child subjects to look straight at the camera. He wanted the viewer to look the subject straight in the eye–an approach that was considered daring and confrontational, but was effective.

The photograph above of newsboy Tony Casale demonstrates the odd relationship between child workers, their parents and their employers. Casale had been selling newspapers in Hartford, Connecticut since age seven. He was often out selling papers until 10PM. The newspaper initially agreed to hire him because he would work for little money; they kept him on because his father would abuse him if he didn’t bring home enough money. The boy’s supervisor said he’d seen marks on Casale’s arm where his father had bitten him for not selling enough papers. Casale, speaking for himself and other newsboys, told Hine, “Drunken men say bad words to us.”

As his photographs attracted more attention, factory owners and sweatshop employers began to refuse to grant Hine access to their worksites. In response, he began hide his camera and photograph the working conditions of children surreptitiously. He sometimes gained entry by posing as a fire inspector or an agent of a licensing board. Hine also began giving public lectures on child labor. At one such lecture, when confronted by an audience member who complained of being tired of seeing the photographs of pathetic children, Hine responded:

“Perhaps you are weary of child labor pictures. Well, so are the rest of us, but we propose to make you and the whole country so sick and tired of the whole business that when the time for action comes, child labor pictures will be records of the past.”

Hine’s photographs of child laborers helped inspire the creation of the Children’s Bureau in 1912. It took another 26 years for the Fair Labor Standards Act to be enacted, which effectively ended unrestricted child labor in the US.

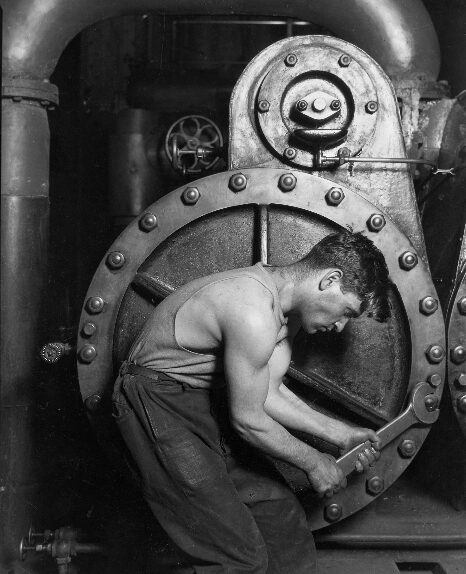

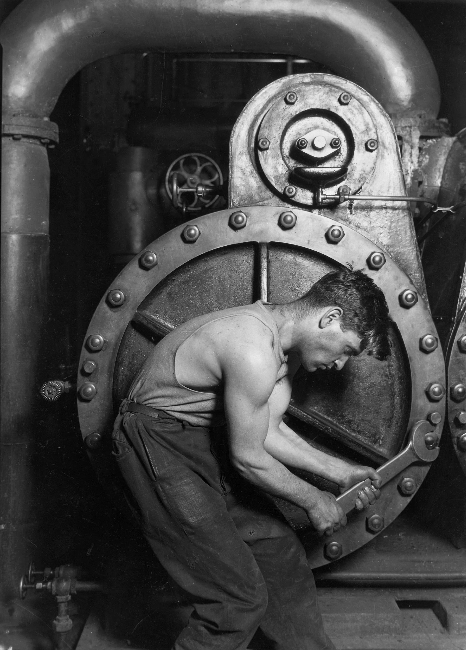

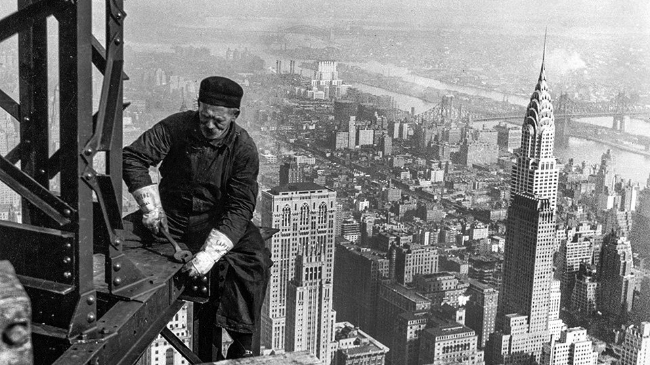

Each of Hine’s photographic projects seemed to lead to another. His interest in immigrants led him to study child labor, which led him to study the working classes in general. His photographs of working men and women led to the project that made him most famous. In 1930, at age 56, Hine was hired to document the construction of the Empire State Building. The photographs were published in a book (Men at Work) and given museum space in several cities throughout the U.S.

Hine spent the next several years exploring the complex relationship between humans and machinery. He celebrated the work and the beauty of the workers while at the same time he deplored the notion that workers were held in thrall to industrial machines.

Hine, for all his critical and political success, had also angered the great capitalists of the U.S. As a result, he had great difficulty actually earning money from his photography. In 1940, only eight years after his biggest success, Hine was made homeless by his inability to meet his house payments. He died ten months later in extreme poverty.